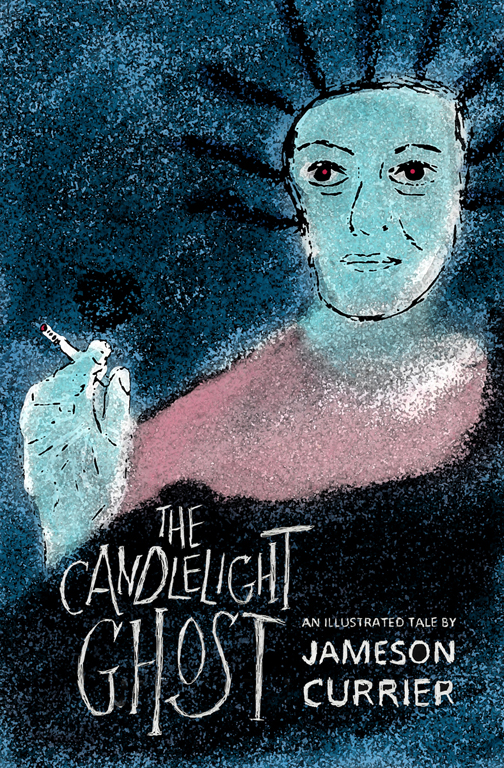

illustration by Jameson Currier

by Jameson Currier

All he wanted was to dance in a Broadway musical. And he had spent years taking lessons to train his body to do so: ballet, jazz, tap, voice, acting, and karate. When he was a child his mother made him costumes: a leprechaun, a cowboy, and once, even, a sequined jacket. By the time he was twenty-seven he had danced in four Broadway musicals—one, a revival, he had a featured solo in and toured with across the country. But it was off-off-Broadway that I first met Dennis; we were both appearing in a showcase of a new play. I was twenty-three and had just moved to New York City after graduating from college, trying to find myself a foothold in the theatre. Dennis was twenty-two and had finished appearing in his second Broadway musical. But what was notable about this production, besides introducing us, was that neither of us was required to sing or dance. We began as fully clothed characters who talked nonstop in foreign accents; by the end of the second act we were silent and had completely disrobed. Now, fourteen years later, pausing in front of a shelf of thick wool sweaters in a store that describes itself as the world’s largest, I am baffled by the paradox of the present, that Dennis has asked me, after all these years, the man who had the chance to admire his nude body close-up for a two-week run, to help him pick out a coat to protect him against the winter weather.

I have always thought Dennis was handsome, even now, though he is thinner than when he danced on Broadway. Until last spring he weighed 177 pounds, having built up his lissome frame in his early thirties by going to a gym. Now he lies and says he weighs 150. He is taller than me by two inches, five feet eleven, and he has light-olive skin and curly black hair, which he says his ancestors developed centuries ago in Greece. Yet, no matter how much or how little he has weighed, for as long as I have known him he has had a dancer’s grace and poise; as he unfolds a blue cable sweater a salesman has handed him and holds it up in front of his chest, I notice his feet are placed perfectly in third position.

I started dancing late in life, though I had developed good coordination from sports—tennis, swimming, basketball, and baseball—abstaining from any sort of dance training because of the stigma attached to it in my small Missouri hometown. It was Dennis who took me to my first dance class, a month after that off-off-Broadway play closed. I remember, as I climbed the stairs to a third-floor studio and changed into a dance belt, tights, and T-shirt, how self-conscious I felt about it all, as though someone would approach me at any moment and say, with a laugh, “What do you think you’re doing here?”

There were about twenty other men and women in this class, beginner’s jazz, which Dennis had assured me was the easiest one in which to learn the basic movements. I was relieved when I noticed that most of these other students looked like they had just walked out from behind a desk—secretaries, brokers, receptionists, and accountants—though I could tell by their determined expressions, the steady concentration behind their eyes, that they dreamed of being actors or dancers. The teacher, a man wearing a scoop nylon shirt and a bandanna around his forehead, was a friend of Dennis’, and together they led the group through a series of stretches and simple movements of body parts I would never have done alone, at home, in front of a mirror. But there, dwarfed in a cavernous room of arched windows overlooking the grimy buildings of Times Square, standing between these other nondancers, I didn’t find the movements so awkward or suggestive. After all, I thought, I am merely an actor trying to master another facet of his craft. Toward the end of the hour we did leaps diagonally, one at a time, across the room, then advanced to what was described as a pirouette, but what I discovered instead was a dizzy twirl, and finally a combination exercise of steps and lunges which we all tried to perform. I went back to the class several times, because I decided the conditioning was good, toning unused muscles of my body. Dennis was always there, and though I was never certain, I suspected that he and the teacher saw each other out of the classroom as well.

Dennis’ strength was ballet, though he decided early on he would concentrate on jazz and tap, the road which at that time led to Broadway. Though his technique and training greatly surpassed mine, he would often stay after class and show me other steps. He would begin my tuition with the rigidity of an elderly ballet master, although, when I feigned awkwardness, my way of garnering more attention from him, he would become extraordinarily transformed into an eager boy showing a set of tricks to another. I watched him float through arabesques, glissades, brisés, and cabrioles while he showed me how to hold my arms, align my posture, and place my feet. Once, when I asked him to critique my series of jetés, he laughed and said, “You look as stiff as the marching brooms in Fantasia.”

Since the day I first met Dennis he possessed a set of characteristics I admired and tried for years to perfect: a beautiful body; a calm, sensitive disposition; a gracious, congenial personality; and a sense of humor which could leap spontaneously between slapstick and a clever, dry wit. Though he looked as a dancer should—long graceful legs and lean willowy arms connecting to a slender frame at sharp, tight joints—he was not narcissistic, as dancers often are. He was raised in Connecticut, by parents who, he said, made sure he was well mannered and educated, and who brought him into the city for lessons and shows, recognizing his talent and passion to dance at an early age. In fact, I envied him, not only on account of his good looks and commendable qualities, but because he always knew what he wanted and where he was headed. I have always been impatient, easily distracted, and try to avoid making any decisions at all. Often, I jump between an infatuation and a distaste for the theatre, racing to auditions only at the last possible moment.

Watching him now, as we ride the escalator up to the second floor of the department store, his hand placed against the rail as though he is about to begin a plié, I realize his decisions, his choices, his future were always directed by his body. On those days I watched him demonstrate a pirouette for me, he seemed exceedingly ethereal, as though unaware of the way women and men stared at him, some approaching with hope, wishing to charm and seduce him into their lives. Though he told me right off he had a preference for men, he detested the tiny, smoky bars of the Village and the trendy, crowded discos renovated from unused theatres and warehouses, places which never failed to lure and enchant me. I went to these places in search of attention and camaraderie. Later, as I became more addicted to Manhattan nightlife, I realized I used them as avenues for possible sex. Dennis had no such need for these places; as long as I have known him, he has never been at a loss for companions.

Dennis’ first boyfriend I remember was the one who attended that off-off-Broadway play. His name was Brad or Chad or Tad or something like that, and I met him backstage in the small curtained space Dennis and I shared as a dressing room. I could tell Tad was the jealous type; he was extremely suspicious of me, and he stood with his fists clenched at his side next to Dennis, who was seated in front of a mirror, and began explaining why he didn’t like the play, why he thought it was the wrong career move, why he felt Dennis should quit the production. Dennis’ reactions were polite and controlled. Tad began working himself into a state near hysterics and I could feel him nervously glancing in my direction, willing me to leave before his anger erupted and he started a fight. The one time I looked at the two of them, Tad was holding Dennis’ shirt with both hands, and I noticed Tad’s face had become red and his eyes were wide and almost popping out of his skull. By the end of the run, Tad was gone, never to be seen again.

There were others, too: a television writer, a travel agent, a paramedic, a Brazilian financial analyst, a fashion designer’s assistant, and several actors and dancers, though Dennis often told me he preferred not to get involved with someone in the same profession as himself. And there was a period when I didn’t see or hear much from him. He was touring across the country in a revival of a Broadway musical, though I remember he once called from Oklahoma City and left a message on my answering machine. He said as quickly as he could that he hated the production, he hated traveling, and he hated the company, though he was having an affair with the stage manager, but anticipated it would end by the time they reached Houston. When I replayed the message, there was no number left so I could call him back.

It was almost a year later when I ran into Dennis by chance on Columbus Avenue and met his new lover, Joel, a tall, attractive man with a bewitching smile and a repartee of double-entendres that kept Dennis grinning. Joel was about five years older than Dennis, and neither an actor nor a dancer but a lawyer who worked for legal-aid cases for the city. Dennis began calling me again shortly after our accidental meeting; Joel did not share his fondness for movies and needed to spend most of his free time researching cases. Joel was a workaholic and clearly not as possessive of Dennis as his previous lovers had been, which left Dennis and I plenty of time to rekindle our friendship by going together to the cinemas around Times Square. I remember, the first few times I met Dennis at Joel’s West End Avenue apartment where Dennis had moved, how uncomfortable I was while Joel was around; my comments were stilted and simple, as though I were talking to a parent. Joel did his best to put me at ease with an amusing remark, whispering mischievous asides to me in a boyish manner when Dennis was distracted or out of sight. After I got to know Joel better, I realized he respected the time Dennis and I spent together. He trusted Dennis as much as he trusted himself, and, in a somewhat ironic parental fashion, entrusted me with bringing Dennis safely back.

When we reach the coat department on the second floor I ask Dennis, “Want me to pick one out for you?”

Dennis slips easily out of his jacket. “No,” he answers matter-of-factly. “You have lousy taste.”

* * *

Often the men I would meet and bring home from the bars or the gym were more stunning than the ones who latched on to Dennis. I have always been captivated by the beauty the male body could attain, perhaps the main reason I was first drawn to Dennis. That Dennis and I were never lovers, not even for a night, was not a mystery to either of us. Though I knew he was attracted to me, a fact I was intended to overhear when he announced it in a loud whisper to the director of that off-off-Broadway play, Dennis was the sort of guy who wanted a relationship with only one man at a time. I was more restless and adventurous. One night, backstage, I asked Dennis if he wanted to go out for a drink. “Only a drink,” he answered. “Nothing else. I know your type. Who wants to wake up with a broken heart?” For years he would tease me about what he considered my major flaw: “Why is it that someone good looking and smart still thinks with the wrong head?”

Sometimes Dennis would ask for details of my encounters with other men, beginning with the opening lines of our introductions. And usually I would classify my experiences for him, whether the sex was good, average, awful, or incredible. And there was always some moment with a man which stuck in my mind, like a song you hear on the radio and like but of which you can only remember a hook or a phrase. And when I described this for Dennis, the way one man’s buttocks were tight but pliable like firmly blown balloons, or the way my fingers fit perfectly between the oblique muscles of another man’s chest, he would become still and silent, his breathing short and heavy, as though enrapt in the viewing of a porno movie.

Since living with Joel, Dennis had never been unfaithful, nor, I imagined, had the desire to be crossed his mind. Joel had started spending more time with Dennis as his career became more prosperous and secure. Together they took trips to Mexico, Brazil, and Europe, redecorated their apartment, and began to arrange dinner parties. Often, on the nights when I would talk with them in their kitchen as they prepared an elaborate menu, I marveled at how they now fully complemented each other: one concentrating on the meat, the other on the salad, yet both of them alternating chopping onions, shredding carrots, peeling potatoes, or embellishing each other’s remarks with specific details. I couldn’t help being envious of their relationship, begun, as Dennis once told me, the same casual way I had approached other men, a look while passing on the street, followed by another look and then an introductory remark. My tricks this way, however, were simply enjoyed and devoured, disappearing as fast as Chinese takeout.

When he turned thirty Dennis announced he was stopping dancing. “I can’t dance forever,” he said somberly to me one day on the phone, by which I knew he meant his dancing had become painful. He had started seeing a therapist, having been sidelined with pulled tendons and muscles. “And I did what I wanted to do,” he added, and then asked me if I wanted to start acting classes again. We took a class together at a studio in the West Village, even though I had had some moderate success performing in a repertory company and a string of television commercials. A few weeks later, when Dennis started to worry that his body would become lumpish and paunchy if he abandoned all exercise, I convinced him to take a membership at my gym.

At the gym Dennis was something of a minor celebrity; several men had seen him dance, others simply admired his body. I was always awed by the sight of his body unclothed: tight and lean, his skin soft and luminescent as an unraveled bolt of silk. He seemed so youthful and innocent in the locker room of bodybuilders, and though he was constantly approached by men offering advice on how to broaden his shoulders, thicken his legs, and bulk up his chest, I think these men would have been happy just to take him home the way he was. Dennis easily became addicted to going to the gym; there he could stretch and work his muscles with confidence, without the fear they would be torn or damaged by performance. Sometimes he would go twice a day, first with Joel in the morning, then again in the evening with me. Once, when we stood side by side in front of the locker-room mirror in nothing but jockstraps, I noticed that his pencil shaped dancer’s physique had been remodeled to the proportions of his athletic ancestors. I asked him how he thought I looked, and I knew, as he regarded my image in the mirror, he was trying to be both impartial and comic. “You have great triceps,” he said. “Too bad mine don’t look like that.”

Now, standing in front of a mirror mounted to a column that rises to the ceiling of this floor of the department store, I watch Dennis, in a down-filled jacket, twist his waist first left, then right, studying the angles of the coat the way he once studied our bodies. He slips his hands into the pockets, hunches his shoulders, and pouts like a model, and then he bends his head down but lifts his eyes up, running his fingers through the strands of his thinning hair. Suddenly his face becomes pale and I notice his jaw clenching. He quickly removes the coat and hands it to me. “Bathroom,” he says like a child with a limited vocabulary. I hastily rehang the coat and follow him up the escalator.

* * *

Years ago I had a friend who used to cruise the fifth-floor men’s restroom of this store. Today it is empty except for Dennis and me. Dennis has thrown up twice and now stands in front of a sink, splashing water on his hands and face. When he finishes I hand him some paper towels and help him dry his neck.

“Okay?” he asks, as much a statement as a question, as though he had been waiting on me to leave. He grips my elbow with his left hand and leads me to the door, though I am not the one who needs to be supported.

Four months ago Dennis was hospitalized for pneumonia, brought on, he thinks, by the sudden chill of turning on an air conditioner to dispel the summer heat. He has known for ten months he has carried a virus within his body that is slowly, deliberately, destroying his immune system. For a while he neglected his diagnosis, or at least avoided thinking about it. Joel was also sick, having been diagnosed a year and a half before. Joel’s first symptoms were swollen lymph glands, low fevers in the afternoons, heavy sweating at night, and constant exhaustion, attributed, he said, to his mounting work load. After Joel was hospitalized with pneumonia, he started Bactrim, had a bad reaction, and then switched to pentamidine, which caused him to develop scaly rashes and diabetes. Dennis stopped going to the gym, acting classes, or auditions and turned down a role in a daytime soap opera to stay home and take care of Joel. Joel, however, kept working as much as possible—half days at the office, a few hours at home—but his anxiety over working, his anger over his illness, his terror of dying, and his fear of losing Dennis only made him grow worse.

Joel was not the first person I knew to become sick from this virus, nor the first I knew who had died. Though I had watched a friend lying helpless in a hospital bed slip from semiconsciousness into a coma, and Dennis knew a dancer who had leapt from the ninth-floor terrace of his apartment, our first acknowledgment to each other of our fear of this disease was at a Village café one night in a brief, apologetic conversation, questioning each other on the practice of safe sex. Yet, as other friends became sick, the shock of their deaths, the huge number of those infected, and the predictions for the future left us absurdly inarticulate with each other. The afternoon I met Dennis at a cinema on the East Side and noticed his posture was less than perfect, his steps were sluggish and his speech was slurred, I knew, before even asking, that something was now happening either to himself or to Joel.

Once Dennis told me Joel’s illness was the most difficult and the most intimate period of their relationship. He felt strong being able to take care of Joel, helping negotiate the labyrinth of doctors, medications, and problems. He arranged a support system of friends for shopping, cleaning, cooking, and taking Joel to the doctor. He kept abreast of the latest treatments and therapies, medical and homeopathic, and together they experimented with meditation and visualization. At night, before going to sleep, Dennis would make Joel list the things that were bothering or depressing him, so Dennis would know—could try—to make Joel’s time more comfortable. Dennis was able, as if by instinct, to know when Joel was holding something back. Often he could finish Joel’s thought before it was spoken. Over a period of almost two years, Joel battled pneumonia five times. A month after Joel’s funeral, Dennis was in the hospital.

Now, thirty-eight pounds thinner, his hairline receding, his olive skin ashen, his eyes hollowed, darkened, by medication and grief, Dennis has entrusted his security to me and a new winter coat. He tries on a denim jacket, and though I think it looks good on him, he is able to read my thought that it will not offer much warmth.

“I just wanted to see what it looked like on,” he says, his eyes widening as he looks at himself in the mirror.

Together we sort through the racks and he tries on a wool knee-length topcoat, gray and businesslike, and then a bright-red cotton ski jacket which has zippers on the sleeves. Even though Dennis knows I detest department stores—even the thought of shopping—over the years of our friendship I have helped him pick out a microwave oven, a video-cassette player, several swimsuits, and Christmas presents for Joel. Dennis likes to look at all the alternatives before making a purchase. Normally I have little tolerance for such methods; I usually know what I want before I ever enter a store. Once, several years ago, Dennis and I had our one and only fight over some shirts I had rushed him into purchasing. When he got home and found they were long-sleeve instead of short, he called and demanded I pick them up immediately from his apartment and return them to the store.

Today I do not rush him. In fact, I point out other styles, other colors for him to try. Watching him change coats, I am again reminded of how our relationship has changed. In the last three months I have sublet my apartment in the East Village and moved in with Dennis, and together we have started him on a macrobiotic diet he had heard was successful. My last acting job, five weeks ago, was a day’s work in a music video; I have told my agent the only work I can now accept must be short-term, and with the understanding I might have to cancel. When I’m not running errands, the remainder of my time is spent with Dennis. My greatest fear for now is that he will lose his will, his desire, to live.

Dennis slips on a goose-down-filled parka, dark-green cotton, with a detachable hood which dangles across the width of his back. An elderly woman, nearby with her husband, catches Dennis’ reflection, smiles, and nods.

“It does look good,” I say.

“Sold,” he says, laughing, and turns to me. “Now it’s your turn.” He weaves through the aisle, stopping in front of a display of leather jackets so expensive they are chained to the rack. I shake my head but, before I can say “No,” Dennis has lifted one up for my approval.

“Don’t worry,” he says, inspecting the price tag. “I know you can afford it.”

* * *

When Joel died he left Dennis everything he had: his books, records, furniture, clothing, the West Side co-op, stocks, and a sizable life-insurance benefit. Joel’s family had been well off; plans for his parents’ retirement, medical benefits, and financial needs had been made many years ago. As Joel explained to Dennis before he died, his parents didn’t need the money, and his sister and her two children were provided for by her husband. “Besides, I want Dennis to have everything,” Joel said to me one night at the hospital. “After all,” he added with a wry smile, “it’s the least he should get for putting up with me for eight years.”

As the beneficiary of Joel’s will, and through Joel’s system of setting up joint accounts and living trusts, Dennis has more money than he desires to spend. Though Joel did not know about Dennis’ own illness until a month before he died, he suspected that Dennis, too, would become ill. He arranged complete medical insurance and a disability plan for Dennis, both of which now pay his bills and provide additional income. This morning Dennis asked me to hire a car and a driver to escort us around town; his request, I know, was intended to give our outing more ease, not propelled by whimsy or extravagance.

“I’ve been lucky,” Dennis said as we rode downtown to go shopping. And I know he didn’t mean his new, sudden wealth. He was feeling good; we had just left the doctor, who had told Dennis his T-cell count had stabilized and had written him a prescription to relieve the nausea. “I’ve loved and been loved,” Dennis added with a wistful laugh, and stretched his legs out fully before him. “What more could I want except a little more health? There are people who have it worse off than me.”

“Someone’s going to be very rich when all this is over,” he continued. “There’s a pot of gold at the end of the storm.” I offered no comment and turned my head away from him to look out at the street: signs, stores, and strollers whirling past my vision. He knew this was a subject I refused to discuss with him. Dennis has begun putting his money into joint accounts and living trusts, as Joel did before him, only this time the other name is mine. I told him I didn’t want it, didn’t need it; it should be given to charities or organizations that can use the funds and the help. Money can’t buy for him, for me, what I want. It cannot buy time: past, present, or future. I can’t purchase Dennis’ health, Joel’s life back, or something to erase my own fear of dying. “You don’t have to use it if you don’t want to,” Dennis said when he told me of his plan. “But it’s there if you want it.” Security, as it were, like a winter coat.

Despite my objections, Dennis has purchased a leather jacket for me. Though he has enough money with him to pay in cash, he paid for both coats on his credit card. His reasoning is one Joel taught him shortly before he died: no one is responsible for a dead man’s debts. Now the coats have been folded and placed into two large shopping bags, which I swerve either in front or in back of me to avoid hitting people as we travel across the main floor. Suddenly the store has become busy. Dennis walks ahead of me, sidestepping around the shoppers streaming in through the revolving door.

The car is waiting for us at the corner. Outside, I am momentarily confused by the bright October light, and, jostled by the crowd, I lose sight of Dennis. It is a crisp, clear autumn day, the air so light, so buoyant, not even the swarm of shoppers can agitate me. When I spot Dennis he is standing on the curb near the car. As I approach him he observes, just as I do, a street sign that reads “Broadway.” And then there is a moment so private, so personal, it is priceless. Dennis smiles, making sure I notice, straightens his posture, and springs quickly from flexed knees to the balls of his feet. Effortlessly, gracefully, he spins through a double pirouette. I could never do even one without losing my balance. And then he is gone, dancing out of sight behind the opened door of the car.

________

“Winter Coats” first appeared in the author’s collection Dancing on the Moon: Short Stories About AIDS, published in hardcover by Viking in 1993 and in paperback by Penguin in 1994 and reprinted by Chelsea Station Editions in 2011, and Still Dancing: New and Selected Stories, published in paperback by Lethe Press in 2008 and reprinted by Chelsea Station Editions in 2011.