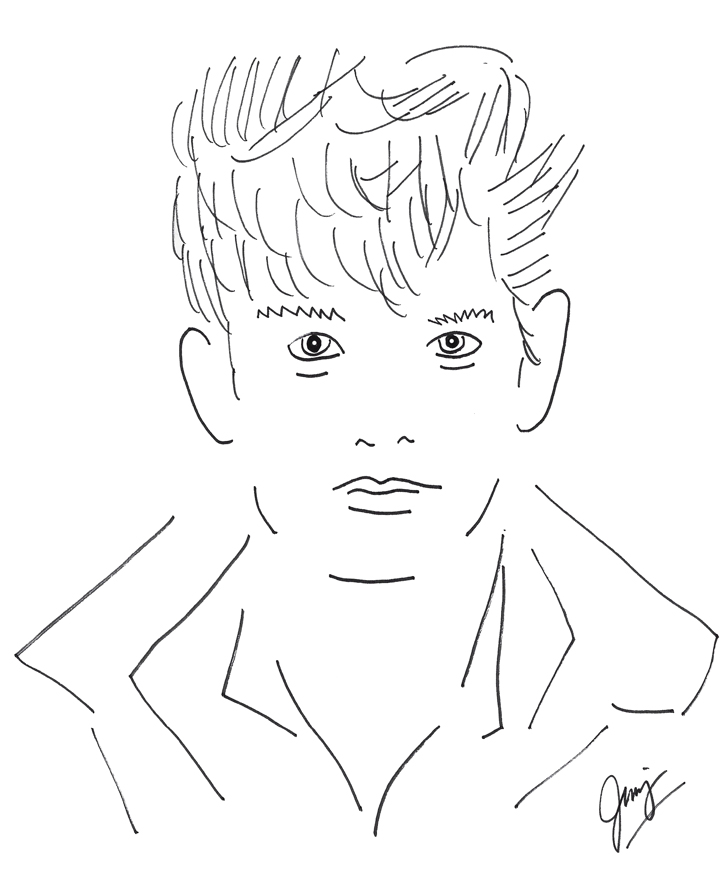

sketch of Robert Mapplethorpe

by Jameson Currier

ink on paper

20250107004

On Mapplethorpe

Review by Jameson Currier

In the purest, most simplistic way, Robert Mapplethorpe could be remembered as the greatest studio photographer of his generation. On one level, his black and white photographs can be viewed for their emblematic standard of beauty, whether that beauty was to be found in an orchid, a bald head, a navel, or a scene of sadomasochism. But to remember Mapplethorpe on only one level is, of course, to dismiss the complexity and controversy of both the artist’s work and life. As Patricia Morrisroe’s fascinating and sexually candid biography of the artist reveals, nothing about Mapplethorpe was merely black and white.

Instead, what is apparent in Mapplethorpe is exactly what made the artist’s portraits so vibrantly alive with color — the passions and obsessions of a gay man exploring and defining his sexuality. In fact, the erotic and exotic details of Mapplethorpe’s personal life have now become as much a part of the Mapplethorpe mystique as the artist’s work itself has: his themes and life overlapping, particularly his preoccupation with images of death and violence, his worshipping the black male physique, his fascination with the devil, and his desire to transform the ugly or freakish into works of beauty. Throughout his life, Mapplethorpe photographed men whom he physically desired and had affairs with and his photographs now serve as a diary, of sorts, of his sexual adventures and appetite.

But Mapplethorpe’s life, like his art, was marked by dichotomy. As Mapplethorpe was becoming famous in Manhattan art circles for the scandalous and liberating frankness of his gay S&M portraits, for instance, he was also petrified that his parents in nearby Floral Park would discover he was gay.

“My life is more interesting than my art,” Mapplethorpe told Morrisroe in one of the sixteen interviews she conducted with the artist before his death in 1989 at the age of 42 from AIDS.

Morrisroe also interviewed more than 300 friends and acquaintances of the artist who knew Mapplethorpe in his various permutations and incarnations, from Catholic schoolboy in Queens to college ROTC cadet, from hippie to celebrated artist. Though Mapplethorpe was obsessed by male beauty, ironically, his most enduring relationship was with the female poet/rock performer Patti Smith, and Morrisroe’s accounts of this long-standing friendship form one of the most absorbing cores of this book.

Morrisroe, however, does not shy from presenting a full examination of Mapplethorpe’s gay relationships either, particularly the part sexual, part paternal one he shared with art patron and collector Sam Wagstaff. Nor does the author treat her subject with reverential seriousness, noting, for example, Mapplethorpe’s ongoing greed, social pretension, racist views, and that the artist used drugs daily, never taking a picture “without first getting stoned.”

Though Mapplethorpe had achieved a considerable success and reputation while he was alive, the greatest surge of interest in his work came when news of his AIDS diagnosis moved through art society. Yet it was only after his death that he became famous as an artist when the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. abruptly canceled a retrospective of his work in 1989. Partly funded by the National Endowment for the Arts, Mapplethorpe’s “The Perfect Moment” exhibit ignited a fierce debate over federal financing of sexually explicit art. A year later, when the exhibit arrived at the Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati, the director of the museum was charged with pandering obscenity and misuse of a minor in pornography.

Today, remembering Mapplethorpe, it is impossible not to factor in the importance of the Cincinnati trial and its resulting publicity into the awareness of the artist’s work, for the Cincinnati trial became a test case for current standards of obscenity, and Morrisroe includes a chronological account of this in an epilogue to the biography.

Whether Mapplethorpe was an important artist is now clouded by the larger issue of the relationships of photography, art and pornography. “The whole subject of exploring sexuality is a very important one in photography,” Philippe Garner of Sotheby’s auction house states in Mapplethorpe, and Robert will certainly be regarded as a pivotal figure.” Remembering Mapplethorpe now means remembering the photographer as a symbol of artistic freedom, even though his death from AIDS may been viewed by some as the haunting conclusion to an era of more liberated and unhindered sexual expression.

Mapplethorpe: A Biography

by Patricia Morrisroe

(Random House, 1995)

__________

Robert Mapplethorpe died March 9, 1989 at the age of 42.

This review was published as “Remembering Mapplethorpe,” in Body Positive, June 1995. It was also published as “A Too-Candid Camera,” The Dallas Morning News, July 2, 1995.