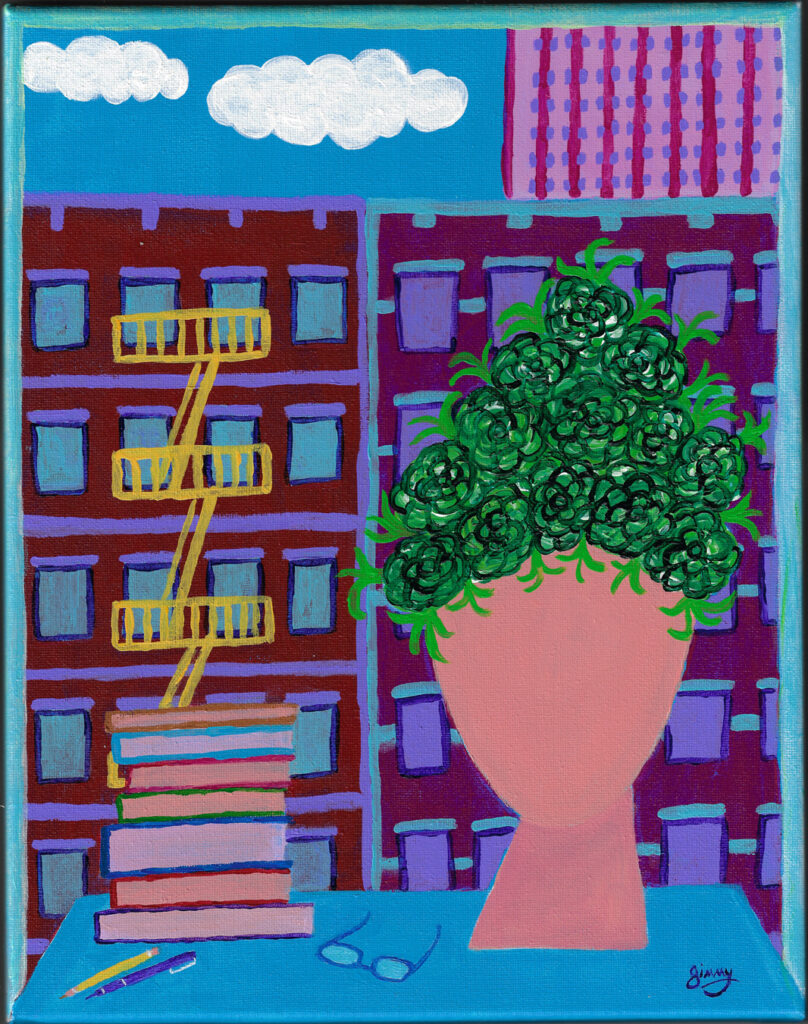

West Side Scene

art by Jameson Currier

acrylic on canvas

20220808001

This article was originally published in Chelsea Station, Issue 3 (2012).

That Gay Place

by Jameson Currier

The books I read when I was in my early twenties during the late 1970s and early 1980s made a significant impression on my gay consciousness: the importance of coming out; the concept of pride; and the political, social, and religious hurdles associated with those essentials. But these books also instilled in me a desire to visit the places where their stories took place. At the recent Lambda Literary Foundation awards in Manhattan, writer after writer praised Armistead Maupin and the impact Tales of the City had on their lives and careers (and deservedly so). I was filled with joy the first time I read that book and it was instrumental in my wanting to become a writer of gay stories. I was twenty-four when I discovered the novel in 1980 and I wanted to see San Francisco myself as a young gay man, just as Maupin’s character Michael “Mouse” does. My visit would not happen until a few years later when my job as the advance publicist for the national tour of a Broadway show landed me for a week’s stay in a Union Square hotel. With me I had the torn-out pages of the San Francisco sections of Gayellow Pages and the Spartacus travel guide, essential tools to navigate gay life in other cities in the early 1980s, as well as my memories of several of Maupin’s Tales books.

It was a heady and somber experience. By then, AIDS was changing the landscape of gay life in San Francisco and elsewhere. And I was well aware of the importance of gay history, recorded, unrecorded, and ever-evolving. When I first landed in Manhattan in 1978 as a young man struggling to accept his homosexuality I knew few facts of gay history. The new friends I met in graduate school and my first jobs in the theater served as my gay educators: Did I know that Marlon Brando and Wally Cox were once roommates? That Blanche’s husband was gay? Why Brick was troubled? Or the rumor where Edward Albee had seen the line of graffiti scrawled: “Whose Afraid of Virginia Wolf?” And then gradually: Had I read Oscar Wilde or Walt Whitman? Did I know about Leonardo and Michelangelo? What did I think about Truman Capote? Or Gore Vidal? Or Andy Warhol?

It was time of an astonishing awakening for me. Books such as Vito Russo’s The Celluloid Closet: Homosexuality in the Movies and Gay Source: A Catalog for Men by Dennis Sanders were beginning to be published and available in New York City bookstores, and even though I was accepting of my sexuality I felt I had a lot to learn about becoming part of the gay community. I was working as an apprentice publicist on Broadway and off-Broadway productions by Harvey Fierstein, Tennessee Williams, Truman Capote, and Peter Allen, and was hearing gossipy backstage stories about gay actors and playwrights from the lesbian couple I worked for as well as my new friends in the theater. I recall I had a particular fascination at the time with the history of Greenwich Village. I would take long walks, street after street, locating the places where James Baldwin had lived or where Edward Albee’s play had premiered, where Truman Capote had gotten drunk, or where the Stonewall Inn had been located. All this was wrapped up in visiting the current gay spaces of the era with friends and co-workers such as the Ninth Circle, Julius’, Paradise Garage, 12 West, Ty’s, Uncle Charlies, the Oscar Wilde bookstore on Christopher Street, and Charles Ludlam’s theater in Sheridan Square.

Edmund White’s States of Desire: Travels in Gay America also made a formidable impression on me during this time. It simultaneously cemented the diversity and similarities of gay life around the country. White had traveled to Dallas, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle, Denver, Boston, Washington, D.C., and other cities and he had spoken with numerous friends and gay community leaders and activists about their personal and social lives, careers, and their place in their community and neighborhoods. While this wasn’t a travelogue per se, really more of a social record of the time, White did recount his opinions and adventures as any memoirist would. As a writer, I have reread this book many times to study the author’s voice, structure, and questions he posed of his subjects and himself. I also consider this work as the touchstone for two distinct branches of gay nonfiction that I have since come to treasure reading, both related to “the gay place”: historical accounts of gay life and events related to a specific location, and gay travel memoirs.

Of the former, there are many fine and memorable works that have kept me enthralled for hours since White’s book was first published in 1980, but seminal to the genre are those by academics who reveal unreported or forgotten facts and events. My favorites include George Chauncey’s Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940; Charles Kaiser’s The Gay Metropolis; Lillian Faderman and Stuart Timmons’ Gay L.A.; John Howard’s Men Like That: A Southern Queer History; and James Sears’ Growing Up Gay in the South: Race, Gender, and the Journeys of the Spirit. These are all deep and respectful historical examinations, but two digest books that I continually enjoy revisiting for delightful glimpses of gay history, rumors, and gossip are those created by Leigh W. Rutledge in the late 1980s: The Gay Book of Lists and The Gay Fireside Companion. In recent years I have discovered and enjoyed the illustrated local history books published by Acadia Press, among them Gay and Lesbian Atlanta by Wesley Chenault and Stacy Braukman; Gay and Lesbian Philadelphia by Thom Nickels; and Gay and Lesbian San Francisco by Dr. William Lipsky and Tom Ammiano. Equally delightful is Greetings from the Gayborhood by Donald F. Reuter, who chronicled the evolution of gay neighborhoods in twelve cities.

Of the latter category, I recall seeing a book review in The New York Times in 1987 for The Songlines, a nonfiction narrative by Bruce Chatwin, about the author’s travels to Australia to learn the meaning of the Aborginals’ ancient “Dreaming-tracks.” Accompanying the review was a headshot of the writer, an incredibly handsome blond-haired British man. I recall stating this fact to my friend Kevin, whose immediate response was, “You know he’s gay.” I didn’t know that, but Kevin did, yet another unknown gay fact that was passed along to me by a friend. But suddenly a whole new genre of reading opened up for me: the gay travel memoir, a narrative form much like Maupin’s novels, of a man on the outside looking in at wonder of a different world or community and saying, “Did you know this? Did you know that? Look at what I have just discovered.”

Gay travel memoirs now seem to fall into two categories: accounts of the short-time visitor—best exemplified by Wonderlands, a collection of nineteen essays edited by Raphael Kadushin, whose highlights include Philip Gambone’s visits to Asia, Boyer Rickels examination of Italian men, and Tim Miller’s life as a travelling performance artist, and Travels in the Muslim World, a collection of eighteen essays which include editor Michael Luongo’s adventures in Afghanistan—and accounts of the longer visits and examinations of a culture or community, whose notable examples include John Berendt’s look at Savannah and a specific crime case in Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil and Tobias Schneebauum’s Keep the River On Your Right, about the author living with a tribe of cannibals in the jungles of Peru (and which became the basis of a terrific documentary). Other notable books in these genres include Michael Cunningham’s Land’s End, an idiosyncratic look at Provincetown, Massachusetts; The Flaneur by Edmund White, about the city of lights; Florence: A Delicate Case by David Leavitt; and Volleyball with the Cuna Indians by Hanns Ebensten, a series of travel vignettes by a pioneer in the field of organized gay group tours. And several new books have appeared on the horizon which are now condensing gay history, pride, memoir, and the love of place all into one book. These include the Lambda-winning Love, Bourbon Street: Reflections of New Orleans, edited by Greg Herren and Paul J. Willis, a remarkable series of love letters about the Big Easy published in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina; Love, Castro Street: Reflections of San Francisco, edited by Katherine V. Forrest and Jim Van Buskirk; and the most recently Love, Christopher Street, edited by Thomas Keith, featuring twenty-six contributors, including Thomas Glave, Felice Picano, Christopher Bram, and bookended by comics Bob Smith and Eddie Sarfaty.

___________

“That Gay Place” was originally published in Chelsea Station Magazine, Issue 3 (August, 2012).