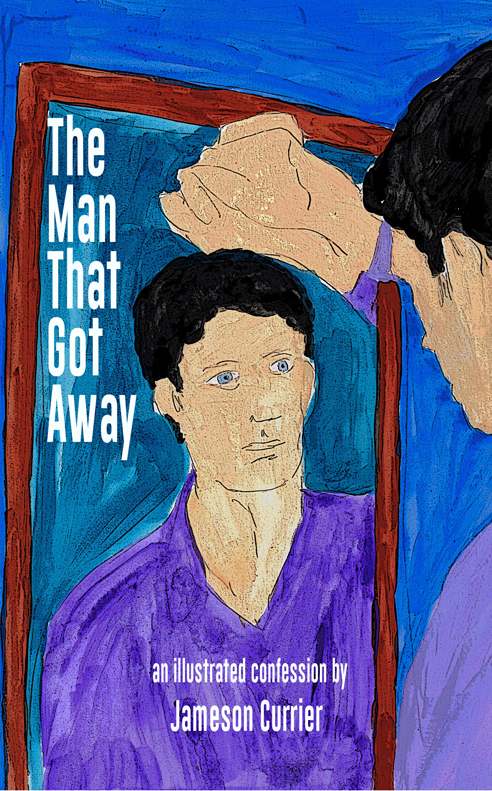

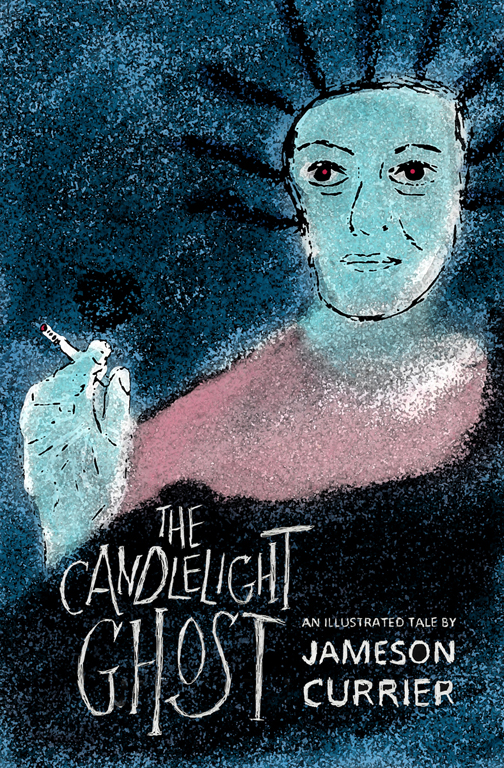

from Based on a True Story

illustration by Jameson Currier

by Jameson Currier

“Are we expecting the Royal Family?” Aiden asked.

While Harley started the fire in the hearth of the Great Room, Aiden and Scott had followed me into the kitchen, Zero close behind them, delighted by the change in rooms and hoping it meant food for him. Scott had the good sense of staying out of the way, stooping down to his haunches and petting Inky, but Zero stayed eagerly at my side, convinced that I would feed him something if he just looked up at me with his sad eyes and begged. Aiden, too, had decided to hover close beside me, reading my recipes which were hand-written on the back side of a stack of green-colored index cards which listed, in order of succession, the Kings and Queens of England.

“I’ve used these since college,” I answered him. “Junior Year. History of the British Empire. I can do the Plantagenets, Yorks, Tudors, and Stuarts, but the Hanovers still throw me.”

“You might have a great marketing scheme here,” Aiden said. “Learn world history while you cook.”

The first Thanksgiving dinner I cooked for friends was the year Jeff and I shared an apartment off-campus. I was not a good cook, knew nothing about cooking, really, and had already developed a reputation among my friends as a bad one from the time I had cooked frozen broccoli with a half-cup of salt for a dinner party of six. (The recipe on the back of the box had instructed to boil the broccoli shoots in a half-cup of salted water, which I had taken, literally, to mean a half-cup of salt.)

There were to be five of us that year for Thanksgiving dinner, 1975—myself, Jeff, Neal, and two girls from the University choral group who had not traveled home during the break in classes—Lee-Anne, a statuesque sorority girl, and Tracey, a short, overweight brunette who had a crush on Neal. I had called my mother to tell her I would not be coming to the house for the holiday and would be eating with my friends and in the same breath asked her for her recipes, which I wrote down on the back side of index cards I had been using to outline the royal succession to the throne of England. This was long before the Internet, of course, and I had spent close to an hour with my mother on the telephone, writing down how to wash and baste a turkey, how to prepare the stuffing, how to make a string bean casserole and a cranberry Jell-O salad, when to start making the gravy, when to heat the pie—all the things I had never paid attention to when she had done it for our family. That meal had turned out fine once Neal had decided that our oven did not cook at the temperature it read on the dial, though there had been a bit of a squabble over dessert as I recall, or, rather, a bit of a broken heart when Neal told Tracey that she had put too much sugar in the frosting of a cake she had made for the occasion and she had reacted by breaking into tears.

“No cookbook?” Aiden asked. He looked alarmed. Or mock-alarmed, as if I were the queerest gay man ever to step foot in a kitchen without a professionally-written bible of what to do. I was not about to admit to him that I was a lousy cook—that Harley generally did all of the cooking for us on the outdoor grill when the weather was fine and that my idea of a well-balanced meal was to eat out at a restaurant. Instead, I answered rather proudly, “Every year I add a little something different.”

I picked up one of the cards from the stack, flipped it over, and said, “This was ‘98, I made an apple cobbler that year for a guy I was dating—Russell—who turned out to be a bit of a rotten apple, himself—but the pie was great. And this was ‘87—the year Kyle ordered an organic turkey. Scott was there for that one. The pan had a hole in it and we had a terrible smoke problem in the apartment.”

Scott looked up from the floor and Inky and said, “Kyle was in such bad shape it didn’t bother him. The rest of us were coughing and our eyes were tearing.”

“And this year?” Aiden asked.

“A pumpkin pie.”

“A real pumpkin pie?” Aiden asked, again with his mock-alarm expression and tone of voice.

“Of course not,” Harley answered as he walked into the kitchen and rinsed his hands at the sink. Zero quickly abandoned me knowing for certain he could expect a treat from Harley. “It’s from a can.”

Aiden turned to me and asked, with a disappointing tilt of his head, “And the crust?”

“Store bought,” Harley answered again for me. “But he bakes it up all just fine.” He reached into a box of dog treats and held one up in front of Zero’s eyes. The dog leapt up and snatched it from Harley’s fingers, did a little circle on the linoleum, his paws clacking-clacking-clacking till he settled into a corner and began gnawing at his bone.

I was eager to get the topic of discussion away from my cooking skills, worried that sooner or later Scott might dredge up a memory of burned waffles from the summer house in the Hamptons, and I asked Aiden if he was ready for a cocktail yet.

“On an empty stomach?” he answered. “I shouldn’t!”

“You should,” Scott said. “It’ll calm you down. And I’ll join you.”

While the three of them hustled about the kitchen—Harley pulling down glasses and ice cubes and showing them our supply of liquor and mixers, I threw away the cans of cream of mushroom soup that I had used to make the green bean casserole and tried not to feel like too much of a cooking fraud. I’d never admit that I was a sentimental man, because I wear my sentiment like a protective apron, and these note cards represented close to thirty years of my holiday memories that I had religiously refused to let go of—the stain on the recipe for gravy was from the year I’d cooked for my cousin and her boyfriend the first year I landed in Manhattan; the burned edges on the card for the recipe for stuffing was from the year I cooked the organic turkey for Kyle and, while rescuing the burning turkey pan, the card slipped too close to the gas flame.

Kyle had always gathered his friends for a home-cooked meal at his apartment during the holidays and it was my intention to keep up the tradition the year he was too ill to do it himself. I had met Kyle at a holiday party on the Upper West Side, one of those friendly but over-crowded gatherings that take place in apartments on West 77th Street on the Upper West Side on Thanksgiving eve, when the giant cartoon-character balloons are blown up along the block for the next day’s parade. Snoopy, Kermit, Popeye, and Mighty Mouse were lumpy rolls of rubber when I followed Scott into a doorman building and took the elevator to the 17th floor. Kyle, who was a friend of the actor who had lucked into subletting the apartment, was standing near the windows looking down at the saggy bloat of Popeye’s forearm and calculating the net worth of the view when Scott introduced us to each other.

Kyle had long, limp, reddish-brown hair, a high forehead, and small dark brown eyes brightened by the glint of the bookish, silver wire-rimmed eyeglasses he wore. His face was too strong and serious to allow his impish sexuality to become annoying, but because he was always meticulously groomed—hair evenly cut around his small ears, his jaw closely shaved and with a whiff of aftershave at his collar—it was difficult not to fantasize undressing him.

I had gone home with Kyle that night to his apartment in Hell’s Kitchen and had stayed until the next morning, when he awoke cranky and hung-over and hurriedly tried to get rid of me before he began cooking his holiday meal for “eight or nine of his dearest and closest friends,” one of whom was Scott and to whom I protested to later that night on the phone when he had returned to his apartment stuffed and tired from Kyle’s elaborate holiday feast. “He didn’t even have the decency to ask me if I had any plans of my own,” I said, though I was not dismayed that I had been overlooked and ignored—at that moment I was simply a one-night trick for Kyle and I had certainly treated some of my other sexual partners worse than Kyle had treated me. And the truth was I did have plans of my own in place, though I was also somewhat miffed that Scott had chosen to dine with Kyle and his fabulous crowd of in-the-know urbanites instead of with me and my cousin from Westchester and her new boyfriend, though I couldn’t blame him for his choice. (Ours was an awkward dinner, made even more uncomfortable by my cousin’s boyfriend’s visible disdain of an openly gay man.)

Kyle and I dated each other a few more times that holiday season, but I found him too passive in bed and too pretentious out of it to want to be boyfriends with him. And, since we had so many good friends in common (not to mention several of the same ex-boyfriends), we soon became closer friends than significant others, brothers, really, instead of lovers, more able to tolerate each other’s faults. Scott and Kyle had also cultivated a gently antagonist relationship which I enjoyed being an audience for, since it was often carried out as if they were characters in a play. Scott was traditional, structural, and habitual; he grew up with old Southern money, debutantes in white gloves, and mint juleps on the plantation porch, that sort of thing, and his opinion was often based on etiquette and education, both social and literary. Kyle, however, was faddish and trendy—always on the run to visit whatever gallery or restaurant had been anointed as au courant and en vogue. They often passionately disagreed on the arts, particularly on new wave films or avant-garde plays that Scott had negatively reviewed—“I’m sorry, Kyle, but where was the plot?” Scott would argue, or “It was a lovely melody, yes, but the dialogue was out of a soap opera.” Kyle, in turn, would huffily respond, “Don’t be so small, Scott, learn to think outside of the box!” or “You’re condemning it simply because it’s different, not because you don’t want to admit it was good.”

And, as fate would have it, Kyle and Scott became my surrogate family in the city, and for several years later, when I had been invited to attend Kyle’s holiday soirees (where I had also helped him cook), I would often kid him that he had thrown me out in favor of his more wealthy and snobbish friends, all of whom seemed to change or just simply disappear from year to year. Kyle had many famous friends, in fact, including several Broadway actors (one of whom was a Tony winner), a Soho gallery owner, and several writers at work on various new projects—all of whom I would never see or hear about during the year until these annual holiday gatherings. Kyle also liked to be pretentious with his menu, using olive oil imported from Greece, for instance, because it had a more fruity taste, or buying imported black Himalayan truffles because they were less pungent than the European brands, but by then I had grown to consider his pretentiousness more ironic than serious, a faux-pretentious, as it were, particularly when he would describe the hors d’ouevres of shrimp wrapped in seaweed as Asian fusion or explain that the chunky tomato pasta sauce was prepared the way it was in a particular hill town in Campania.

But Kyle was a much better host than I ever learned how to be; he didn’t fret or hover as I did; he laughed and nodded, placed his hand on shoulders, interrupted conversations to refresh drinks. And he was much more hip and cutting edge than I ever cared to be, always quick to ask his guests, “What’s been going on with you?” or “Kindly give me all of the details, please, you know how interested I am in all of this.” I attributed his sense of ease with having been a life-long New Yorker and a product of a broken home, living in a succession of Manhattan apartments with either his mother or father and learning to impress their parade of suitors with his charm and quick wit.

All of his famous and long-standing family friends evaporated when he became ill, of course, or, rather, as he progressively deteriorated from AIDS, a secret which he kept hidden from his parents as long as he could (but which did not escape their prying eyes). Scott and I were left monitoring his doctors and medicines and disclosing the truth to anyone we could find to tell it to, both close and casual, professional or medical, especially when Kyle took a leave of absence from his job as a publicist after an extensive hospitalization for a variety of items which no doctor could seem to pinpoint the exact cause of, except from an ever-weakening immune system.

After his death, I had tried to keep up Kyle’s Thanksgiving tradition going for as long as I could, but his glittery crowd was not interested in re-assembling for such a sure-to-be morbid gathering of my bad cooking, and as more of my own friends were lost or moved away or became involved with other partners, my Thanksgiving routine became more intimate again, usually entertaining my boyfriend-of-the-moment by candlelight and a simple meal, if he were in town and willing to be subjected to my cooking. Now, after so many years of Thanksgiving without him, my memories of Kyle seemed reduced to smells and stains on recipe cards.

“You know how to cook a pecan pie?” Scott asked. It was his turn to hover about me, drink in hand, looking at the note cards.

“I tried it one year,” I said. “Not much success.”

“What kind of Southern boy are you?” Aiden asked. They had changed places; now, Aiden was now on his knees petting Inky and looking up at me from the floor. “Don’t you know you’re supposed to doctor it up? More rum the better.”

“Or bourbon,” Scott added, close behind. “That’s how my mom always did it.”

“Touché,” Aiden said, and raised his glass in the air, his face breaking into a bright smile.

“Who’s Mitch?” Scott asked, still thumbing through my note cards. “Did I ever know a Mitch?”

“What do you mean?” I answered him, feeling the blood drain from my face. I did my best to hide my astonishment as I took the notecard from him and looked at where I had scribbled in pencil, years before, “Call Mitch.”

“He was a guy I met when I first moved to the city,” I answered apprehensively, shifting my eyes away from the card to hide my surprise of finding his name there. “I was supposed to get together with him Thanksgiving night. I guess I never erased it.”

That, of course, was the short version of my friendship with Mitch, but there was a longer and more problematic shape to it that I had never admitted to anyone. Mitch had big blue eyes, wavy black hair combed back to emphasize his widow’s peak, and a compact, lean body as suggestively obscene as a porn star, full of pulpy veins snaking across the muscles of his arms and thighs. He had nothing of Scott or Kyle’s refinement, the son of a steel worker and the last child in a family of six in northern Pennsylvania. I had met him when we were both leaving the Club Baths on First Avenue one Sunday morning in 1978 and he had asked me if I had met anyone interesting (which I hadn’t) and I asked him if he wanted to join me for breakfast at a diner (which he did). There was an intense moodiness to him, though his speech was often short, staccato phrases and rarely a complete sentence. I was fascinated with his hyper-masculinity, the black, pebbly stubble of beard to the glossy dusting of black hair at the back of his knuckles. I always believed that since we had met coming out of a sex club that Mitch thought me more of a hedonist and sexual athlete than I truly was, an illusion that I dishonestly tried to carry off as best I could. He had a complete lack of sexual inhibition and, along the course of our friendship, I followed him through a maze of discos and backrooms in the city, places I would have never had the courage to go on my own because I wanted to be with him, wanted him to say, “Let’s just forget about all this nonsense and go back to my apartment and do it together.” Which, of course, never happened.

In many ways, this warped mentor-protégé experimentation was an extension of the relationship I had enjoyed with Jeff only a few years before, and Mitch hungrily summoned up my passion to please a handsome partner. I would have settled for giving him a blow job just once, but he was completely indifferent to my desire for him, or, rather, he had no inclination to spoil the “special friendship” he felt that he could share with me, which in his version of the story meant that I was an asexual witness to his self-gratification. Often, after coming home from the baths or a sex club where I had gone with him and watched him disappear the moment he slammed the locker door shut, I used to dream about him fucking me and crushing me beneath the weight of his body. I soon grew tired of my voyeuristic role in his life, however, and months would pass before he would call and I would again agree to follow him out into the night.

This went on for years, of course, in its perversely passive-aggressive way, until the Thanksgiving in 1987 that Kyle was too ill to cook, when one of Mitch’s sisters left me a message inviting me to a party at his apartment that night. I understood immediately the subtext beneath the purpose of her call; Mitch must have been too bad off himself to call me. Or too embarrassed to withstand my questioning. The last time I had seen him was almost a year and half before when we had gone to a bar on Columbus Avenue together and I had noticed a rough, reddish patch of skin just to the left side of the cleft in his chin. It wasn’t until I listened to his sister’s message on my answering machine that I grasped what he had told me was an infected gash while shaving was instead a KS lesion and his health must have deteriorated in the time I had not seen him, in much the same way Kyle’s had. I could not make it to his apartment that night, and had written down “Call Mitch” to find a moment to call him from Kyle’s apartment, but with the smoking pan and the burning notecards and Kyle’s rush of diarrhea before dessert, I had completely overlooked it. When I remembered a few days later, there was no answer when I called Mitch’s apartment and, when I happened to walk by his building on 19th Street a few months after that, I noticed that his name was no longer on the door buzzer and figured he must have moved back to Pennsylvania, or worst, become another casualty of the epidemic. I remember the terror I felt as I walked away from his doorway; with the diagnosis of each friend, I felt suspect and guilty of my own health. Everything seemed less rational in those years. And part of my horror was that I had no one who knew of my friendship with Mitch—he was simply not part of my close circle of friends, nor would he have ever felt comfortable there. He belonged to those idyllic days when I had first arrived in Manhattan and the pursuit of sex could be an adventure, even though my larger quest had always been for something and someone more consistent and substantial.

Years later, both Scott and Harley must have realized the guilt of my secret while I avoided their stares in the kitchen of the cabin; I’ve never been a man who could easily hide his emotions and I had frozen in thought looking at my years-old handwriting for some kind of clue to the man who had once wrote those words. Scott would have pressed me for more details if Harley’s instinctive protectiveness had not kicked in first. “When did the two of you last see each other?” Harley asked. He was referring to Scott, of course, not Mitch, bringing our friendship to the forefront of our conversation—and my mind.

Scott lifted his eyes away from the notecard and realized that Harley had directed the question toward him in an effort to change the subject. “Vegas, right?” Harley said, glancing at me.

“Just before the Millennium,” I answered.

“Five years ago?” Scott said, imitating Aiden’s way of displaying a mock-surprise—eyes bugged out, eyebrows lifted, lips rounded into a small, open “O.”

“Has it been that long?” I answered.

Four years before, 1999, instead of cooking and entertaining each other for the holiday, Scott and I had met up in Las Vegas for a week, at a time when we were both single and needing to get away from the complexity of our lives. We had wandered from casino to casino like stoned-out zombies, neither of us interested in the flashing-screeching-dinging slot machines, silently riding the monorails from Mandalay Bay to MGM Grand as if we were floating in a helium-filled balloon, regarding the bright, garishly decorated casino lobbies of the hotels as if they were filled with priceless items of art. We had gone to one of those early bird all-you-can-eat buffets, then saw a show—a Cirque du Soleil spectacular full of flying contortionists and inexplicable electronic sounds, then watched the dancing water fountains in front of the Bellagio Hotel and called it a night, retiring to our separate rooms and falling asleep as soon as our heads hit the pillow. It was a pleasant trip, neither of us even concerned where the nearest gay bar was located—both of us having been burned out by bad lovers that year.

While Scott continued to describe Vegas to Harley, I rinsed and shredded the lettuce at the sink and drained the excess water with a salad spinner, my own memory flowing from Vegas to Mitch to Kyle’s smoky apartment, while the others in the kitchen moved between the notecards, the dogs, and the refrigerator.

“Are you okay? Harley asked a few moments later when I had frozen into place. I had filled a ten-quart ceramic tureen in the shape of a pumpkin with the lettuce, carrots, mushrooms, and tomatoes and was not focused on what I should do next. “Do you need any help?”

I was trapped in another moment of sentiment; the pumpkin tureen had once been Kyle’s; it was something I had taken from his apartment after he had died because it was such a familiar part of his holiday gatherings when Scott and I were sorting through his possessions to toss away, give to friends, or donate to charities.

I looked at Harley, tried to find a way to describe this, then realized it was another thing I wanted to keep secret. “I’m fine,” I answered, shaking the remaining water on my hands into the sink. “I think we’re almost ready to eat.”

__________

“Thanksgivings” is an excerpt from Based on a True Story, a novel by Jameson Currier, published by Chelsea Station Editions, 2015.