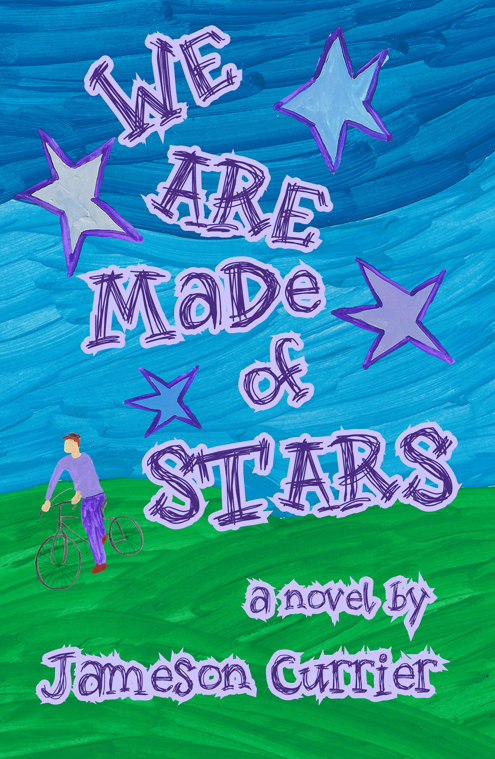

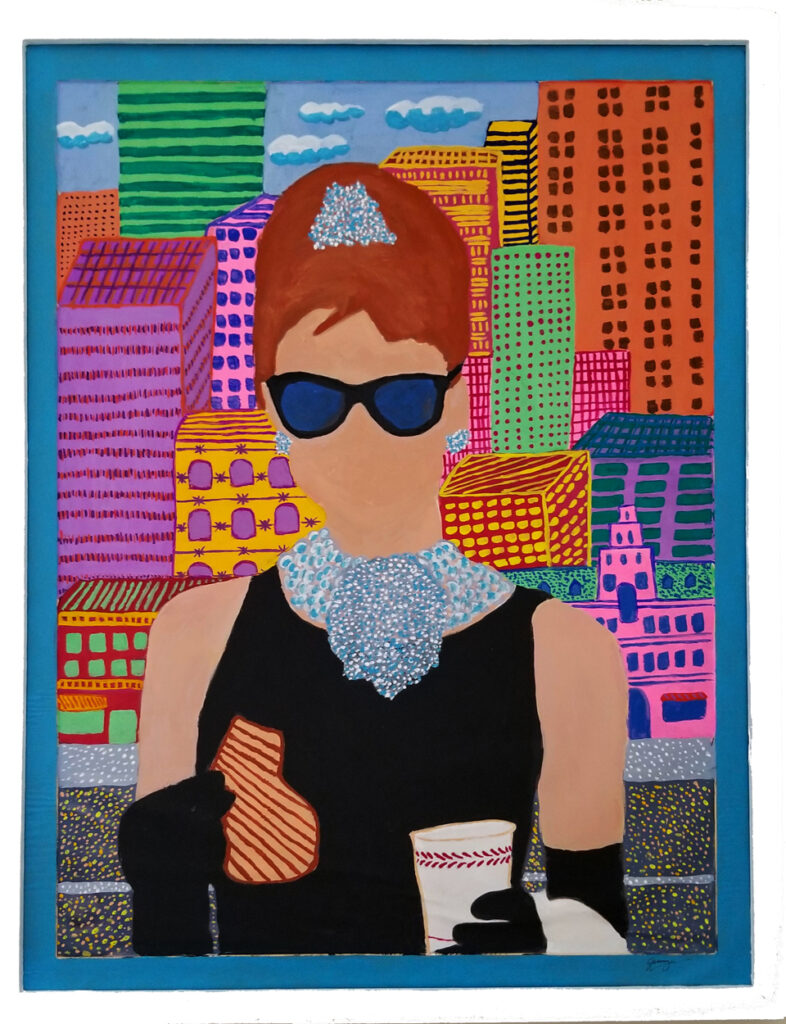

Audrey

art by Jameson Currier

Gouache on paper

20210109001

Audrey

story and art by Jameson Currier

In the late 1990s I was at the tail end of a relationship with a married man who was going through a divorce but unwilling to come out as gay except to a small group of gay friends and would-be lovers, boyfriends or tricks. He was several years older than I was and he had an income more than 10 times what I made as a temporary office worker and sometime author, journalist, and book critic. I gave up a west-side floor-through rent stabilized apartment (with a lot of maintenance issues and in a building which has subsequently burned down) to move in with him into a luxury high rise apartment on the Upper East Side of Manhattan where I was expected to contribute my half share to his deluxe life style. Our issues were not just related to the differences in our incomes and ages and the co-habitation lasted barely six months before he got the restless itch to see other guys and I moved out to another apartment on the west side. Our relationship continued for another two years or so, off and on, with a spectacular dénouement where I angrily jumped out of a moving car. It was during this off-and-on period that he gave me a birthday gift of a framed black and white poster of an Audrey Hepburn photograph of her standing in front of the windows of Tiffany’s to hang in my new apartment. In his luxury apartment, the one I had vacated, were expensive limited edition prints by Warhol, Rauschenberg, and Lichtenstein, bought from auctions at Sotheby’s we had attended together.

I admired Truman Capote as a writer and Breakfast at Tiffany’s is one of my favorite novellas, hence the reason behind the gift, and I equally adore the movie for all of its Hollywood faults, including the iconic casting of Audrey Hepburn. The framed poster hung in my kitchen alcove for a few years, gathering spatterings from the refrigerator, microwave, and stove, until one day I finally wearied of it because it had come to remind me of a time when I was not happy—or realized that I was unhappy.

I stored the poster in a small second room the size of closet (but what a Manhattan real estate agent would deem a separate bedroom) where it stayed for twentysomething years until I began to move my belongings to the farmless farmhouse upstate I had purchased shortly before I retired. I had always thought the poster was oddly and sloppily framed, and I imagine it was probably a hasty decision by my ex-boyfriend on his way home from seeing one of the other-boyfriends he maintained during our relationship. It had a one-inch beige mat border glued around the black and white poster photograph and a cheap black painted wood frame of the sorts that a college student could afford, certainly not representative of what a Wall Street trader with a high six-figure income and a growing contemporary art collection might want to display. Every time I looked at the framed poster I felt it a sad representation of a wonderful movie, in part, because it didn’t capture the colors of the movie, especially the mean reds and the sad blues which are so indicative of the character of Holly Golighltly. I always thought that one day I might disassemble the frame and figure out how to add some color to the poster—or at least get rid of the hideous beige mat. But those were the days when I worked to live and eat and pay rent and I wrote to tell the stories that needed to be told and to release them from my memory so that I wouldn’t succumb to grief and unhappiness. Repainting a bad poster gift from an ex was not high on my list of things to accomplish.

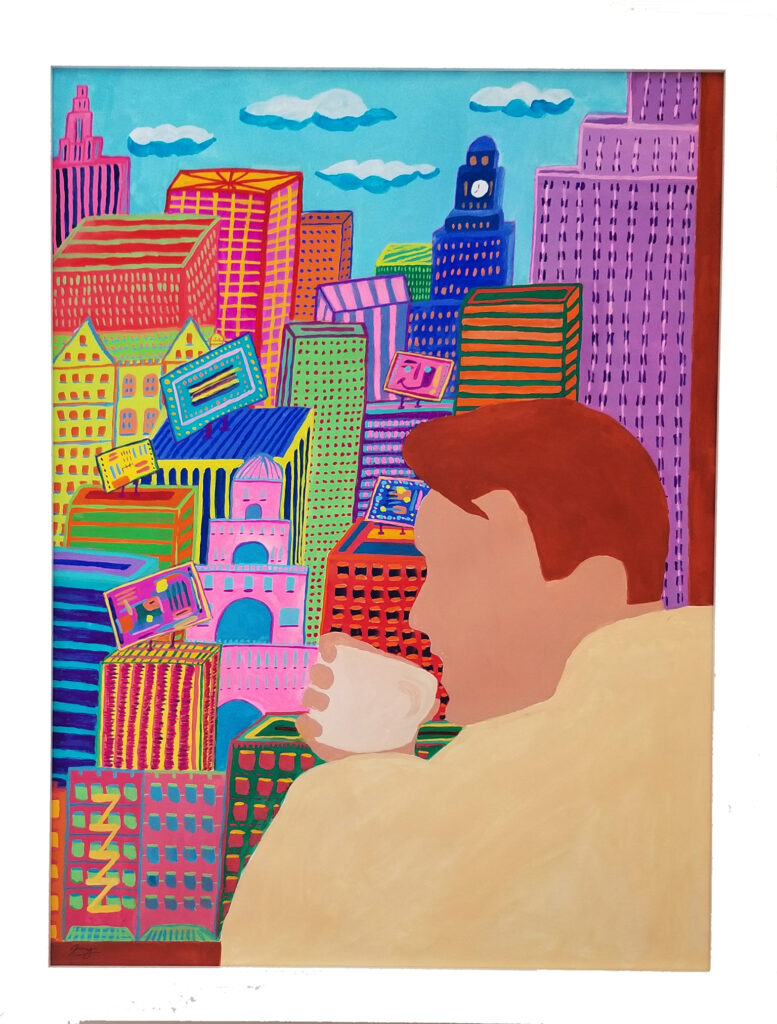

I rediscovered the framed poster again as I was moving items around in an upstairs bedroom of the farmhouse to make way for a new bookcase and more of my books from the city. I had recently been given a gift card to an art store and bought some gouache paint tubes that I wanted to try while experimenting painting on found objects, such as cardboard and paper bag scraps. The background of the original photo for the poster was not very distinct, so I decided to reinvent it with a cityscape in the manner I had used in some earlier watercolor and ink drawings. I also decided to erase the blurry chandelier in the foreground because it would always take me a confused moment of looking at it and muttering, “what the hell is that?”

I disassembled the frame and painted on top of the poster photo paper (which was adhered to a foam board). The pigment of the gouache was too transparent, so I made it more opaque. It took several layers to finally mask the black tones of the poster photo. In some places, the gouache, if I had used with any water to help spread the paint, beaded, dried and flaked off, especially on the black cocktail dress. After my first coat I added a fixative spray, but I could not prevent the poster paper and the foam board warping from moisture. In the spirit of artistic adaptation and city survival, I decided to embrace the warping, and the final painting now more fully represents the metaphorical dream of the title, “Breakfast at Tiffany’s.”

In the process of painting Audrey I realized I wanted to do a second similar image of a male Hollywood star of the same era and that might speak more to me as a gay man. I wanted something that could depict the thrill of being in such a big city and the ambition to succeed in it. I looked through posters of iconic images of James Dean, Rock Hudson, and Paul Newman before I settled on a seldom seen image of Montgomery Clift, in a pose where there is a cityscape outside a window. Audrey’s gaze is directed into the interior of Tiffany’s; Monty’s is from a smaller, personal space—an apartment.

I am not aware of any movie that Audrey Hepburn and Montgomery Clift appeared in together. The two paintings now frame a doorway that leads to a flagstone patio in my backyard and where, in the spring, I maintain a small assembly of potted flowers.

Monty

art by Jameson Currier

gouache on paper

20210211001