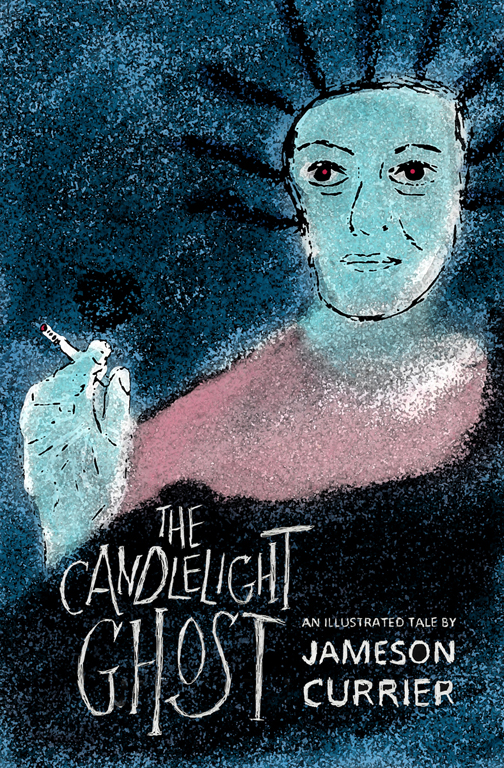

illustration by Jameson Currier

by Jameson Currier

Laughter spilled out into the lobby. Inside the ballroom, someone blew a party horn, rap-tap-tap to the rhythm of a golden-oldies pop song. While Cliff waited, he looked at himself in the mirror that filled the walls by the bank of elevators. For the first time in eight years he actually filled out his tuxedo. He was no longer tall and gaunt. He had told Jesse that he had to pull his stomach in slightly in order to button the jacket and that next time he might even have to let out the waist. Let out the waist, he repeated to himself now with a laugh. Cliff smiled and moved into the ray of an overhead spotlight. He noticed his face was round and absent of wrinkles, his neck thick and pulpy as it tightened against his shirt collar and bow tie, so fleshy, in fact, he had to lean closer to the mirror in order to detect his Adam’s apple. He pushed his hands into his pants pockets, shrugged his shoulders, drew in his cheeks and pouted, pretending he was a young model posing for a fashion layout. He felt silly but happy; here he was, an aging man acting like a kid. It was late and he still had lots of energy left. He looked away from his image when he noticed Jesse approaching.

“We can stay longer if you want,” Cliff said.

“I’ve had enough,” Jesse answered. He paused beside Cliff and struggled to get his hand through the sleeve of his overcoat.

Cliff helped him with the sleeve. They walked through the lobby, Jesse leading the way, Cliff bouncing at his heels like an animated puppy. Outside, in the sudden darkness of the sidewalk, Cliff moved ahead of Jesse, out into the street to hail a cab. None available, he noticed, as he lifted his hand into the air. They waited a few minutes, Cliff shifting back and forth on his feet as if he were still dancing.

“Aren’t you cold?” Jesse asked.

“Not really,” Cliff answered. He wasn’t wearing an overcoat. The cold air felt good. He inhaled deeply and watched his breath condense into white puffs in front of his eyes. Jesse pulled a pair of gloves out from the pockets of his coat. “Here,” he said, and handed the gloves to Cliff. “At least put these on.”

“Okay,” Cliff said. “Let’s try the subway.”

They began walking downtown. At the next intersection they stopped and Cliff looked again for a cab. Still none available. The cold air and the darkness and the city lights made Cliff giddy. Everything suddenly seemed new and shiny again. This is why I came here all those years ago, he thought, to be a part of this—this energy. Jesse waited at the curb while Cliff looked out into the street.

At the next block they headed down into the subway. Jesse moved mechanically through the turnstile and then to the platform. Cliff rocked back and forth on the heels of his feet, his movements finding the patterns of a long-ago tap class. Shift-ball-change, shift-ball-change, rap-tap-tap, Cliff’s feet went on the cement. Jesse didn’t notice Cliff’s movements. Cliff grabbed the side of a column and swung himself around like Gene Kelly would do in a musical. Jesse gave Cliff a weak smile and the two of them moved toward each other as if to kiss, but the sound of an approaching train made them pause.

When they took a seat, Cliff sensed Jesse relax. Jesse had been tense and stressed for the last month. It wasn’t the holidays so much that affected Jesse’s behavior; they had both learned to deal with those issues. It was the end-of-the-year business pressures that were eating at Jesse. Donations were down at the health-care organization where Jesse worked. The budget had been cut back. Jesse had organized that evening’s black tie benefit as a fundraiser. But costs had escalated. The hotel had upped its fee after the invitations had been printed and the advertising had started to appear. One performer canceled and another, more expensive one, had replaced her. Cliff knew that if they were lucky they might break even. He knew that Jesse believed that he had failed in his job, even though the benefit had received a good amount of media attention.

Cliff knew Jesse was worried. His job was on the line, even though no one could do better than Jesse was doing. When Cliff had first met Jesse, Jesse was working as a volunteer. Jesse worked a few hours a week as a buddy, visiting a homebound client who lived uptown. Cliff had quit a successful public relations career when he tested HIV-positive; he had taken a desk job with a home care service because he didn’t want to stay home and die. Cliff had met Jesse at a fundraiser for an organization that provided services for positive people so many years ago that he had now lost track of the anniversary date.

Jesse had casually said that evening they met that he had wanted a different job. He wanted to move up in the organization, to be involved more than as a volunteer. He wanted to work on the fundraising events and day-to-day planning. Cliff had encouraged him to apply for a position; no one would turn him down if he thought he could help. A few weeks later, Jesse went to work for the agency that had evolved from a shoestring grassroots crisis center into a multimillion-dollar corporation fighting the rising epidemic. For a while Jesse was just another guy there who dialed you on the phone, reaching you when you sat down to eat or were watching the evening news, and asked you for a contribution or about a pledge or participation in such things as a dance-a-thon or walk-a-thon. Jesse learned the ropes quickly; he had a desire to succeed and a will to live. And he had an easy going manner that translated his good looks into a charming personality. Soon, Jesse was promoted and supervising many of the people he had started with at the corporation.

Not everyone at the corporation had Jesse’s easy success. A lot of workers and volunteers had health problems. Most people could only work part-time or the days they could make it into the office. Some people showed up because the work offered them therapy. Others came as an outlet against grief. Turnover was great. Everyone wanted to help somehow even if they were frustrated by not knowing which direction they should go. Only a few were really good at raising money. Big money. Donations from other large corporations to aid the corporation with its worthy fight and mission. These were the men and women who worked with Jesse. They formed the core of the corporation’s fundraising effort. They dressed up in corporate clothes and went out on appointments. But there were also workers and volunteers who couldn’t get you to give the cause a penny.

The ones who couldn’t cut it would eventually quit. No one was ever fired or asked to resign. Guilt would work its own magic. Sometimes, someone would burn out from working too hard. Or health would intercede, illness ironically disrupting the workplace of an organization formed to combat illness. Cliff knew that Jesse took all of these losses to heart. Jesse blamed himself for not training his workers better. And he blamed himself for not raising enough money so a cure could be found or to better fund the necessary research. Eventually he got over his guilt. There were too many losses not to get over another one.

On the subway, Cliff watched a couple standing opposite him move into a kiss. The guy and the girl were both young and well dressed, dark skinned with bright white smiles. Everyone seemed so young to Cliff now. Jesse’s staff had become younger and younger over the years. The crisis had evolved even if the corporation no longer could change itself. Soon it seemed as if all of Jesse’s workers and volunteers were new to the city. Guys who had arrived in town with a diploma and were looking for their first jobs. Young, handsome, high-strung, self-absorbed guys. There was always someone to take someone’s place. The corporation had reached a high profile. There was no end of workers and volunteers wanting to sign on. And if they weren’t young and male and gay, then they were young and female or lesbian or part of another affected minority. Jesse always seemed to have an endless supply of young workers wanting to work with him.

At the benefit that evening Cliff had danced with Gordon, one of Jesse’s younger staff members. Gordon was a Southern expatriate like Cliff, which had prompted an easy bond and a friendly conversation. Gordon was just out of college and learning his way around the city. Cliff was always glad to offer advice or survival tips when they spoke. At the benefit Cliff could not keep his eyes off of Gordon as they danced. Gordon was short and well built and still had a boyish look about him. He had danced with a giddiness that infected Cliff. They had fallen into a swing style of dancing when the song changed tempos to a big band sound. When the music was done, Gordon had hugged Cliff and kissed him briefly on the lips. “Why is it that all the great guys are taken?” Gordon said to Cliff. Cliff’s eyes had widened and he smiled. Here he was, lucky to be alive decades into the epidemic, and someone still found him desirable.

Cliff thought about that hug and kiss again while riding the subway. Gordon had given him no reason to expect anything further. But there was something to Gordon that Jesse no longer possessed for Cliff. Jesse no longer made Cliff feel desirable. No longer made him feel happy and alive and healthy and needed. The truth was Cliff did not make Jesse feel desirable enough either. They had never agreed to be monogamous, but clues of Jesse’s other affairs floated to the surface without much guilt from Jesse. Cliff had been unable to respond to Gordon’s comment, as flabbergasted by its sentiment as its naïveté. Jesse had been notorious in recruiting lovers from his staff and Cliff had wondered if Gordon was anywhere on Jesse’s soon-to-be-my-new-secret-boyfriend list. Cliff had spent years overhearing hushed phone conversations late at night or stories of fabricated meetings at the last minute. At the back of Cliff’s mind was the thought the he should leave Jesse since their relationship had become platonic. But there was a history of them together that Cliff was afraid to walk away from. And the truth, the sad truth, was that Cliff had always felt the epidemic had somehow left him damaged and undesirable. Cliff had always felt defeated by his health. Who else would want him even in the small, dishonest way that Jesse needed him now?

Jesse had always felt different. Testing positive had rejuvenated Jesse’s life. Jesse had protested and demonstrated. He had gone to sex clubs and had himself pierced and tattooed. And it was Jesse who literally forced Cliff to survive when Cliff fell ill with pneumonia eight years ago. Jesse had showed up every morning in Cliff’s hospital room and had set an order to the day. The truth was, Cliff knew at the core of his being, that he had survived because of Jesse. Cliff owed his health to Jesse.

* * *

Sometimes Cliff said, quite sincerely, that he also owed his life to Max. Cliff and Jesse had been lovers for eight years; before that Jesse and Max were together for seven years. Max took care of Jesse when Jesse was hospitalized with pneumonia, nursed him back to health. Max had absorbed and rationalized the early days of the crisis and presented a model approach which Jesse could draw upon when Cliff became sick. Jesse had spent years asking about Cliff’s doctors, checking his prescriptions, reading up on treatments, planning his health. But Max had never completely disappeared from the picture. It was Max who got Jesse the job as a fundraiser. Max had been at the corporation when Jesse was a volunteer. In the last decade, Max had worked there intermittently as he battled to maintain his own health. Now, his complexion was mottled from too many medications, giving him the dark, bloodless pigmentation of a corpse. A few years back, during his angrier, more intense activist phase, Max had grown a goatee which he refused to shave for corporate appearances. Now, it grew in sparse, blotchy sections, like a stray dog’s fur matted in the rain.

“I can’t find Jesse,” Max had said when he found Cliff in the men’s room at the benefit that evening.

“I’m sure he’s checking something out for the musicians,” Cliff said.

Max walked into a stall and crumpled to the floor, his head bent over the toilet. He threw up with short gagging sounds. Cliff turned and listened to the retching. He knew Max had been fighting off gastrointestinal problems. He knew from Jesse that Max’s cocktail of prescriptions wasn’t working for him. But he had been surprised to notice Max earlier with a glass of champagne in his hand.

“This fucking medicine is like a fucking hairbrush in my stomach,” Max said. Max had years ago worked as a hairdresser.

“Do you need a doctor?” Cliff asked. He was standing behind Max, staring at the soles of Max’s black dress shoes to avoid looking at Max’s pained expression.

Max declined, waving Cliff away and mumbling something or another about insurance. But he kept complaining, bellyaching, moaning, and breathing heavily on the floor. Then he said he thought he might be hemorrhaging internally.

“Should I get help?” Cliff asked.

“Just get the fuck out of here,” Max replied.

Cliff walked away and washed his hands at the sink. He didn’t leave Max alone. Soon Max turned morose. “This is it,” he said, his fist pounding on the tile bathroom floor. “My time is up.” Cliff was trying not to pay attention, trying to casually comb his hair, waiting for Max to admit that he needed help.

“What the fuck are you hanging around for?” Max asked when he had picked himself up off the floor and had stood at the sink next to Cliff.

“I’ll take you to the doctor,” Cliff said.

Max twisted the faucets, cupped the water in his hands and washed his face. Cliff offered him a handful of paper towels.

“I’ve got to talk to Jesse,” Max said, irritably.

“He’s working,” Cliff said. “No telling where he is.”

“He’s always working,” Max said. “If he’s not working, he’s working someone.” Max threw the towels in the trash and Cliff’s eyes followed the trajectory of the paper. “I want to tell him I’m quitting. I’m moving to California. I can’t take this weather. I can’t take this shit. I’ve got to get my health back.”

“I’ll tell him for you,” Cliff said. “If you don’t find him.”

Max turned mean. “I want to tell him myself,” he said.

“Then you can tell him tomorrow.”

“This doesn’t involve you,” Max said. He was bracing his weight against the wings of the sink.

“Of course it does,” Cliff said. “Do you need a doctor now?”

A bitterness rose to the surface of Max’s expression. “Why don’t you get your own life?” he said. “Stop butting into mine. I don’t need your help.”

Max was never one to keep his opinions to himself. Over the years, he had tried to give Cliff as much advice as he had given Jesse on everything from cutlery to meditation therapies. Cliff waited at the sink, expecting Max to now offer some other off-the-wall admonition, like why didn’t Cliff go out and rent a new tuxedo instead of trying to fit into his faded, out-of-date old one. But nothing else was said. Instead, Max started to walk away before he turned back. “One day you’re not going to be so lucky,” he said.

“So I’ll deal with it,” Cliff said.

“You think just because you’re so good looking you can get away with shit,” he said. “You’re not fooling me. You’re nothing but a fucking faggot. Why are you still staying with him? You don’t owe him anything. I care about him. He’ll never mean to you what he means to me.”

Max went out of the restroom with an ungraceful tug of the doorknob. After a minute, Cliff opened the door and looked out into the hall. It was empty.

On the subway back to the apartment Jesse asked Cliff, “What happened to Max?”

Cliff simply said, “He was upset. He was drinking. He started in again about moving to California.”

* * *

Back at the apartment, Jesse tossed his jacket and shirt on the couch without hanging them up. His shoes ended up in the hall, the cuff links and bow tie made it to the top of the dresser in the bedroom.

Cliff lingered in the kitchen, his buoyancy fighting off a rising sense of melancholy. He poured himself a glass of juice and walked into the darkened living room. Jesse had done quite well with the health business. The loft they shared had a striking view of the city. Cliff looked at the buildings uptown, the windows lit and twinkling in the black air like stars in the sky. Eventually, as Cliff lifted his glass to finish his juice, he found his image reflected in the window. Such a long journey, he thought, to see himself healthy again.

Cliff finished his juice and washed the glass in the kitchen sink. On his way through the hall, Cliff stopped to pick up Jesse’s tuxedo jacket and pants to hang up in the closet. As he was slipping the pants over a hanger, something fell out of the pocket onto the floor. Cliff stooped to pick it up. It was a small gold card, the kind usually attached to a present. Cliff flipped it open and read it. “Happy New Year. Love, Ray.” Ray must be Jesse’s latest boyfriend, Cliff thought.

At the party, Cliff had seen Jesse across the room, seated at a banquette with another guy, a thin, young-looking man with a short, military haircut and an Adam’s apple too large for his neck. Across the room they looked like two children, Jesse whispering madly and the other guy with his head bent down to listen. Something about the inclination of Jesse’s head had revealed a big, wide, embarrassed grin on his face. They were seated side by side, kneecap to kneecap, a small box on Jesse’s lap, a privacy so hushed between them that it obliterated anything else in the room. Cliff, remembering that scene, could only move to the next logical point. Jesse had tilted his head back and the two of them had slipped into a kiss.

It wasn’t a brotherly kiss of thanks, or a sincere greeting, or even a friendly peck on the cheek. It was the lustful kiss of two lovers who desired to be somewhere else at that moment than where they were caught. Cliff had watched as their mouths opened to each other, the air rushed in and out, a tongue grazed against a lip and then a final, deeply felt coupling.

Cliff had been more embarrassed by the outward display of emotion than of the fact that the affection emanated from Jesse. He turned and headed out of the ballroom and into the restroom where he splashed his face with warm water and studied himself in the mirror, which was when Max had arrived.

Now, back at the apartment, Cliff washed his face again and brushed his teeth, regarding his body as if he expected it to be bruised like a piece of fruit that had tumbled to the ground. Nothing was different. His body only served as a shell for his mind, he thought. The veins of his forearms were thick and ropy from medication. Shirtless, he studied the paunch at the end of his stomach, tapped it gingerly as if he expected it to deflate like a soufflé. Cliff’s medication had restored his health and created fatty deposits at his stomach and on his back. Cliff turned sideways and studied his torso in the mirror. For a moment, before he straightened his posture, he had a vision of himself as an elderly man. Now, staring at his body, he convinced himself that the hunch wasn’t too noticeable. His doctor had said his body was unable to metabolize fat. He had high levels of cholesterol in his blood. His risk of heart attack was greater. Greater than what? Cliff had thought when he had heard that line. He was expected to have been dead years ago. Wasn’t it a trade-off anyway? Here he was, expected to be dead long ago and instead feeling like a boy who had been kissed for the first time. It didn’t make any sense.

Jesse was in bed asleep, turned on his side, facing away from Cliff’s side of the bed. Cliff sat on the edge of the bed and noticed the dust on the side of the lamp shade. Beside him Jesse did not stir. In the distance he heard a siren moving on the street below and Cliff got out of bed and went to the window. Again he caught his reflection. He smiled at himself, summoning one more time Gordon’s brief kiss. Cliff had left the restroom at the benefit after Max had disappeared and he wandered to the dance floor where he had talked and danced with Gordon. Gordon’s kiss had lifted him out of his funk, had made him feel alive instead of just being a witness to someone else’s life. Now, Cliff’s memory sifted through a history of kisses, wondering what Gordon’s might have been like if it had lingered more. Would he have opened his lips and lightly bitten Cliff’s bottom lip as they matched their breathing to each other? Or would he have allowed Cliff to slide his tongue into his mouth, slipping it around his teeth and tongue in search of the back of his throat? His nose tingled at the memory of Gordon’s cologne. Cliff felt a rise in himself. This is what lies between us, he thought, not health or the fear of losing it. This is what lies between us, he decided, the desire to be somewhere other than where we were now. The desire to keep living. To feel alive. He knew it was time for a change, even though he was reluctant—no, worried—about disrupting his status quo.

He left the window and walked out of the room and into the kitchen. He picked up the phone and dialed a number.

I’ve never been to California, Cliff thought, while he waited for an answer on the other end. He wanted things to feel new again. Things could be different in California, he decided. California could be something new for him, too.

__________

“Health” first appeared in Art & Understanding, edited by David Waggoner (Jan. 1999), pp. 30-33, 62-63, and the author’s collection Still Dancing: New and Selected Stories, published in paperback by Lethe Press in 2008 and reprinted by Chelsea Station Editions in 2011.