Illustration by Jameson Currier

IT COULD HAPPEN ANYWHERE

by Jameson Currier

Wednesday

Geoff checks his e-mail when he gets home. There is a message from his friend Jon checking on dinner next week, a message from Andrew, his college roommate who now lives in Atlanta, describing the leather crowd at the Eagle over the weekend, and plenty of spam: “Sexy, horny, barely legal teens,” “Did you get my pix?” and “Stop getting booted off line.” Nothing from Danny.

Geoff signs off the computer and goes to the kitchen. What could have changed Danny’s mind? He said he would e-mail plans for the weekend. Nothing. Nothing at all. No answer to the e-mail Geoff sent Monday. Nothing from the one he sent Tuesday.

Geoff pulls the bottle of wine he opened last night from the refrigerator. Pours himself a glass. He’ll let it go, but he can’t help be disappointed. They’ve been chatting on-line for almost a month now. Every time he plans to visit him, Danny gets cold feet. Geoff wonders if he’s being scammed. If Danny is not Danny at all but a teenage girl playing a prank, someone who lives in Utah. Or Vermont. Or Mississippi. That it’s all just a game. A disappointing game. So much for romance.

This is what he knows about Danny: He likes the country better than the city, wants to become involved in local politics, wants to meet the right guy. He took some time off after high school to get his shit together. He worked for a while at a counseling center, but quit to return to school. He’s majoring in political science. He is short (five feet, five inches), thin, blondish-brown hair, blue eyes. Wears braces. Has a cat named Chloe. Goes by the nickname DBS2020 on-line.

This is what Geoff wrote: He is an ophthalmologist. Lives in D.C. He is not as short (five feet, nine inches), not stocky but not sleek (167 pounds), a bit older (nine years more than Danny). Black hair, brown eyes. He likes movies, biking, Sinatra records. Hates the partisanship of the Capitol, and had a boyfriend for four years who wouldn’t make any kind of commitment. Wears glasses, Clark Kent style, to hide his bushy eyebrows. Figured out pretty early in life that he was gay. Goes by the nickname Eyeful.

They didn’t chat about sex. Instead, they talked about wanting relationships, needing to grow up and learn different things, what was wrong with religion today, the way it excludes gays. By the end of their first week of e-mails, Danny wrote that he was really going to like Geoff because he hadn’t hit on him. Geoff thought Danny would make a good boyfriend. They spoke on the phone twice for almost an hour each time. Danny made the calls using a phone card his mother had sent him. His voice was softer, higher, than he expected. But also more sincere. Shy. He wasn’t a girl somewhere in Utah. Or Ohio or Vermont. He wasn’t a figment of the imagination. Or a scam. Nobody would have wasted that much time trying to be honest to a stranger.

They talked about a sitcom on TV, then about skiing of all things. Geoff wanted to learn to ski. Danny said the idea of going that fast scared him. (Though he had water skied once. And liked it.)

They agreed to meet as friends. No pressure on the first date. Danny invited Geoff up for weekend. Homecoming weekend at the University where he was a student. Geoff could stay over if he wanted. On the couch. As a friend. No pressure. Just to meet one another.

Something must have scared him away. Maybe it was midterms. Maybe he’s been studying and forgotten to call. When Geoff was in college, he would disappear for hours in the basement of his dorm, incommunicado with the world in order to pass a test or finish a paper.

Geoff takes the chicken breast from the freezer and defrosts it in the microwave. Heats up the oven. Takes a sip of the wine. While the microwave is going he turns on the TV. Changes the channel to the news. He hopes the TV will distract him — he is still annoyed. He takes out the chicken, seasons it, places it in the oven.

From the refrigerator he takes out a plastic container. He breaks off pieces of lettuce. Rinses them under water in the sink. Finds the tomato and cucumber he bought over the weekend. Finds a knife, cutting board. He rinses the tomato and cucumber. He thinks how effortless it would be to cook for two. With Jerry — the guy he dated for four years — he always cooked. Liked to experiment. Now it just seems to be rote, functional. Sometimes empty.

Something makes him turn and listen to the news. Something about a University student being beaten. The name of the University catches him first, then the student’s. It can’t be the same person, he thinks.

First there is disbelief. Then he stops making the salad.

He goes back to the computer in his bedroom and logs on. He checks his e-mail messages again. There is nothing from Danny. He doesn’t log off. Or return to the salad.

He begins searching for more news.

Thursday

Walking home after work, Geoff stops at the bookstore on Connecticut Avenue, looks through the titles of the magazines in the back of the store. He picks one up, looks at photos of perfect guys with perfect dicks, replaces it in the rack. At the doorway, he looks toward the floor to see if a new issue of the free weekly newspaper is out. It is not. On the bulletin board above the stack of papers he notices a note: Candlelight Vigil, 8 p.m. He reads the name of the church. He’s walked by that building many times and never been inside. He can’t even remember the last time he was inside a church. Not since he moved to D.C., that’s for sure. On his way out of the store he thinks he wants a nap more than he wants to sit in church. He didn’t sleep well the night before, the news too disturbing. He kept playing the details over and over. College boy beaten and left to die. It couldn’t be the same guy. It couldn’t be Danny. That Danny. This had happened to someone else. Geoff was not a part of this.

At home Geoff places his briefcase on the table, lies down on the couch without taking off his shoes or clothes. He doesn’t even loosen his tie. Only the glasses come off. Plop, on the coffee table. The day has exhausted him. It’s been harder to concentrate. He had more patients than he expected.

He thinks about turning on the TV but he can’t bear the sound. Or any more news. All day long he has chased the updates. Was Danny still in a coma? Was anyone arrested? How did the beating happen? Who found Danny’s body?

He closes his eyes and falls asleep. He doesn’t dream. It is a deep, blank sleep. When he wakes he notices it is a quarter past seven. He looks out the window behind the couch. Notices it is dark. His head is cloudy, thick, in spite of feeling rested. Weight has settled into his shoulders. He stands and steadies himself. Walks to the kitchen, pours himself a glass of water.

He looks at his watch. He thinks he could make it. It would be good for him to be out. He takes off his coat and tie, throws them on the back of a chair. He rinses his face at the sink, takes a sweater from the closet, finds a jacket. In front of the mirror he squints to clear the hardness from his face. Runs his hands through his hair. Cleans his glasses. Then heads out the door.

At the church, they are passing out small, white candles and paper reflectors at the entrance. He takes one and walks down the aisle, not too far, chooses a pew in the back. There are maybe fifty people seated in the church, but more are finding their way inside. The church is full of arches, thick, white candles on an altar of dark, carved wood. A blood red carpet covers the floor. Stained glass windows of New Testament scenes line the sides. An organist is playing, the windy sound filling the room. It is too much church for him. But if prayer can help, then prayer is what he will do.

Geoff looks through a hymn book while he waits for the service to begin. He thinks about the time before he was gay — before he identified himself as gay — the way even the thought of a man could disturb him — the dilated iris, the quickened heartbeat, the trace of sweat — all because of an attraction. A surge of confusion and lust. The bent of his desire had bitten him in his late teens. He wonders if it was easier then — the not accepting of himself. He wonders if because he now admits that he is gay that he is also more afraid of being alone.

The row he sits in fills up with men. A few wiggle out of their coats when they are seated. Someone stands up, fold his jacket, places it on his lap. He senses individuals and colors. Some like blue. Others brown. Short, buzzed cropped hair still in fashion.

There are hymns and prayers, kneeling and standing, voices singing, the organ drowning out all sound. Geoff’s mind wanders to the windows during the reading of scriptures. Fake daylight comes from behind each pane. More dust than color.

Towards the end of the service, ushers stand in the center aisle, light the candles of those seated at the end of the pew. Flames are passed from person to person. A hunky guy in a flannel shirt passes the light to Geoff. Geoff passes it to a woman on his left. The chandelier lights are dimmed. Another prayer is said; another hymn is sung. The candles are blown out. The service ends.

Geoff follows the hunky guy in the flannel shirt down the main aisle toward the exit. He waits his turn to return his extinguished candle to a box. He is disappointed in the service. He has not reached any kind of internal resolution. He doesn’t feel better. But he doesn’t feel worse. He feels incomplete. Something remains unfinished.

He notices a bright light as he heads through the lobby to the large wooden doors of the exit. The hunky fellow in the flannel shirt is now wearing a quilted vest. Yellow. They are side by side at one point, waiting to leave the church. The guy gives Geoff a smile. Geoff returns it, hears someone ahead say, “You can’t just do that. This is not a place for that.” On the steps, a camera crew is filming people exiting the church. Instead of taking the front exit, Geoff heads for a side door. The hunky guy does the same. They are again side by side, both waiting to exit.

“I’m Steve,” the guy says, nodding and smiling again to him.

Geoff smiles, says his name.

“You’re a friend of Jon’s, aren’t you?” Steve asks. “I think I’ve seen you at the gym.”

“Yes,” he answers. “I thought you looked familiar, too.”

Steve has a pretty face: full lips, pale skin, wide eyes, small ears. He’d be too pretty were it not for receding hairline, heavy Adam’s apple, obvious drop-dead body. And the voice. Deep, nasal, full of hormones. Cuts right through to the chest. That’s what makes him more hunky, Geoff thinks. That voice. Geoff keeps him talking.

They talk about the service as they wait to exit. Geoff reaches the stairs outside first, slows his walk so that Steve can catch up. He doesn’t know why he does it. It is cold out. Breath condenses into white air. Geoff thinks Steve will vanish the moment they reach the street, thinks he is part of the group of guys who were seated in his row and who will head their own way once they regroup on the sidewalk. Instead, Steve walks with him up the sidewalk toward the street corner. They talk some more. About whether the college boy will live. Steve’s voice hits Geoff’s ribs, swirls around in his lungs, makes him too giddy for such a serious subject.

But Geoff does not confess his friendship with Danny. It’s not that he wants to keep it secret. He’s not ready to admit it’s the same guy. Or ready to admit that if it isn’t, once again, he’s been dumped. Or duped.

Steve says some nights in this neighborhood it can be pretty rough — teenagers driving by, throwing bottles. “That’s what you get living in the ghetto,” he says.

“And a pricey one at that,” Geoff adds.

They talk some more about the way real estate prices have gotten higher, about the favorite neighborhood restaurant a block away that went out of business when the landlord tripled the rent. Then there is a break in conversation. A point where the subject should change but they are both aware they are still standing together at the corner.

“I’m parked over there,” Steve says.

Geoff looks over Steve’s shoulder, into the dark.

“You want to get together for dinner some time?” Steve asks.

“Sure,” Geoff answers. “What’s your schedule like?”

“What about tomorrow?” Steve asks. “Are you free tomorrow?”

Geoff wants to respond that he’s been free for quite a while, but he answers, instead, “That sounds good.”

They exchange phone numbers. Geoff has a pen in his coat pocket. Steve has the program from the vigil folded in his back pocket.

Friday

They meet for dinner outside the restaurant. Steve is there first. They shake hands, take seats, order drinks from a waiter. The restaurant is a series of small rooms with small tables. There are candles lit on each table. Geoff thinks Steve is more attractive than the waiter. Steve is wearing a black sweater, clingy, makes his face look younger, his body intimidating. Geoff wears cologne, not his usual scent. Something different. He wants this to work.

They talk about the college boy. He is still in a coma. The suspects were arraigned this morning. Geoff has heard that there is another vigil at the University this evening. And another one in town at a different church. They swap details that they know or have heard since yesterday. Geoff says that the two guys were connected to another beating, which is how they were caught. Steve has heard that there will be a protest — a minister told a reporter he was just waiting for the gay boy to die and go to Hell.

The restaurant is Italian. Steve orders penne. Geoff orders a chicken dish, even though he knows it’s something he could prepare on his own. He feels light-headed from the wine he ordered. But happy. (And silently guilty.) Steve keeps the conversation moving, talking about his job drafting blueprints for an architect.

This is what Geoff knows about Steve (from Jon, his friend, on the phone, earlier in the day): Steve hasn’t had a steady boyfriend in over three years. (His mother died; his brother tested positive; his dates find him too needy.) He’s sexy but dull. Obsessive about his body. (His legs are in great shape; his waist is under thirty.)

After dinner they decide to see a movie. They ride in Steve’s car, a Honda Accord, to a mall where a multiplex cinema is located. Geoff is still light-headed, ready to be affectionate. He wants to kiss Steve but holds back. They park the car, walk inside the mall, window shop for a few minutes, buy tickets at the booth. Dutch. They take seats together in a back row. When the light goes down, Steve reaches for Geoff’s hand. This surprises Geoff; he adjusts his posture so that he is comfortable.

The movie doesn’t entertain Geoff. It is a satire about a Utopian community under a bubble. He finds the laughs forced. His mind drifts elsewhere — to Steve’s hand, to the details of the college boy, to a patient who hasn’t paid his bill. At one point he breaks into a sweat. His breathing becomes forced. He thinks something is wrong but he doesn’t leave. The moment passes. The movie ends.

After the movie they walk back to Steve’s car. Steve asks Geoff if he wants to come over to his apartment for a drink. Geoff understands it is an invitation for sex. He breaks out into a light sweat again.

“This is always awkward,” Steve says. He has stopped by the car door. Passenger side. Next to Geoff. “I can’t do this without being honest. You should know I’m positive.” He casts his eyes to the ground and then rapidly adds. “I’m not sick or anything.”

The news is unexpected, takes Geoff by surprise. His first response is to tell Steve that he is not the first guy he’s slept with. Positive or otherwise. But Geoff holds the thought back, thinks it would sound crummy, impersonal. Instead, he answers, “It’s okay.” He keeps the moment simple. Then Geoff reaches up and presses his hand against Steve’s neck. Their eyes meet. Steve reaches around him and unlocks the car door.

Steve parallel parks a block away from his building. They walk together down the street. It is dark, leafy, idyllic. As cold as the night before. Steve lives on the fourth floor. They ride in the elevator standing in separate corners.

They begin kissing as soon as Steve unlocks the door. Geoff feels rushed, anxious, but he slows himself, running his hands along Steve’s back. Steve presses forward, lifts the ends of Geoff’s shirt out of his pants, slips his hands beneath Geoff’s shirt, along his chest. The touch of his skin makes Geoff gasp, but he continues kissing, breathing, holding Steve.

Steve breaks away, takes Geoff by the hand. They walk through the apartment. Geoff glimpses details: a framed poster of a lighthouse, a bookcase with seashells. They stop in the bedroom and kiss again at the foot of the bed.

Geoff lifts the edges of Steve’s shirt out of his pants. He runs his fingers along Steve’s skin. There is a coolness to the bedroom. They close in for warmth. Geoff finds Steve’s muscles shaping his grip. Steve breaks away, smiles, sits on the edge of the bed, unlaces his boots. Geoff sits beside him, unties his shoes, takes off his glasses, places them on the windowsill.

Before they kiss again, Steve helps Geoff take his shirt off. He tosses it toward a chair. It misses, lands on the floor. He laughs, says “sorry,” the voice playful. Steve takes his own shirt off, tosses it toward the chair. It lands a little further into the room, still misses the chair.

They draw together again and begin kissing. They shift their weight so that they are now lying on the bed. Steve positions Geoff on his back, lies above him. He breaks away this time to help Geoff remove his pants. They land on the floor, the belt buckle thunks against the wood floor. Steve takes off his jeans. Geoff doesn’t hear the sound they make. They are again against each other. Both in underwear. Kissing, feeling each other.

At points they giggle, laugh like boys. At other times they are serious, gasping, moaning. They both reach orgasms twice, separated by moments of lying in each others’ arms. Everything is kept safe.

Geoff has forgotten about Danny until he rises out of the bed to dress.

“Do you want to stay?” Steve asks. His voice is level, not needy. An easy invitation to continue. The room is full of intimacy. Deep, like a pool.

“I have patients tomorrow morning,” Geoff says. “Otherwise I would.”

Steve watches Geoff dress. Geoff moves like a shadow through the room, lifting off clothing from the floor, holding them toward the light that drifts into the room from another place. “Want me to turn on the light?” Steve asks.

Geoff shakes his head, “No.” “This is fine,” he says. When he is dressed he sits on the edge of the bed, kisses Steve again.

“Want me to drive you back?” Steve asks.

“I’m just a few blocks away,” Geoff answers. “Will I see you again?” he asks.

“Sure,” Steve answers. He bows his head to his chest, his smile slips up toward his ears. “I’d like that.”

“What are you doing tomorrow night?” Geoff asks. He regrets the question the moment it is out there, in the room, waiting for an answer. Makes him seem too needy himself.

“Getting together with you,” Steve answers.

It is smooth. This feeling. Geoff likes it as much as Steve does. They kiss again. Geoff lets himself out of Steve’s apartment. He takes the walk back to his apartment slowly. The sounds of his footsteps echo back romantically.

Confusion surfaces when he unlocks his own door. He boots up his computer, checks his e-mail messages. Nothing from Danny. He logs off, walks into the den. He turns on the television and lies down on the couch. This is how the news will come to him.

Saturday

He confesses over dinner. Not at first. First, Geoff listens to how Steve spent his day — the morning trip to the gym, the afternoon search for a replacement bulb for his grandmother’s chandelier. Then Geoff describes two patients he saw. A man in his fifties with a toupee. And a woman with a facelift wanting information on laser surgery. Something he wouldn’t advise her to consider.

Steve takes over the conversation. He talks about his younger brother, who also tested positive last year. “It was a big wake up call,” Steve says. “For both of us. We were big party boys. We thought it was neat that we were brothers and both gay.”

Steve talks about how he’s changed since then. If he goes to a club he won’t do drugs. Usually leaves early. Geoff says he goes to a bar maybe once every two months. “I end up just getting drunk,” Geoff says. “It’s wasted time. I don’t like having a hangover the next day.”

While they are waiting for the check, Geoff says, “There’s something I should tell you.” He watches Steve’s eyes widen, ready for the worst case. “It’s something strange. Not strange, but it’s left me feeling odd. I’ve been chatting with a guy on the Internet for almost two months. I met him on-line on a Saturday morning. His name was Danny and he was a college student.”

Steve relaxes his posture but his expression takes on one of amazement. He asks, “Did you meet him?”

“No,” Geoff answers. “We talked on the phone twice. He sounded like a nice guy. We made a date to meet this weekend. To go to a homecoming football game at his school. I was going to drive out there. He was supposed to e-mail me at the beginning of the week — to send me details on where to meet him.”

“And they never came,” Steve says.

“It could be that he just got cold feet, and is blowing me off,” Geoff says.

Steve doesn’t answer quickly now. He lets the details sink in. “Did he send you his picture?”

Geoff nods, answers, “Yes.”

“Is it the same guy?” Steve asks.

Geoff nods, answers, “I think so. I can’t be certain. I never got his last name. Or his phone number. He called me.”

Steve’s hands rest on the table, his eyes cast downward. “I had a guy keep blowing me off that way about a year ago,” Steve says. “He’d find me on line and chat and say to meet him at so-and-so and then never show up. It was frustrating. I finally just put a block on him. I know how you feel. Even though this sounds too weird of a coincidence.”

“I’m not certain what I should do,” Geoff says. “When I got home last night, there it was, on the news. The parents. The statement from the hospital about his death. It’s just I feel I should tell someone it happened — or didn’t quite happen, so I don’t think I made it all up.”

“I understand,” Steve says. He offers a little laugh, to lighten the mood. “They’re turning him into a saint. The media, the activists. Every mother’s son. The boy next door. The new American tragedy. It could drive you crazy with all the wondering. The what if. What if that was the guy I was supposed to go out on a date with. Or worse. What if it were me.”

“I don’t know, I feel like I’ve failed some kind of test,” Geoff says. “Like I wasn’t there for him. Like I should have been there.”

“If it was him,” Steve says.

“If it was him,” Geoff agrees. He laughs and tries to lighten his own dark mood. “But according to some people we are going to rot in Hell, you know.”

“Eternity in Hell,” Steve answers. “They already have our names stitched in the uniforms.”

“I thought about contacting the police,” Geoff says. “But what do I tell them? That I got e-mails from someone who might have been Danny?”

“Just bypass the police and go directly to the press,” Steve says. “It looks like what everyone else is doing. Anyone who ever had a class with him. Or who petted his cat. Or stood next to him in line.”

“It makes it seem like a game,” Geoff says. “But it’s not.”

The waiter brings the bill to the table. They split the check evenly. They put on their coats and walk out to the parking lot. It is colder than the night before. Their steps are faster.

Later, in bed, in a more intimate position, Geoff struggles with his comfort. Had this not happened to Danny, Geoff would not have met Steve. “It doesn’t scare me at all,” Geoff says. “It should. It could happen right here. In this neighborhood, too. It just seems so unreal because it’s too close to home. But I’m not afraid. I can’t let myself be afraid.”

“There was a piece on the news today how people are leaving flowers at the site where they found his body,” Steve says. “A fence. A wooden fence in front of a deserted field. I heard someone at the gym talking about driving out there. The funeral’s tomorrow morning.”

Geoff presses his lips against Steve’s chest, kisses the skin, breaks away, kisses again. “Why would he do that?” Geoff asks. “Drive out there? For someone he didn’t know.”

“Because it happened,” Steve says. “This could have happened anywhere. It could have been any one of us.”

________

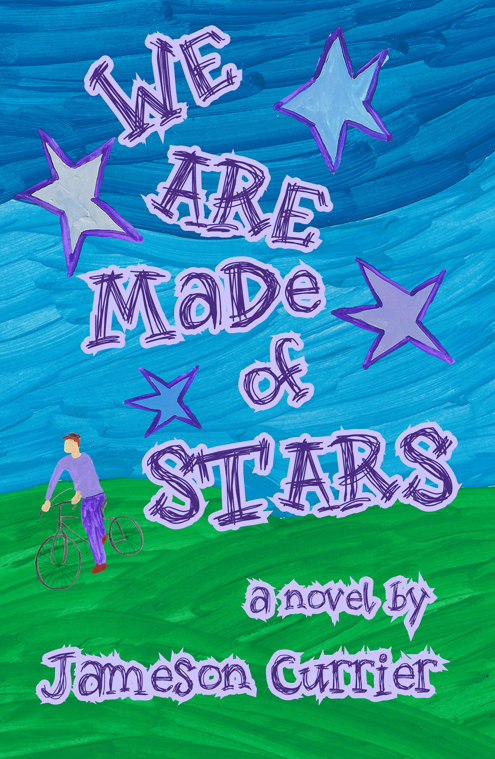

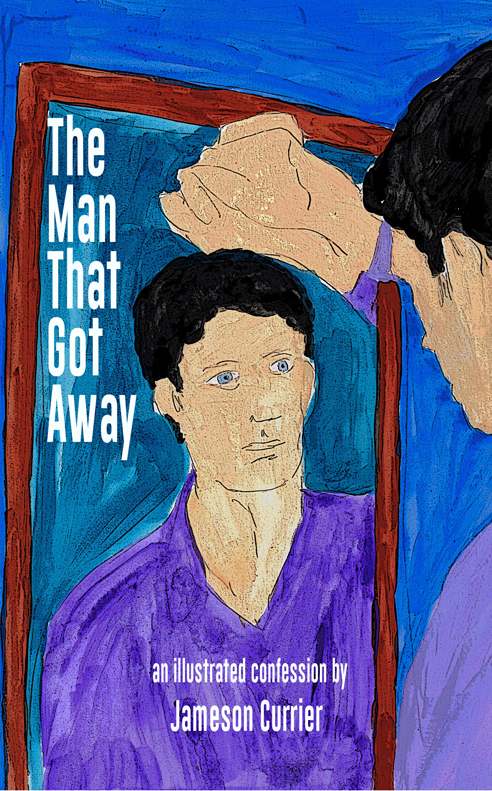

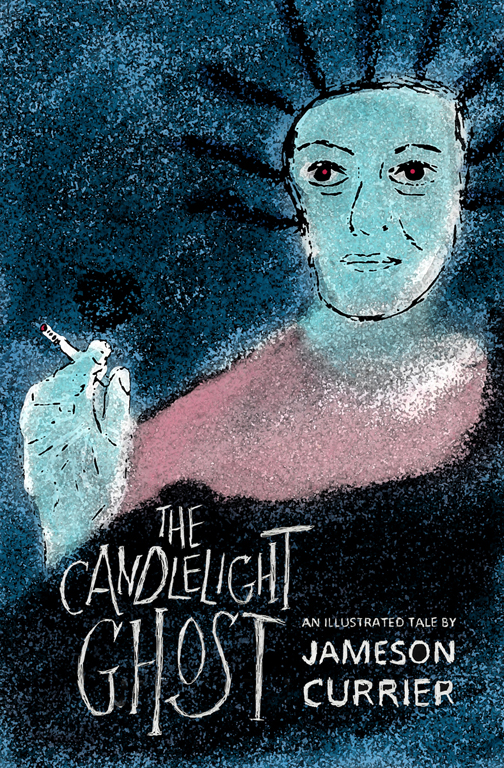

“It Could Happen Anywhere,” an excerpt from A Gathering Storm by Jameson Currier, first appeared online in Chelsea Station Magazine on October 9, 2014.

A Gathering Storm by Jameson Currier was published by Chelsea Station Editions in 2014. It was a Lambda Literary finalist for Gay Mystery.