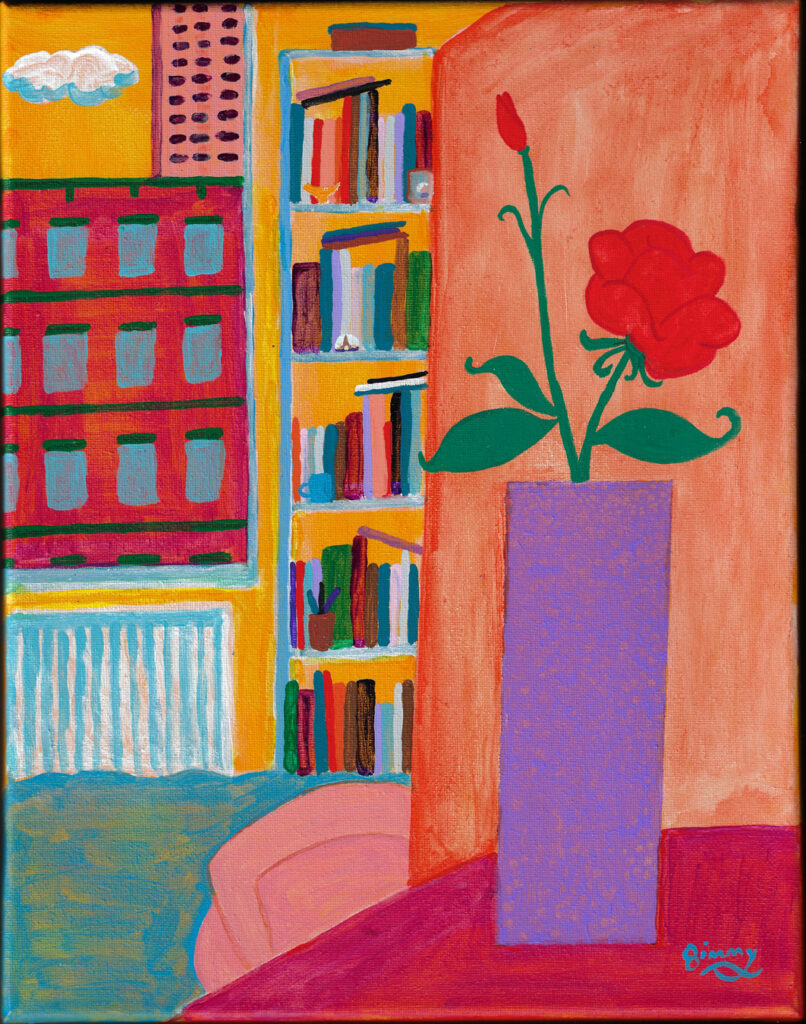

The Chelsea Rose

art by Jameson Currier

acrylic on canvas

20241121001

This article was originally published on Chelsea Station on May 26, 2014.

New York Stories

Recommended Reading by Jameson Currier

The HBO production of Larry Kramer’s play, The Normal Heart, has revived interest in the early years of the AIDS epidemic.

Kramer’s play, which debuted in 1985, was one of the first literary responses to the epidemic. The theater community was quick to assemble and produce plays which provided messages and information for a call to action. Early plays such as As Is by William Hoffman and Safe Sex by Harvey Fierstein are good examples.

Gay men were among the first to write about AIDS, though any gay man will tell you, emphatically, that AIDS is not a gay disease. It is, however, an important part of gay history. Traditionally gay men, particularly young gay men still struggling with their sexual identity, have looked to gay writers as guides or for verification of their self-perception; the writings of Tennessee Williams, Truman Capote, James Baldwin, and John Rechy are good examples for my generation of men. And in the early years of the AIDS epidemic this was no different. We looked to journalists, playwrights, poets, and novelists to attempt to understand what was going on.

One of the initial purposes of writing about AIDS was to convince readers that the disease, and the threat of it, existed. Who could predict that a virus lurked in our bodies for years, reversing the natural order of things, young men dying before their time? Another reason was to dispel the stigma attached to the disease—that AIDS was not strictly a gay disease, that what was happening was happening to human beings, not to suspected deviates or sinners, that AIDS affected all people regardless of sexual orientation and practices. In responding to the lack of drugs and services from the medical community and any sort of response from local and national governments and agencies, AIDS produced a powerful voice for the gay community within the political landscape that it may never have been able to achieve otherwise.

As the gay community has become more visible and accepted through an increased media exposure and cultural acceptance, and as protease inhibitors and other drugs have made HIV manageable, many of the lives and stories of the early years of the AIDS epidemic have been forgotten. The following books are a suggested reading list of AIDS-themed literature. It is neither comprehensive nor exhaustive, but is compiled from books I read, reviewed or wrote during or about these years. In the United States, the main epicenters of AIDS were San Francisco, Los Angeles, and New York, and the focus of this list is to recognize those stories set primarily in New York City, since this is the place I have called my home for more than thirty-six years.

Ground Zero (1988) and Chronicle of a Plague, Revisited (2008) by Andrew Holleran.

Andrew Holleran was a successful novelist in 1980 when he began writing a column for the magazine Christopher Street, the gay literary equivalent of The New Yorker. The column, “New York Notebook,” was about the latest thrills and lesser issues of urban gay life—dinner parties with friends, dance clubs and their music tracks, Greek statues on display at the Met or the Getty, and the loneliness one feels at the holidays. Holleran had a strong sense of character, a good ear for pithy dialogue, a focused concentration for theme and metaphor, and a lush prose style that served him well, and when the AIDS epidemic arrived Holleran continued to write about the minutiae of gay life, only now his themes and details swirled around bolder issues: illness, fear, anxiety, death, and grief. By 1986 Holleran admited that he was writing two kinds of essays: descriptions of New York City as a cemetery and elegies for friends. Ground Zero, first published in 1988, collected 23 of these essays. It was a bleak, harrowing, and important look at the impact of early years of the AIDS epidemic on the intersecting circles of gay men, particularly the more upscale ones in Manhattan and Fire Island. Holleran wrote of visits to hospitals to see sick friends, attending funerals, memorials, and wakes, and discovering his present-day life as a sequence of memories. And Holleran captured best what many other gay writers seemed to ignore or avoid when writing about the plague (if they wrote about it at all)—the fear and the denial of the times. He also depicted a gay metropolis at change: unruly, nervous, frightened, suspicious, and angry. Still, what rose to the surface of those grim, beautifully-executed essays was his firm portrayal of gay men and their friendships and how important they were to each other in the course of these trying and uncertain times. Now out of print, Holleran reassembled his essays in 2008 into Chronicle of a Plague, Revisited: AIDS and Its Aftermath. I am a great admirer of the contents of both editions of Holleran’s essays, as I was when they originally appeared in Christopher Street and other publications, and I am grateful to the impact of them on my own life in the city and my thinking and writing about the epidemic. Holleran is one of the most vital and distinct voices in gay literature, and to me, these essays represent a point of view of what was happening during the early years of AIDS, even if Holleran, like many of us “worried well,” only arrived at the conclusion that nothing about the epidemic made any sense at all. Also recommended:In September, the Light Changes, Holleran’s short story collection, many of which deal with the impact of AIDS on the circles of friends in New York.

Eighty-Sixed (1989) by David B. Feinberg and What I Did Wrong (2007) by John Weir.

Back in the mid-1980s David Feinberg and I were in a writing group together when he learned of his HIV-positive status and I had the chance to read the early versions of his manuscript of his first novel, Eighty-Sixed, as he was writing it, about an urban gay man’s lovers and friends pre-AIDS and post-AIDS, embellished with David’s biting humor and irony. Eighty-Sixed contrasts the life of BJ Rosenthal, a gay man living in the New York City neighborhood of “Hell’s Kitchenette,” before and after the advent of the AIDS epidemic. In 1980, BJ’s greatest concern is finding a boyfriend or satisfying his libido. In 1986, every potential liaison is laced with cynicism. As grim as living in the shadow of death becomes, BJ never loses his sense of humor. Anyone wanting to get a sample of David’s wicked and insightful wit should start here, but equally as good are his subsequent stories and essays that can be found in Spontaneous Combustion (1991) and Queer and Loathing (1993), even as they progressively become sharper and angrier as David’s health deteriorated due to AIDS. The year that David published Eighty-Sixed, John Weir published his debut novel, The Irreversible Decline of Eddie Socket, about a young man who becomes involved in a loveless relationship and learns that he has AIDS. Eddie was a slacker before the term was coined, out but not necessarily proud, and Eddie and his journey are hardly a somber read. It’s as humorous as it is harrowing. I remember David telling me of meeting John and the giddiness in his voice at finding a kindred soul and someone who could be as wickedly funny as he could. The two authors went on to become best friends. Both authors were active members of ACT UP. David’s death in 1994 at the age of thirty-seven left a deep wound in all of his surviving friends. I also highly recommend John Weir’s novel, What I Did Wrong, published in 2007. What I Did Wrong captures David with uncanny precision in the character of Zack, but it also vividly captured the narrator Tom’s grief and imbalance following Zack’s death. Tom’s “lost boy adrift” sort of life mirrors the lasting affect that AIDS has had on friends and survivors of the gay men who died of the disease—in a way that doesn’t go away with aging and the passing of years. This is also a deeply felt book about having a New York relationship and the experiences of a certain generation living in the city, in the same way that Breakfast at Tiffany’s or Bright Lights, Big City or Slaves of New York are about New York experiences. This was a profoundly good and satisfying read for me; in many passages of this novel Weir’s prose is stellar and lush, particularly in its last, glorious paragraphs.

The Body and Its Dangers (1991) by Allen Barnett

It is always hard for me to pick a favorite story in Allen Barnett’s collection The Body and Its Dangers. The most anthologized story, however, is “The Times as It Knows Us,” and it is this story for the book’s inclusion on this list. “The Times As It Knows Us” takes place in July 1987 and is set at a summer house in the Pines on Fire Island. The story revolves around seven housemates discussing articles in The New York Times. The first is a debate over a lifestyle article about the impact of AIDS on a Fire Island household. The next debate revolves around the obituaries listed in the paper’s Saturday edition, as the housemates fill in information which has been omitted from the death notices, such as the cause of death. What is seldom discussed here, as in the case of Feinberg and Weir, is how life events helped shaped talent. Barnett in died in 1991 at the age of thirty-six of AIDS-related causes.

Dancing on the Moon (1993) and Still Dancing (2007) by Jameson Currier.

I arrived in New York in the summer of 1978 after graduating college and lived in a small and expensive apartment in the West Village that I could barely afford. In my early years in Manhattan, I worked as a telephone operator, a legal proofreader, and an entertainment publicist, sometimes all in the same day. Many of my early AIDS stories were inspired from my experiences with my friend Kevin Patterson when he became ill with AIDS. Kevin was a playwright (A Most Secret War) and a theater publicist (he worked at the Public Theater for many years). “Winter Coats,” the story in the collection about two friends shopping for a winter coat—one who is struggling with AIDS—was written after an outing with Kevin. The tale of the two friends with AIDS sharing an impromptu cab ride around Manhattan in “Reunions” was a story I pieced together while I was with friends at a diner on Ninth Avenue after Kevin’s memorial service. The details of “What They Carried” are drawn from my actual experiences while caring for Kevin when he became ill with AIDS—the overwhelming things I and his other friends physically carried to and from his hospital room and his apartment in his final days. In the process, we created our own community, network, family, and support group. This story was written during the week following Kevin’s death as part of my grieving process. It is one of the most truthful stories I have ever written, and is as close to being nonfiction as it is fiction. I always approached this story as a sort of personal therapy and a story I had to tell, not a story that would ever be published. Even though I wrote this story when I was thirty-two years old, it is still the story of a “young man.” At the time, I had only had published two short stories with gay themes and a handful of essays on being gay—and felt I was still learning how to write fiction. My early AIDS stories were published in Dancing on the Moon thanks to my friendship with David Feinberg, who showed my stories to his editor, Ed Iwanicki, at Viking. Still Dancing, published in 2008,collected twenty of my short stories about the impact of AIDS on the gay community written over three decades. Ten were from Dancing on the Moon and ten were more recently written, and for Still Dancing I chose stories that revolved around gay New Yorkers—those lost, those surviving, those displaced, those undaunted, and those who became expatriates. My friendship with David is also reflected in the story “The Chelsea Rose,” which opens Still Dancing, though David and I never lived in the same building. “The Chelsea Rose,” along with “Manhattan Transfer,” is one of the more recently written stories in the new collection, about the history of the inhabitants of a Chelsea apartment building, depicting the migratory path of its residents and the deep devastation the epidemic left on a generation of gay men. “The Chelsea Rose” begins in the late 70s, just as I did in Manhattan. “Manhattan Transfer” takes one of the marginal characters in “The Chelsea Rose” and focuses on him twenty-five years later, as he grapples with surviving the epidemic, being HIV-positive, and looking to give a new meaning to his life.

Such Times (1993) by Christopher Coe

One of my first book review assignments was reviewing Christopher Coe’s second novel, Such Times for the Washington Blade. Coe’s first novel, I Look Divine, published in 1987, was the witty and luminous portrait of a wealthy, intelligent, narcissistic man who believed he was exceptional from the moment of his birth. Shuttling across the affluent, au courant landscapes of Rome, Madrid, Mexico, and Manhattan, I Look Divine recounted the tragedy of Nicholas, the “divine” creature of the title, and his downfall from his obsessive self-love. As narrated by his older brother in a cleverly succinct manner, Nicholas’s life was stylish and divine right up to its end. That same style to life reappears in Coe’s second novel, Such Times, published in 1993, but the journey on which the author propels his characters this time is through the bleak and haunting realities of AIDS. This time Coe slowly strips his narrator, Timothy Springer, of his wealth, health, and good looks, and, in the process, infuses this novel with a humanity that was often absent from I Look Divine; Such Times becomes, then, a Job-like story that resonates for anyone who faced the demands of AIDS. But like I Look Divine, Coe tells his tragic tale in that same great, grand, gay, witty, and wonderful way. Such Times pulsates with the confusions and heartbreaks of gay relationships—from the uninhibited and disposable to those hopeful and unrequited. Anyone who has found himself as the third party in a triangular relationship, will certainly empathize with the pleasures and pains Timothy finds in his love for Jasper. And anyone who has witnessed the changes of gay life during the first decades of the AIDS epidemic, will find Such Times a must read; Coe covers a multitude of subjects, from fisting to taking the HIV test. Coe spends as much energy pondering science and medicine and health as he does on sex and gay men and relationships. There are scenes of lumbar tests, tales of hospitals overcharging patients, and explanations of the thymus gland. In lesser hands, this sort of diversion could potentially bog down a contemporary novel, but throughout Coe is able to maintain Timothy’s cleverness, particularly on a section about retroviruses. In attempting to explain nucleotides to Jasper, for instance, Timothy conjures up a metaphor of precious stones. “My virus may begin with an emerald, and then go: diamond, diamond, sapphire, ruby, emerald, emerald, ruby. Your virus may begin with a sapphire, and if read from end to end, which they can do now in a laboratory, it might go something like this: sapphire, diamond, diamond, sapphire, ruby, emerald, diamond, ruby, ruby.” Christopher Coe died shortly before the paperback publication of Such Times, on September 6, 1994, at his home in Manhattan. He was forty-one years old.

Diary of a Lost Boy (1994) by Harry Kondoleon

On a book tour for Dancing on the Moon, a reporter asked me if my stories could be read and appreciated by people unfamiliar with gay life and AIDS. I answered that AIDS fiction summons up the greatest themes in literature, among them sex and death and faith, themes that are universal and prominent in every life. Anyone who has lost a loved one from death, untimely or natural, can read AIDS fiction and understand the emotions it forces into place, anyone who has acted as a carepartner for someone who has been ill will understand the compassion necessary in tending the sick, anyone facing death from a life-threatening illness should be able to find strength and companionship in AIDS writing, anyone interested in uncovering the heart of the human soul should read writing about AIDS. It is always surprising when a writer has the ability to infuse such weighty material with a comic touch; even more surprising when it is accomplished with the dexterity that playwright Harry Kondoleon did in his only novel, Diary of a Lost Boy. Hector Diaz, Kondoleon’s thirtysomething gay narrator, has been told by his doctor he has two years to live. “Sex is a memory, eating is a drag,” Hector states about his life, and to extricate himself from his own tragic reality he immerses himself in the trendy lives and marriage of his closest friends, Susan and Bill Ded. Hector, having originally introduced Susan to Bill, feels an obligation to either save the crumbing marriage or help each of his friends individually survive the destruction of their union. In this capacity, he becomes a confidant and companion to both parties, for instance accompanying Bill to a Philandering Husbands Support Group and chaperoning Susan on her first blind date following their separation. Episodic in construction, Diary of a Lost Boy is Hector’s interior monologue over the course of a year. As Susan and Bill’s marriage unravels, so does the state of Hector’s health. “I got my latest T-cell count,” he says. “You all know by this point what that is—a kind of sports record of how your immune system is doing during your last inning.” Though his health is faltering slowly and unfortunately to the forces of disease, Hector’s mind remains razor sharp even as it approaches dementia. In fact, one of the strengths of Kondoleon’s writing is his ability to focus so clearly on the lunacy that surrounds Hector, allowing, at times, the reader to forget the narrator is even ill. Kondoleon died of AIDS-related complications in March, 1994 at the age of thirty-nine.

The Farewell Symphony (1997) by Edmund White

“The writer’s vanity holds that everything that happens to him is `material,’” Edmund White explained in The Farewell Symphony, a sentiment that echoes strongly throughout this third and final installment of an autobiographically inspired trilogy that began with publication of the novels A Boy’s Own Story in 1983 and The Beautiful Room Is Empty in 1988. White’s unnamed narrator, a man driven by “twin appetites for sex and success,” is a struggling writer and a gay man who recalls the personal and professional events of his life over almost three decades and across a variety of American and European locales, from the hedonistic back-room bars of Manhattan in the 1970s to the more sedate literary salons of Paris in the 1980s.. White is a master of carefully layered descriptive passages, and he uses these to great effect in charting his narrator’s early journalistic career on a Manhattan magazine, his writing sabbatical in Rome, and the generous patronage he receives from a noted elderly writer and “man of letters” whom he meets at a gay bar. The strength of The Farewell Symphony, however, lies in the enormous cast of characters White has assembled, all finely detailed as well, from a female co-worker whose “cheekbones were dusted with a blonde down” and whose father was a Nazi officer, to the narrator’s own grandmother, who “could read only by moving her lips.” White also creates a rich assortment of gay male characters, from a Broadway actor with a “face too strong and ironic to go with the waifish role he liked to play,” to a roommate who “resembled an old, friendly dog that comes padding up to you.” At the core of all this remembrance, however, is the depiction of gay life during a more liberated consciousness in the years before the arrival of AIDS. Mr. White clearly delineates how this generation of gay men patterned their relationships so differently from heterosexual ones, how some one-night stands became sexless friendships, and how other sexual partners became long-term lovers. The Farewell Symphony is also the author’s most frank and sexually explicit work of fiction. “If I had sex, say, with the average of three different partners a week from 1962 to 1982 in New York, then that means I fooled around with 3,120 men during my twenty years there,” his narrator, born in 1940, unabashedly reveals. “Nor did all this sex preclude intimacy,” he adds. “The best thing of all were the random, floating thoughts we shared.” As White’s narrator ages into the era of AIDS, it becomes harder to separate the factual author from his fictional alter ego. Like the author, the narrator of the novel figures as one of the early figures of the Gay Men’s Health Crisis, recalling such figures as Larry Kramer and Michel Foucault as friends, and tests HIV-positive. “I’d been most active in New York during what turned out to be the particularly dangerous years just before the disease began to manifest itself and was at last identified,” the narrator notes. “I’d always counted myself lucky,” he adds, upon finding out his HIV status, “until the day when I heard the long-denied but long-anticipated truth.” Also recommended: The Darker Proof, White early AIDS stories along with British author Adam Mars-Jones, The Burning Library, White’s collection of essays, and Skinned Alive, a collection of short stories.

Like People in History (1996) by Felice Picano.

Cousins Roger and Alistair become lifelong friends when they meet as boys in 1954. Picano was one of the first literary writers to understand the epic scope of the epidemic, how it was changing a generation of gay men. The novel opens in New York City in 1991, as Roger and his boyfriend are attending a birthday party for Alistair and flashes back as the two cousins live through major cultural moments of their generation, such as Woodstock, San Francisco in the Harvey Milk era, Fire Island summers, and AIDS activism in New York. Picano is best at recording the dishy dialogue of his characters and his natural ability to tell a story. Roger and Alistair are not so much campy gay characters, as they are an archetypical representation of what a fabulous gay life was supposed to be, which makes its conclusion particularly haunting. Also recommended: Picano’s True Stories and True Stories Too, which includes his nonfiction narratives, portraits, anecdotes and reminisces of many of his friends and colleagues lost to AIDS.

The Hours by Michael Cunningham (1998)

Much has been written about the importance of Michael Cunningham’s Pulitzer-prize winning novel The Hours. Clarissa Vaughan, a fifty-two year-old book editor in “unnaturally good health” who lives in Greenwich Village at “the end of the twentieth century,” is affectionately dubbed as “Mrs. Dalloway” by her best friend and former lover, Richard, an ailing gay poet with AIDS. In Michael Cunningham’s evocative novel, Clarissa, like the fictional character created by the author Virginia Woolf, shops for flowers, reflects on her life as she moves through the city streets, sees someone famous, meets an old acquaintance, and is planning a party. Richard, a “man with no T-cells at all” who is “disappearing into his illness,” is being honored that evening with a major literary prize. If it were not for Cunningham’s previous body of work, two richly prosaic novels, At Home at the End of the World and Flesh and Blood, one could worry that the effortless, stream of consciousness prose the author employs in The Hours was achieved by merely mimicking Woolf’s voice, plot, and point of view. But Cunningham has deftly created a trio of richly interwoven tales which alternate with one another chapter by chapter, each of which enters the thoughts of a character as she moves through the small details of a day. Throughout all of this, however, is the specter and muse of Woolf. Like the parallel story of Septimus Warren Smith and his private world of madness in Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway, Cunningham uses the details of each of his tales and characters to illuminate one another.

Where the Rainbow Ends (1998) by Jameson Currier

My first novel, Where The Rainbow Ends, took me more than four years to write. The novel, which spans more than fourteen years, follows a set of friends from 1978 to 1992, from the idyllic sexual revelry of Manhattan in the late 1970s to the transformation of the city into the epicenter of the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s, to the characters’ evolution into activists and parents in Los Angeles in the 1990s. I stopped and started the writing of this novel several times—to do other projects, to earn a living, and, to my amazement, to fall in love. But I always returned to this novel, embellishing or adding another scene, struggling onward with developing the theme: a young gay man’s search for faith and understanding during difficult times. I reached a point, however, somewhere within the last year I was writing this book, of not wanting to complete the novel. My characters had become, in many ways, as real to me as my own friends, and the intent of my plot was to propel these characters into the initiation, horrors and psychological confusion brought upon by AIDS, from their early shock and denial to their subsequent grief and anger. Several characters die within this book from the unexpected and untimely tragedy of this irrational virus. Writing these portions of the book required me not only to visualize the deaths of these characters but also regurgitate memories of the many friends I had already lost to this senseless illness. Who in their right mind would willingly invite disease and death into their life like this, over and over? This was only one of the problems I faced with writing my own novel about AIDS.

Hard (2006) by Wayne Hoffman

I was a fan of Wayne Hoffman’s long before he published his first novel Hard; in the late 1990s we worked together at The New York Blade News. I was always impressed by Wayne’s sharp observations of popular culture (at the time, he was the Arts Editor), but it was also obvious to me that he had a clear and passionate interest in the field of sexual politics (he was also one of the co-editors of the anthology Policing Public Sex). Wayne eventually became Managing Editor of The Blade, and throughout his impressive career as a journalist, he has contributed articles and reviews to a number of local and national publications. Hoffman moved to New York City in 1993, shortly after graduating from Tufts University. He set his extraordinary debut novel, Hard, in Manhattan in the late-1990s during the city’s “sex wars,” a time when a conservative mayor and the city government were cracking down on public sex venues under the auspices of preventing the spread of HIV. Hoffman’s details and descriptions of city-life and the gay community of this era are superbly drawn (and he does present a “gay community” in Hard—from buff-bod hustlers to hunky bears to HIV-positive ex-lovers), and he easily displays how this gay community overlaps with many other professional communities, such as those of journalism, advertising, travel, and, in particular, the theatrical community; many of his gay characters in Hard are also actors, playwrights, producers, and critics. While the political construct is what makes this novel so unique in gay fiction, it is Hoffman’s dead-on descriptions (witty and wise) of his characters’ sexual psyche that make it soar. (One character, in fact, runs a delightful cost-analysis on how much his search for sex costs him.) But I am also happy to report, that while Hard is political, sexy, comic, and full of social-consciousness, it is also encased in a surprising romantic yearning. Many critics and fellow-journalists have compared Hoffman’s Hard to Larry Kramer’s 1977 novel Faggots, another enormously brave, comic, and risky novel that peered into the sexual yearnings of gay men and the comparison of the two works is apt. Hard, however, factors in the impact of the anxieties and activism of the modern AIDS era that did not exist in the 1970s that Kramer was portraying. And while Hard is a complex weave of nuanced sexual and political situations and scenes, the primary conflict is between two gay journalists: one, Frank DeSoto, an AIDS widower and gay newspaper publisher approaching fifty who wants to see all the sex clubs and adult theaters shut down, and the other, Moe Pearlman, a twenty-six year-old sex-positive activist and would-be journalist who wants to keep them open. While trying to start up an alternative gay newspaper to provide what he feels is a more objective depiction of gay life in the New York, Moe also spends his spare time arranging safe-sex parties and giving the best blowjobs in the city. He views the closures of the adult theaters and sex clubs as a personal assault on his sex life.

__________

This article was originally published on Chelsea Station on May 26, 2014. Author sketches are by Jameson Currier, 2025.