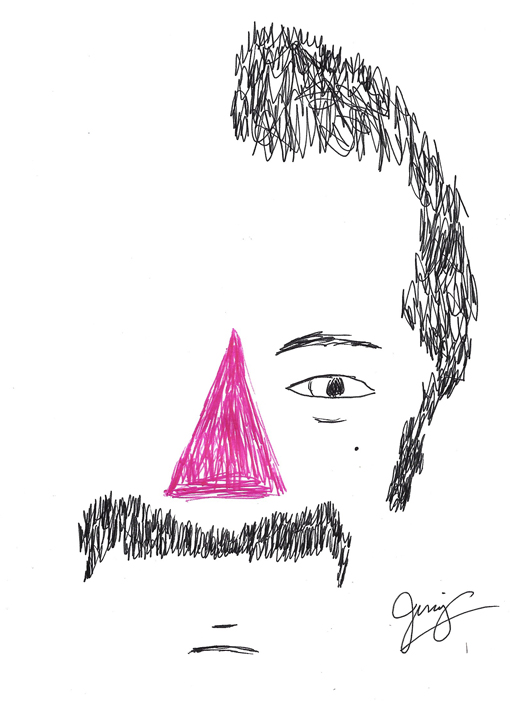

sketch of David B. Feinberg

by Jameson Currier

Ink on paper

20200506001

FUNNY GUY

by Jameson Currier

David B. Feinberg was a very funny guy. But I do not have a funny story about him. Our friendship was not based on his perpetual sense of humor or my often lack of one. Instead, it was founded on our mutual desire to be writers—gay writers grappling with and writing about the changes of life we had experience because of the epidemic of AIDS, gay men who, incidentally, knew what gay life was like before the epidemic.

I first met David in 1987 when I joined the Gay Writers Workshop, a group of about five or six writers who met once a month in members’ apartments throughout the metropolitan New York City area. David had been a member for some time, and though we had no leader to our group—we considered ourselves peers—we all looked to David to be our leader. Most of us had been minimally published, and David, by that time, had just begun writing his humor columns for Mandate magazine.

The writers in our group were a diverse lot. One guy was writing a gay version of Romeo and Juliet, another was concentrating on poetry, another was developing the saga of a drag queen who attended law school. It was clear right from the start, however, that David and I were writing about the same subject—gay life during the plague years—but our approach was wildly dissimilar—his fiction was dark, humorous, and witty, and focused around being HIV-positive, as he was in real life; my short stories were realistic, minimalistic, and compassionate, as I tried to understand my role as a carepartner for a friend who was struggling with many of the issues David, himself, would later deal with.

Not long after I joined the group, David had his first novel, Eighty-Sixed, accepted by Viking. Each month when our workshop met David would update the other members on the publishing process, flashing the proofs of the jacket cover of his book around the room or waving the author’s questionnaire he had received from the publicity department to fill out, adding little joking asides about the experience. He didn’t do this to brag, really, though many of us were ruffled a bit by it, each of us was continually sending our writings out and facing rejections. David believed, I think, that each one of us would one day go through this same process ourselves, which is why he was so eager to share his experience of it. A few months later, after I gave him a collection of my short stories that I had finished—half of which dealt with the impact of AIDS on the gay community—he surprised me and sent them along to his editor at Viking to consider—perhaps one of the most generous things one writer can do for another.

As it happened, that collection was not published, though it did serve as my introduction to Ed Iwanicki, the man who would become the editor of a later collection of my short stories that was published and who continued to edit David’s subsequent books. Real life, however, suspended a lot of my desire and momentum to be a writer—my friend died and I moved away from Manhattan and went through what I have often called my “minor major nervous meltdown” period. David, however, continued his “Life in Hell”—a highway of memorials, demonstrations, and doctors’ visits. And he continued writing about every aspect of it. Eventually I returned to the city, emotionally stronger, and moved into an apartment in the Theater District, a few blocks down from where David lived on Ninth Avenue, an area he had affectionately dubbed as “Hell’s Kitchenette.”

Occasionally I would run into David on the street and he would go into a riff about his anal warts or something equally as shocking. David was never squeamish about disclosure of anything, and I would often stand in front of him thinking that if I was shocked about hearing about anal warts on Ninth Avenue then what would my mother think about this? Or better yet, what would David’s mother think about it? After all, his family was often his fondest, quickest, and easiest source of comic anguish—as was mine, one of the many things I felt which connected us emotionally. A few minutes later, David would tell me he was having a party on such and such date and to be sure to come. And a few days later an invitation or a postcard would arrive in the mail reminding me of it. I have never been much of a party person, but I would go to David’s parties because I liked David, curious about how many people he could fit into the sliver of his apartment, curious, as well, as to what sort of crowd his other friends were. I had, by then, heard and read many, many stories about them.

David’s apartment, in those days, was painted a light shade of lavender, with a darker colored trim, and on the wall by his bed was an enormous collage of photographs and drawings of men that David admired—the “hot ones” as they were called—culled from a variety of publications such as Advocate Men, Torso, the International Male catalog or the advertisements for the Chelsea Gym that would often appear in The Village Voice. It was as easy to be drawn to this wall of beautiful faces and bodies as it was to David and his real world, but I could never stay long at his parties, shyness and a need for fresh air would pull me back out onto the street. As I would walk back to my apartment, I would often dwell on the differences between David and myself—the photographs I had clipped of men that interested me, for instance, my hot ones, were hidden in a drawer beside my bed, never to be displayed in public, never, even, shared privately with another man.

It was in the fall of 1993, I think, that I noticed that things were really beginning to change for David. I ran into him at the bus stop—he was headed downtown to his new apartment in Chelsea, the one that a boyfriend had hand-painted a wall trim near the ceiling that David despised—and I could tell he had dropped weight. Not long after that I decided that I would start going to ACT UP meetings on Monday nights because I felt I needed to find a more angrier and political approach to my writing. What I found, instead, was a way to find David.

And so it happened that on Monday nights I would wander into ACT UP and look for David, say hello, briefly gossip, and sometimes sit beside him, listening to him mumble asides as he scribbled notes on the photocopied agenda, his free arm draped around my shoulder or touching my thigh to make a point. I don’t think I really ever officially joined ACT UP; I had wandered in and out of meetings for years and shown up for a few of the bigger actions and rallies, and when I started going again I never felt as if I were rejoining the group. Instead, I felt I was joining David.

ACT UP, Monday nights at The Lesbian and Gay Center in the West Village, was somewhere where I knew I could find David, even if it just meant spotting him across the room. This was the place where I could check up on him without really seeming to check up on him. I suppose this voyeuristic distance is just another part of my WASPy upbringing, that polite reserve of wanting to know but not wanting to ask, the Southern writer whose view of the canvas is of a broad perspective as opposed to the Northern activist whose life is specific and lived on the edge and at the front lines. David, of course, went on to denounce ACT UP in the last month of his life; in an infamous speech delivered to the organization on the night he was released from the hospital for the last time, he chided them for wasting time bickering amongst themselves and “indulging in its obsession with the Catholic church.”

In addition to being a funny guy, David was also a consummate critic. One of his favorite pastimes was to pick up the phone and play “trash the reading” or “trash the movie” or “trash the play”—a game, I will also admit, he was much more superb at than I. I often feared, even, that one day I might fall victim to his satirical attacks. One night, for instance, at a benefit screening for a documentary I wrote called Living Proof, based on the Carolyn Jones photography project about people who are successfully living with their HIV diagnosis and in which David had a five-second appearance, David waved me over through the crowd at the theater and asked me to sit beside him. When the lights came up at the end of the movie, I tried to push my way into the aisle, fearful of being caught in a “trash the movie” scenario in which I did not want to participate. But I couldn’t get away, caught in the crowd, and I stood with my back toward David, not wanting, at that moment, to know his opinion. The movie, after all, was upbeat and positive about living with HIV, and David, I knew from our conversation earlier that evening, was struggling with issues of his own dying and death. In the lobby, before the movie had started, he had confided to me that he was worried about living to see his next book—Queer and Loathing—published, and I knew he wasn’t exactly feeling in a positive or upbeat mood about anything that evening. He must have sensed my worry, however, sensed my sensitivity, because he clasped my shoulder and said, “It even made me feel good,” and then, in that dry, nasal tone of his, as if to deflect his own good mood, added, “For a moment.”

I once defended David to a reporter by saying that sometimes it takes a sense of humor to understand a sense of humor. At his darkest, David could also be potentially offensive—he seldom held anything back when it was on his mind. Personally, I often felt so inadequate around him—I have never considered myself a funny guy; at best, my sense of humor is either situational or very dry. I was not always tuned into David’s satirical wavelength, but I could always rationalize the genesis of his humor. David was always on, as if he were isolated in a soundbooth and being broadcast across something like AIDS Public Radio. Sometimes, however, when he would go into one of his riffs, I would stop him with a “What? What?”—not totally comprehending what he was saying (or hearing—David was also a superb mumbler). Oftentimes, I would question him purposely, or bequeath him one of my unknowing blank stares, my own sort of private joke with him: Nothing is more funny to me than making a comic have to explain his own joke, one that David enjoyed having to do in my company. And I enjoyed playing his straight man.

David’s humor, both in person and in print, was frank and ferocious. Critics often cited him for his lack of self-pity. He was one of the first, if not the first, to write humorously about AIDS, paving the way, in essence, for other writers to write comically about life in the epidemic, particularly the string of comic plays about AIDS that appeared in the early Nineties by Paul Rudnick, Christopher Durang, Terrence McNally, and Tony Kushner. Though David once said to a reporter that B.J. Rosenthal, his randy and troubled fictional alter-ego in Eighty-Sixed and Spontaneous Combustion, was “more well-endowed” than himself, he was nonetheless quite close to the same skin as David. One of the hardest things for a writer who writes creatively about AIDS is to be able to separate the fiction from the facts of his experiences, and which is why David’s last book, Queer and Loathing, a collection of his non-fiction articles about living with HIV, is perhaps his most insightful, intimate, and controversial book because David did not steer away from any of his own truths, adventures, and opinions. David was also an extraordinary journalist, often using a first-person narrative technique that would not only describe an event, but one which could capture an absurdly comic portrait of himself within it.

Is humor an acceptable way for an activist to write about AIDS? Certainly, it is one of the most viable and accessible ways to stress and reveal the troubling truths of the epidemic, at least in my opinion, but it was also a point which polarized David against many other gay men, gay writers, gay editors, and gay publications. Edmund White, himself HIV-positive and co-author of a collection of AIDS fiction titled The Darker Proof, wrote in an essay entitled “Esthetics and Loss” in Artforum in 1987, “If art is to confront AIDS more honestly than the media has done, it must begin in tact, avoid humor and end in anger.”

Avoid humor? The thought of it could send David into spasms of laughter. David, incensed by White’s logic, went on to campaign for more humor in AIDS writing, expressing himself eloquently on the subject in The Advocate and at the 1992 OutWrite conference of gay and lesbian writers and editors in Boston, as well as on numerous panels. “I’m not trivializing AIDS,” he told an interviewer in 1992. “I’ve seen too many people die. It’s hard to write about AIDS. If I wrote about it straight, I couldn’t face it. In a lot of ways, this is therapy for me. I had a lot of anger and depression in me when I learned I was HIV-positive. Some of the anger I channeled into ACT UP, the rest I sublimated into writing. Part of why I do it in a humorous way is to make it manageable for me. Humor is a way of taking control—or trying to. If you laugh at a situation, it’s no longer in control of you. You’re in charge. For a minute, anyway.”

One of the ironies of this anecdote was supplied by Edmund White, himself. In Muses from Chaos and Ash: AIDS, Artists, and Art, published in 1993, White remarked, “I’d really like to write a big novel, probably similar in form to David Feinberg’s Eighty-Sixed. That’s probably been the most successful of all the AIDS novels.” This was the same author who had earlier suggested that it was inappropriate to combine AIDS and humor and who went on further in this interview to compliment David’s book as “quite funny” and “full of all the characteristic verve and excitement of gay life of that period.”

Even at the end David continued to be funny; and he continued to write. In the hospital the last two months of his life he filled a composition book with sketches, lists, and anecdotes of his often trying and humiliating medical experiences. If there was any particular technique that David originated or perfected in his writing, I would have to say it was his lists, which he incorporated into both Eighty-Sixed and Spontaneous Combustion, but which became the barometers of David’s emotional and physical health in Queer and Loathing. As David’s health deteriorated, his humor, of course, became darker and darker.

I have, of course, many other personal memories of David—the way he gathered his friends together to see a movie on Christmas Eve, listening to his riffs about Bob Satuloff or the Native erroneously reporting the demise of his best friend John Weir, Ryan White’s remark about how he was an “innocent victim” and David’s succinct reply, “Right, the rest of us deserve to die,” the photos he would take of the audience at his bookstore readings, watching him barely breathing as he watched his stage play being read before an audience of friends, the provocative postcards he would send me of bare-bottomed gym boys.

These are, of course, only my memories of David; others, I am sure, have much more riotous and vivid recollections of him. I was not part of his inner circle and he was not a part of mine, but our orbits crossed nonetheless in this expansive and crazy metropolis because of the epidemic. And, oddly, I have to say, the epidemic created a stronger friendship between us. Each of us could have taken the other to task for the way we wrote about the disease, but there was something between us, a desire to see an end to this plague and a realistic need to report its continuing uncertainties that kept our respect in check with one another.

So I will write it again because I really mean it. David B. Feinberg was a very funny guy. He was also a great and original writer. His sense of humor prevailed even as it was tested by the ravages of a virus that invaded, disrupted, and humiliated his body. Unfortunately, I must also remember him as another friend lost in the epidemic. David died November 2, 1994 at the age of thirty-seven.

__________

“Funny Guy” was first published in 1994 in Body Positive and was reprinted in Until My Heart Stops, Intimate Writings by Jameson Currier (Chelsea Station, 2015).