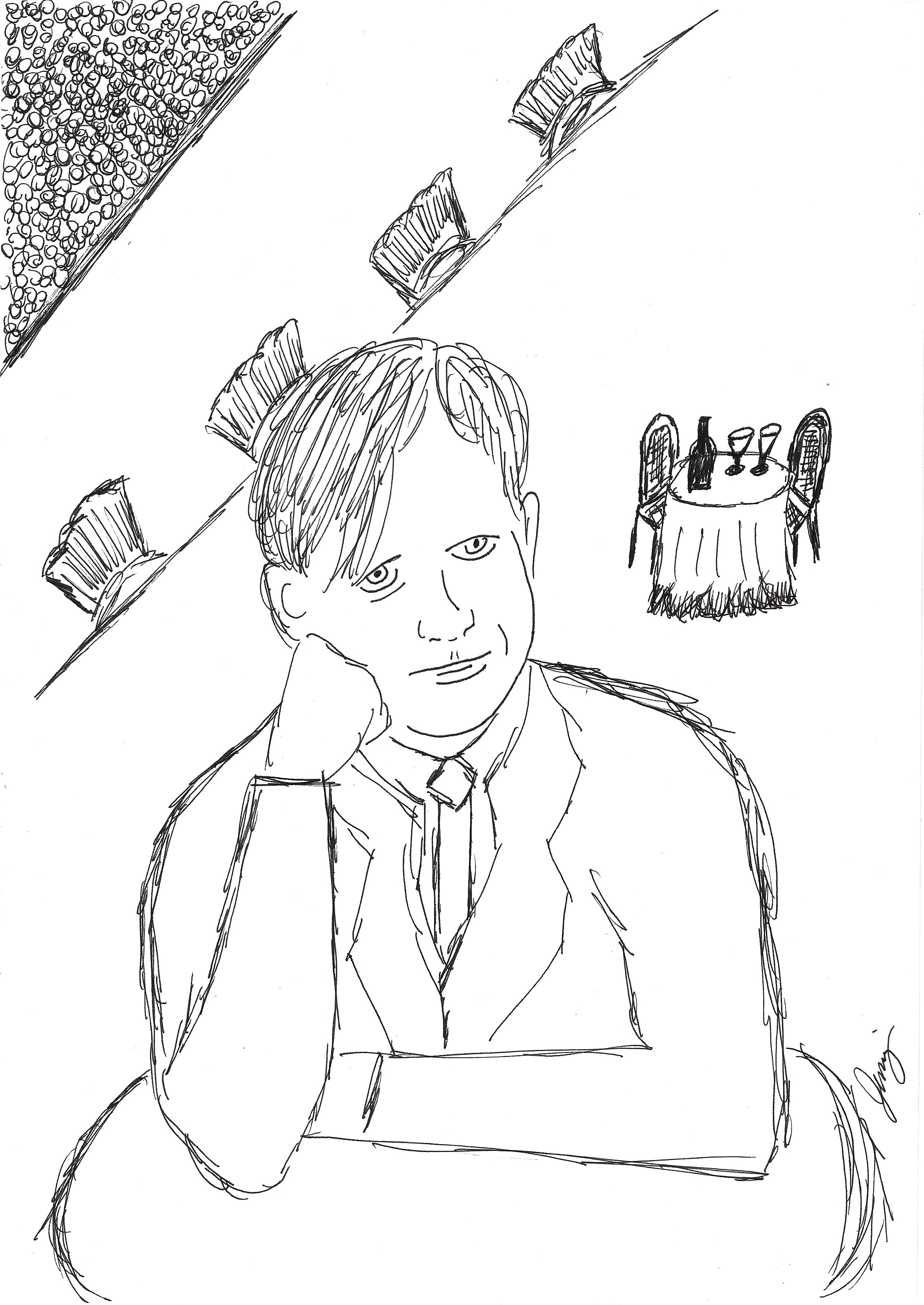

“At the Cabaret”

sketch of Christopher Isherwood

art by Jameson Currier

Ink on 9 x 12 inch sketch paper

20200531002

On Isherwood

Review by Jameson Currier

Christopher Isherwood was a member of a talented group of young, left-wing British writers of the 1930s that included W. H. Auden, C. Day Lewis, and Stephen Spender. Living in Germany during Hitler’s rise to power, Isherwood detailed the social corruption of Weimar Berlin in his witty and observant novels Mr. Norris Changes Trains and Goodbye to Berlin. Goodbye to Berlin, in turn, would later be adapted (by John van Druten) into the Broadway play, I Am a Camera, which in turn would later serve as the inspiration for the Broadway and film musical Cabaret.

Isherwood wrote in his diary several times a week from the 1920s to 1985, a year before his death, recording and clarifying his thoughts, disciplining himself during periods of laziness or dissipation, setting down gossip, jokes, or the details of his latest quarrel or disruption — all as a need to account for himself.

Though many of the author’s pre-1939 diaries have not survived, Christopher Isherwood, Diaries, Volume One: 1939-1960 begins on January 19, 1939, the day Isherwood, at the age of thirty-four, left England for America with W. H. Auden, bound for Manhattan.

As these diaries beautifully illustrate, Isherwood did not remain in New York for long. Unable to work and obsessed about the possibility of a coming war and his stance as a pacifist, Isherwood set out for California a few months later hoping to find guidance and advice from his friends Gerald Heard and Aldous Huxley in Los Angeles, a city Isherwood noted was “perhaps the ugliest city on earth” but where he would nevertheless settle and consider home.

During that eventful summer of 1939 in California, Heard introduced Isherwood to Swami Prabhavananda, the resident monk of the Ramakrishna Mission in Hollywood, and Isherwood soon embarked on a spiritual journey, as the Swami began to instruct the writer in meditation and Hindu ritual and belief. The guru-disciple relationship was attractive to Isherwood’s intellectual and psychological make-up, in part because the Swami did not regard Isherwood’s homosexuality as a sin.

Much of Isherwood’s subsequent writing was devoted to popularizing aspects of Hinduism, translating the Bhagavad Gita and other Hindu scriptures. Isherwood’s diaries reveal his early (and often unsuccessful) attempts at meditation, how his sexuality often undermined his frequent resolve to remain celibate, as well as the human imperfections of a spiritual leader.

“I’ve even felt much more at ease with the Swami since I noticed his flashy shoes,” Isherwood dryly observes.

This volume of Isherwood diaries spans more than twenty years in the author’s life and includes the evolution of his relationship with artist Don Bachardy, whom Isherwood met as a young man of eighteen and who became Isherwood’s companion for more than thirty years.

It should be noted, however, that the beginning portion of this volume of Isherwood Diaries (a second volume beginning with the latter half of 1960 and continuing through 1985 is forthcoming) is based upon a series of diaries which the writer kept irregularly during the years 1939 to 1944 and which Isherwood revised and expanded in 1946. This rewriting produces a clear narrative prose which reads more like an autobiography than an honest diary.

Nonetheless, this volume still contains much of what could be considered mundane in any diary; there are several accounts of dishwashing, innumerable attempts to stop smoking, a visit from an exterminator, and abundant infighting within the author’s circle of friendships and his adopted religion.

But for the most part these diaries are chock full of fascinating details and stories. Isherwood, after all, lived a name-dropping life. While in Los Angeles the author worked on several film projects, many quick and high paying, including a stint at MGM. There are fabulous anecdotes included in this volume about Garbo, Chaplin, Milton Berle, Frank Lloyd Wright, Charles Laughton, and young Gore Vidal. Literati delightfully pop in and out of Isherwood’s life; also included is an exquisite tribute to the writer Dylan Thomas.

Isherwood’s prose in these diary entries are also full of rich and splendid character details: of Garbo, for instance, he writes: “If you watch her for a quarter of an hour, you see every one of her famous expressions.”

Editor Katherine Bucknell has also done a remarkable job in compiling a chronology of the author’s life and including a detailed introduction and an encyclopedic glossary of Isherwood’s world.

Isherwood drew on the diary entries of this period for his later novels The World in the Evening, Down There on a Visit, A Single Man and his autobiographical book My Guru and His Disciple, and this volume serves best as an important adjunct to these works as well as an engaging historical record of a complex personality and era.

_______________

CHRISTOPHER ISHERWOOD, DIARIES, VOLUME ONE, 1939-1960

Edited and Introduced by Katherine Bucknell (HarperCollins)

This review of Christopher Isherwood Diaries Volume One 1939-1960 was published as “Journals Gained in Retrospect,” in the Dallas Morning News, March 9, 1997.