Sketch of Armistead Maupin

by Jameson Currier

ink on paper

20250124001

Review by Jameson Currier

First things first. It’s hard to be objective about a book that makes you effortlessly smile… and weep, and Armistead Maupin’s new novel, Michael Tolliver Lives, does both. In fact, I confess that I could not put this book down until I finished it, tugged by the glow and melodrama of memories — both Maupin’s and my own.

Let me explain.

Back in the dark ages of the 1970s, before cellphones and iPods and YouTube, before Will and Grace and Sex in the City, Armistead Maupin created a newspaper serial about the charming and quirky residents of 28 Barbary Lane in San Francisco. The serials became a series of books — Tales of the City, More Tales of the City, and Further Tales of the City — with three more sequels arriving like bestselling clockwork — Baby Cakes, Significant Others, and Sure of You. I adored each one. The books were lent to friends and passed along to other friends, who lent them to other friends. There were phone calls and discussions at bars and dinner parties on which book we liked best and what character was our favorite. Years later, when PBS (and later Showtime) announced they were broadcasting mini-series based on the books (and funded by a British network), it was met first by disbelief, and then by awe at their ability to recapture the exhilaration of reading the novels for the first time.

I read the first two Tales in 1980 back to back. They were gifts from a friend, now long gone, who knew I wanted to be a writer. It’s hard for me to imagine how my life would have been without these books. In an era when there were few positive role models for the queer community, Armistead Maupin showed many of us what a fabulous gay life we could expect to find in a big city with a family of friends.

The sixth Tales book, Sure of You, ended in 1989, with Michael “Mouse” Tolliver HIV-positive, and in 1989 many of us believed that this was not a good sign. San Francisco was a bleak world none of us could have imagined it would become, ravaged and disrupted by the AIDS epidemic. Michael Tolliver Lives begins almost two decades later with Michael, now approaching 55, buoyed by a drug cocktail and “glad to belong to this sweet confederacy of survivors.”

Transsexual landlady Anna Madrigal, the heart and soul of 28 Barbary Lane, is also a survivor. At 85, she has been slowed by a stroke, but is as radiant as ever, now living in the Dubose Triangle in a garden apartment on level terrain surrounded by another quirky assortment of neighbors, among them a handsome transman named Jake Greenleaf who works as a gardener with Michael. Michael now lives with his lover Ben, a 33-year-old furniture designer, 21 years younger than he is — “an entire adult younger, if you must insist on looking at it that way.”

The plot of Michael Tolliver Lives, for the most part, revolves around the fragility of Mrs. Madrigal and the fragility of Michael’s mother, “confined to a Christian-run convalescent home in Orlovista, Florida for the past six years.” Michael is tugged between his biological family and his “logical” one. Along the way we spend some time in Florida with Michael’s brother Irwin, a Christian realtor, Irwin’s wife Lenore, who expresses her faith through puppets, and their flamboyant seven year-old grandson Sumter. We also revisit many of Michael’s friends from the earlier Tales — both the survivors and the departed. Brian Hawkins, another former resident of Barbary Lane, is now 61, “twenty (or so) pounds heavier,” and looking towards retirement in an RV. His daughter, Shawna, is a sex columnist who wants to move to New York. Mary Ann Singleton is well-to-do Mary Ann Caruthers of Darien, Connecticut. Jon, Connie, D’orothea, DeDe, Mona, and Mother Mucca are also fondly remembered. The new characters introduced in this novel are just as delicious as their predecessors, among them Michael’s mother’s hairdresser, Patreese, who moonlights as a male stripper. And even though she’s somewhat older, Mrs. Madrigal continues to work her magic and mischief, as integral to this story as the others.

Written in the first person — from Michael’s point of view — Michael Tolliver Lives at times feels more like a memoir than a novel to me, perhaps because I harbor the belief that Mouse is an old friend I haven’t heard from in a while (and delighted to find is still around). It is this personal perspective that gives the novel its richness, power, sentiment, and distinction. Maupin’s talent as a social historian, glancing both backwards and forwards, is exhilarating. Michael drives a hybrid Prius, injects testosterone, pops Viagra, and tells his lover, “You take me back to my best times. I feel connected to them again.” Michael, in fact, is a historical bridge between the older generation and the younger one, recalling life as it was to life as it is today.

And thankfully, Michael does not shy away from reveling in his sex life— past or present. Michael might not remember a guy’s name he hasn’t seen in nineteen years, but he does remember his dick, “how the less-than-average length was made irrelevant by its girth. It was one of the thickest I’d ever seen, with a head that flared like a caveman’s club”

Married at City Hall, Michael and Ben maintain an open relationship, “a tricky little dance sometimes, but it’s preferable to the perils of endless monogamy or constant whoring.” Michael weighs in on cybersex, macho manginas, and pregnant sex-workers, and occasionally sends his lover off to the local bathhouse. I won’t spoil all the fun Maupin has in store except to say that Michael also embarks on an amusing and arousing three-way.

Maupin insists that Michael Tolliver Lives is not a sequel and not the seventh book in the Tales of the City series. I’m certain that this novel could stand on its own merits, if a reader had not visited the earlier tales. But who would want to avoid the pleasure and heartbreak, the undeniably sweet tug of nostalgia and the tsunami of emotions that experiencing the series, along with Michael Tolliver Lives, delivers?

Like I said earlier, it’s hard to be objective about something that has had such a profound impact on who you are. My advice would be to read all seven books. And pass them along to your friends.

Michael Tolliver Lives

by Armistead Maupin

(Harpercollins, 2007)

__________________

This review was originally published in Lambda Book Report, Fall 2007, p. 5.

__________________

Reviewer’s Note (2025):

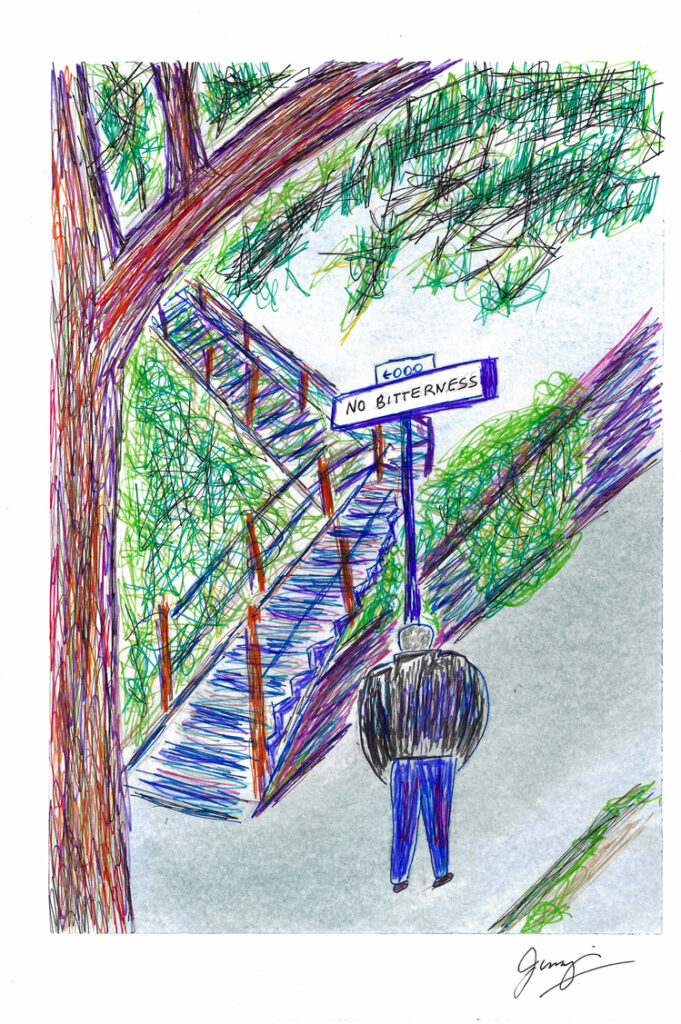

A significant influence on my desire to be a writer were the novels of Armistead Maupin. Tales of the City was a revelation. I read it when it was first released. It captured the exuberance of being gay and having a chosen family of gay and straight friends in a big city in a way that the elusive and exclusive Fire Island fiction of the Violet Quill did not. One of the disappointments of my journalism career, however, was being turned down by an officious publicist when I asked to interview Maupin during the release of Michael Tolliver Lives. I didn’t let it cloud my review of the novel, and, in retrospect, I realize that if the interview had taken place that I would have been too polite and fawning, something that I dislike displaying because I feel I may come across as disingenuous and phony. But the publicist’s dismission did cloud my desire to continue to write about the author and read his subsequent works.

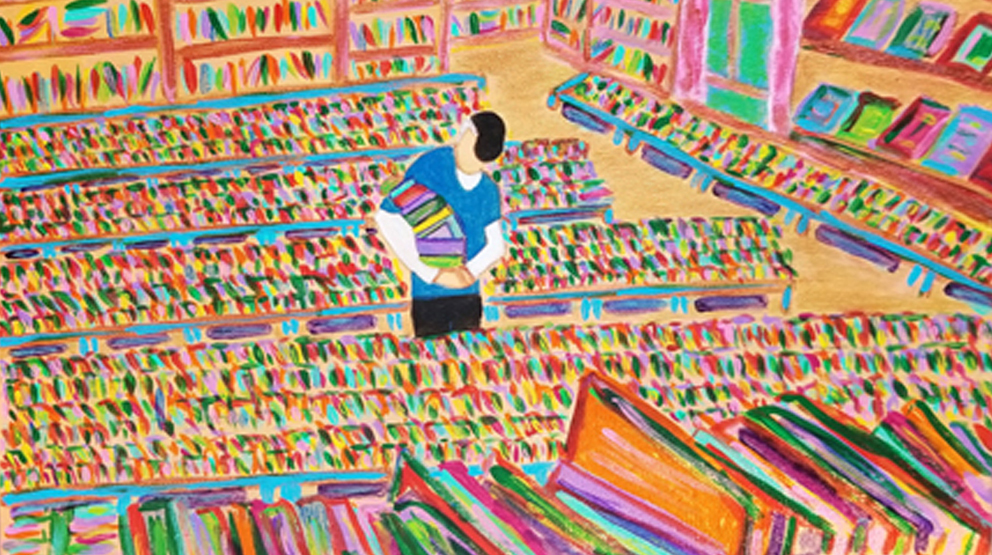

“No Bitterness: A Portrait of a Tale”

art by Jameson Currier

Ink and pastel on paper

20200506002