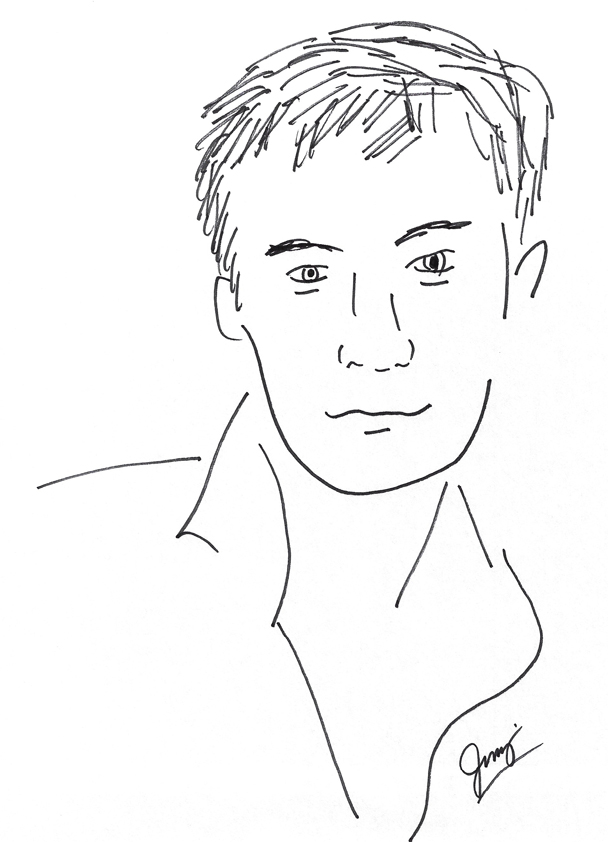

Sketch of John Rechy

by Jameson Currier

ink on paper

20250124002

Interview by Jameson Currier

When author John Rechy first heard that he would receive the William Whitehead Award, he thought perhaps someone was playing a malicious prank on him.

‘‘No one called again for a couple of days,” Rechy says, ‘“and I told my partner that it might not be true.”

But it was true. And now that Rechy is preparing for his trip to New York next week to receive the literary prize from the Publishing Triangle, an association of lesbians and gay men in publishing, Rechy has realized how much the recognition means to him. Although he has won other awards and landed books on mainstream bestseller lists, Rechy has never won a gay literary prize before. The Whitehead Award puts him in the ranks of the gay community’s literary giants; past winners have included Armistead Maupin, Audre Lorde, and Edmund White.

“You never feel like you’re a legendary figure when you wake up and you’re disgruntled and you need a cup of coffee,” he says. “But it’s a great honor to be recognized by your industry and peers. And this is the first time I’ve been acknowledged and honored by the gay community in any way.”

Rechy is hardly unknown in the gay community, though; perhaps more than any other American author in the 20th century, his writings have helped shape the sexual consciousness of several generations of gay men. Over the course of four decades, he has written 12 books—one non-fiction “documentary’’ and 11 novels, the latest of which will be published this summer.

His reputation took off with his first novel City of Night, a largely autobiographical work published in 1963, which documents the wanderings of a nameless male hustler from El Paso to New York: City. City of Night landed in bookstores and libraries across the country at a time when young gay men battling with accepting their sexual identities had few places to tum. For many, Rechy’s book was their first taste of gay culture.

Richard Labonte, a critic, editor, and the general manager of San Francisco’s A Different Light Bookstore, says he read City of Night at the age of 13 and now considers it one of the 10 best gay books ever written.

‘‘I always recommend City of Night because it was the first overtly gay and sexual book I read myself,” says Labonte. ‘‘It’s a remarkable fusion of brilliant writing and reporting and unapologetic sexual energy. It’s a book about the sexual underworld, sure, but it’s written with such power and such grace that any reader knows there’s a world beyond its pages.”

While other authors published gay-themed works prior to City of Night—among them James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room and Gore Vidal’s The City and the Pillar—none had the gay male sexual experience as its focal element. And no other writer before Rechy had allowed the reader to vicariously experience the sexual mindset of a contemporary gay man.

Critic and author Michael Bronski, who will introduce Rechy when he is presented with his award on April 8, notes that City of Night ‘‘literally changed how gay male life as a culture was presented in the mainstream American media.”

“City of Night was like a stunning anthropological report—sociology from the inside,” Bronski says. ‘‘It foregrounded the importance and vitality, the incredible customs and structure of this culture in a way that previous books did not. Granted, it was only one aspect of the gay male experience—the grungy, sometimes lonely nightlife of Times Square, hustling and hunting for sex—but the book was about gay men and gay male culture.”

City of Night began as a letter Rechy wrote to a friend about his experiences at Mardi Gras and was then reworked as a short story for the literary magazine Evergreen Review.

Rechy, then in his 20s, continued writing and publishing portions of the book as he moved across the country, hustling to earn a living. Rechy spent four years writing the book.

With such noted figures as Baldwin and Norman Mailer championing his writing, several publishing houses made offers on the novel even before it was completed. Once it was released, City of Night landed in the number seven spot of Publisher’s Weekly’s national bestseller list for 1963.

‘‘The popularity of City of Night ensured that blatantly gay sexual material could be bought over the counter,” Bronski says. ‘‘Rechy’s literary reputation made it possible to buy the book—and later Numbers—and pretend that you might be interested in literature.

‘‘Here were gay men who were having sex, and to a large degree enjoying it,” Bronski says. ‘‘And even when they were not really enjoying it very much, it was clear that sex was part of their lives, of their self-identity, of their emotional and psychological make-up. I was far more frightened by the idea that I was expected to grow up and be heterosexual and have kids and live in the suburbs than I was by the idea that I was doomed to live in New York or Los Angeles and be part of the gay scene.”

Though Rechy has often battled being labeled a “gay writer,” he points out that he always included gay characters in his novels. Charles Flowers, co-chair of the Publishing Triangle, says that by recognizing Rechy with the Whitehead Award, the organization hopes to “give him the long overdue recognition and celebration his work deserves, especially to younger generations of readers.”

But Labonte of A Different Light notes that in his 20 years of bookselling experience he’s noticed that there are certain writers who continually capture the attention of young, earnest, book-reading gay men—among them Jean Genet, William Burroughs, and Rechy.

“These aren’t authors I have to recommend,” Labonte says. “Customers find their work on the shelves and bring them to the counter on their own. There’s a genetic disposition at work.”

Rechy, a Mexican-American born in El Paso, Texas, studied journalism at Texas Western College and the New School for Social Research in New York before serving in Germany in the U.S. Army. After he was discharged, Rechy arrived in New York City and began the period of hustling and drifting that inspired his early fiction.

Rechy’s focus on specific elements of gay culture—such as narcissism, bodybuilding, and hustling—have often brought him unwelcome criticism in ways that many other authors writing on sexual subjects have not received. In fact, the author acknowledges that the critique of his sexual content has often overshadowed the more finely crafted elements of his works.

Indeed, Rechy’s writings are carefully conceived and executed, with as much emphasis on symbolism and structure as on developing characters and delineating settings specific to gay culture. Rechy notes that the poet and author Terry Southern once called him an “accidental writer.”

“There is nothing accidental about my writing,” Rechy says. “I have always been a very literary writer.”

Rechy’s novel Rushes, for example, about the patrons in a leather bar, uses the structure of a Catholic Mass for its chapters. In Numbers, Johnny Rio, the former hustler who now pursues only free sex, becomes a more sharply defined character through his sexual encounters, while the men he meets turn into a nameless and faceless blur. And in The Sexual Outlaw, his only non-fiction work, Rechy intersperses essays on subjects from pride parades to S&M between a fractured narrative of a gay man moving through three days and nights in Los Angeles’ sexual underground.

“I’m the best critic of my work,” Rechy says. ‘‘And I’m very critical of my own work.” But Rechy has found one criticism particularly stinging throughout his career. Critic Alfred Chester, reviewing City of Night for The New York Review of Books called the novel ‘‘fabricated.” He wrote that, “despite the adorable photograph on the rear of the dust jacket, I can hardly believe there is a real John Rechy—and if there is, he would probably be the first to agree that there isn’t—for City of Night reads like the unTrue Confessions of a Male Whore as told to Jean Genet, Djuna Barnes, Truman Capote, Gore Vidal, Thomas Wolfe, Fanny Hurst, and Dr. Franzblau. It is pastiche from the word go.”

Since then, Rechy has waged an ongoing feud with Barbara Epstein, the Review’s editor, which was finally resolved some 30 years later in 1997, when Rechy was awarded the PEN USA Lifetime Achievement award and was allowed to write a rebuttal of the review in the publication.

Rechy is also a noted teacher; he has taught both literature and writing courses at the University of Southern California. In addition, Rechy conducts a private writing workshop, and he proudly acknowledges the achievements of his students. Among the writers he has taught have included noted gay author Michael Cunningham.

But Rechy himself is also being taught in literature courses in campuses around the country, including Harvard and Yale. A random sampling on the Internet reveals Rechy discussions currently being held at Wellesley, Colby, and San Antonio colleges. Recently, at Edinboro College, the author was designated as the subject of a single course: ‘‘The World of John Rechy.” And this summer The Annenberg Center at University of Southern California is releasing Memories and Desire: The Worlds of John Rechy, an interactive disc that will include photographs, maps, and descriptions of the author’s former cruising spots as well as samples of his writings.

Rechy’ s newest novel, The Coming of the Night, forthcoming summer 1999 from Grove Press, is a return to the themes of City of Night. Set during one day in 1981, the new novel incorporates the dawning of an AIDS awareness in his characters, a subject that he has addressed in articles and essays before but never in his fiction.

“It’s based on something I saw in 1981—a very beautiful 21-year-old kid in the park at 3 a.m. in the morning,” the author says. ‘‘He took of all his clothes and pasted his body against the tool shed and people proceeded to line up and fuck him. It was almost like a crucifixion and that had haunted me. After witnessing that I ran into a friend who I asked if it was true what I had heard of about a new gay illness.”

Rechy, who believes there is no such thing as writer’s block, is also at work on another novel titled The Naked Cowboy, based on handsome fellow he knew from Venice Beach. Rechy notes that his days are now structured around two of his ongoing passions: writing and bodybuilding.

“Writing is like working out with weights to me,” he says. “If l lose one day I’m disturbed and everything is wobbly.”

And Rechy is as focused on his workout regimen as he is with his writing. Now in his 60s, Rechy works out three days a week in 2 1/2-hour sessions at his home in Los Angeles.

“I look terrific and people assume that my photographs were taken of me years ago,” he says. “I’ m a longtime student and admirer of narcissism.”

Rechy admits that though he feels he has ‘‘matured” now, he still stands firm behind the elements and themes of his early writings, but notes that he could never write City of Night now.

“I find it’s a very romantic book,” he says.

But Rechy is hardly a man without sentiment. Rechy, the noted independent “sexual outlaw” also acknowledges that he has been in a relationship for more than 20 years with a man who is 25 years his junior.

“Don’t think I didn’t battle with the idea of it,” Rechy says. ‘‘I was never looking for it and this remarkable person came into my life and we have been entwined since.” Rechy says the two men share a house in Venice Beach during the summer and travel extensively together throughout the year.

Rechy’s visit to New York next week will be his first trip to the city in 13 years. But Rechy won’t be returning to his old stomping grounds, the newly renovated Times Square.

“I don’t think I’m even going to go down there,” he says. ‘‘I know I wouldn’t recognize it. It’s just like Pershing Square—the place I wrote about is entirely gone.”

____________

This interview with John Rechy was published as “Sexual Outlaw” in the New York Blade News (April 2, 1999) and as “The Coming of John Rechy,” Bay Area Reporter (August 5, 1999).