illustration by Jameson Currier

RIBBONS

by Jameson Currier

For years Janet had trained to be an actress, taken classes in movement and speech, paid vocal coaches to help her with audition material, had photographs and resumes printed and reprinted. She had toured the country in a nonunion production of a revue of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s music, then gotten her Equity card with an off-Broadway play that had subsequently closed in one night. Now, near forty, she was just growing into the types of character roles she had waited years to be able to perform. Her best friends were in the theater, wanted to be actors and designers and composers and writers; she met them in all parts of Manhattan for dinner and rehearsals, gossiped with them about new plays and musicals and backstage affairs. One evening, Janet went to a theater in the East Village to see her friend Allen perform Bertram in All’s Well That Ends Well, and, afterwards, in the lobby of the theater, a young man presented small loops of red ribbons to theater patrons to wear pinned on their clothing to promote an awareness of AIDS.

Janet took a ribbon, her first, and pinned it proudly to her jacket. She had lost friends since the early days of the epidemic, had sung at more memorial services than she liked to remember, had volunteered at booths and benefits for Broadway Cares and Equity Fights AIDS. Now she was relieved that there was finally a way to show her support, silently, without having to constantly say, I’m sorry. Friends were always confiding in her about someone who was sick or leaving a show; now, at last, there was a way to express her compassion.

The next day, Janet auditioned for a role in a touring production of The Sound of Music, and, as she was singing the final phrase of “Climb Every Mountain,” her tooth, a capped one, flew out of her mouth. Embarrassed, Janet lisped her apologies to the musical director and retreated to the lobby where she commiserated with her friends. Billy, a friend Janet had met from a production of A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, told Janet that a mutual friend of theirs, Reb, had died the day before. Stunned, Janet did not know how to respond, and she took another ribbon from a young man who was distributing them outside the rehearsal studio.

That day, Janet and Billy decided to go for lunch at a diner in Times Square, a place where they always went after auditions. There, Janet described to Billy an audition she had had the previous week where she forgot part of her monologue from The Glass Menagerie and began to ramble into a speech from Annie Hall. After their meals, Janet accidentally spilled a cup of coffee and stained her new blouse. Upset, Janet became annoyed when the waitress, a new one, could not bring her more napkins quick enough to wipe up the mess. When the waitress reappeared Janet asked where Sam, the regular waiter, was. Flustered, the waitress said she had heard he had been ill for a few weeks. At the cash register Janet took another red ribbon from a box on the counter and placed it inside her purse.

Sometimes Janet hated wearing her ribbon; to her it was neither a fashion statement nor a political act, but something she just had to do. Sometimes it made her feel shallow and insensitive; she always noticed the color was wrong and it threw off her hair, it clashed with every outfit she owned, but she continued to wear it to demonstrate her feelings, human feelings, feelings that she, too, was worried—worried not only for herself (she knew she was not immune to this virus) but also worried for her friends—friends who were defined as living in a high risk category.

Janet began noticing more and more ribbons, ribbons worn at auditions, at the theater, in bookstores and at the movies, on the subways and buses: satin, grosgrain, pavé, and rubied ones; even ribbons silkscreened onto clothing. At first Janet would study the faces of the other wearers, looking for some sort of sign as to how she should act: serious, solemn or proud, but then she reached a point where she never noticed faces, just ribbons in the distance: approaching, turning, following, retreating.

Days would pass between Janet’s auditions; her luck at the temporary typing or receptionist jobs she found to help pay her bills was not much better than what she found as an actress. She had answered phones in abandoned buildings, flooded offices, and at lopsided desks; she had typed phone books, police reports, and TV listings, and had even taken dictation, phonetically, in languages she could not speak. One of the worst jobs she ever had was the day she spent eight hours in a small, overheated room typing license plate numbers into a computer that kept shutting off and losing everything she had done; by the end of the day Janet had stored up so much anger and frustration that she stopped to complain to her supervisor on her way out. But Janet’s supervisor, a woman not much older than Janet, noticed the red ribbon pinned on Janet’s jacket and before Janet could even open her mouth to protest about the working conditions, the woman had pressed her hand lightly against the twirl of the fabric, and said she had lost her brother over two years ago. On her way home that evening, Janet stopped at a drug store and bought a spool of red ribbon and a box of safety pins.

Janet was aware that her ribbon would not feed anyone, would not end discrimination, provide funds or leadership or research for a cure for AIDS. But the things she saw, the words she could not speak, forced her to acknowledge her own emotions and fears. She cut a ribbon after reading the obituary of one of her favorite soap opera actors, cut another after noticing a homeless man with a sign that read he was ill, cut more when she passed a crowd of demonstrators protesting the rising price of medications. All these ribbons she began to keep in her purse; she could never give them out to other people. They were her ribbons. At one point, Janet joked there must be hundreds in her purse by now. Sometimes, when reaching inside, she hoped she might prick herself on one of the pins—a way of keeping her anxiety and sympathy tangible with pain. In the evenings she began cutting more and more ribbons, the radio announced that almost one-third of the African population was infected, another reporter said Asia was destined to become a wasteland, infected immigrants were now being banned entry into her own country. And her purse, now a large bag, really, became crowded with more and more ribbons. When Allen told her one afternoon that his buddy had died, a young man who had moved from Memphis to Manhattan to be a comic and whom Allen had taken care of for over seven months, Janet could no longer cut just one ribbon—Allen had also confided that he, too, was now infected.

And then one day Janet landed a role in a television commercial; she had been through three callbacks for a casting agent who was looking for a large woman who could tap dance in high heels. Janet was convinced that this was her opportunity, her chance, her moment to shine—really shine—as a performer. She arrived in Times Square, where filming was to take place, early one blustery spring morning. The wind was so irritating and chilly that morning that Janet huddled close to the archway of a building; garbage flew through the streets as fast as taxis. Janet waited for over an hour for the production crew to arrive, but when no one showed up, she went to a pay phone and called her answering service, only to find out that the director had died the evening before.

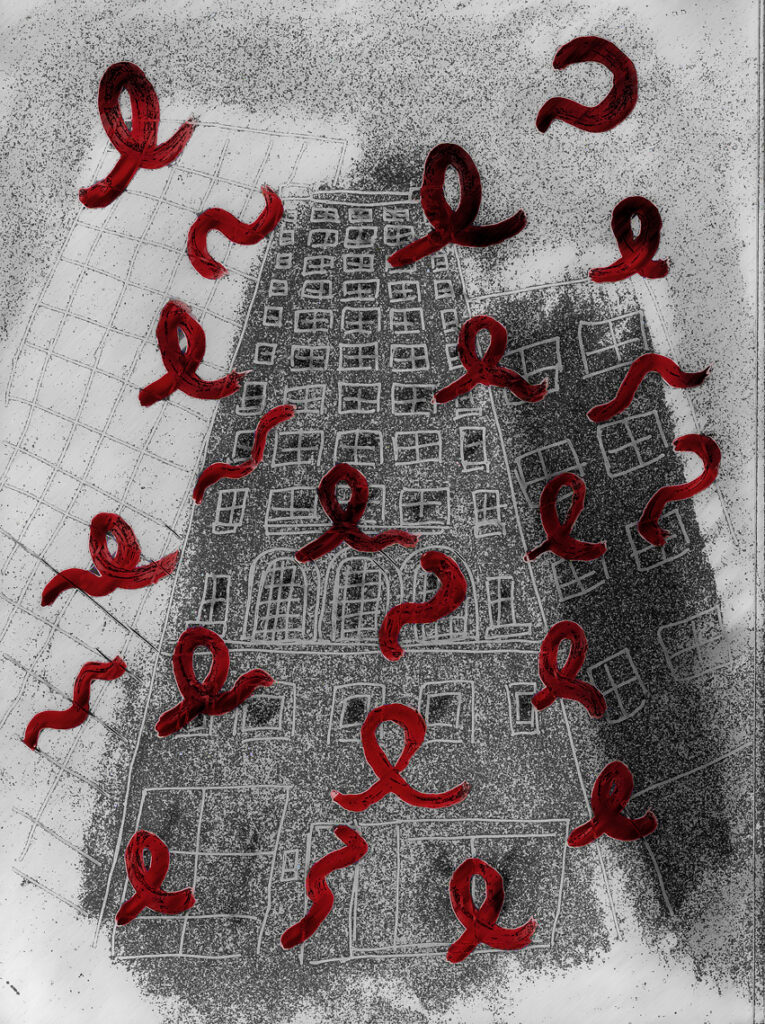

Wordless once again, Janet slammed the phone down, turned and walked toward the street, when the heel of her shoe missed the curb and she stumbled to the ground. Her purse, falling, slipped open and the wind lifted a river of red ribbons skyward like a startled flock of birds. Janet can still recall her frightened scream then—her anger and bitterness and hurt and frustration—all tossed into the sky with an anguish for deliverance.

Years later, when I met her at an audition, Janet told me she still searched the ledges of buildings for signs of her lost ribbons, fluttering in the wind like heartbeats.

_______________

“Ribbons” first appeared Art & Understanding, edited by David Waggoner (October/November 1993), p. 16-17. It was reprinted in Art & Understanding: Literature from the First Twenty Years of A&U (Black Lawrence Press, 2015), editedby Chael Needle and Diane Goettel, pp. . It was reprinted in Art & Understanding in August 2015, pp. 51-52 and online on August 30, 2015.