sketch of Rock Hudson

by Jameson Currier

ink on paper

20250124004

ROCK HUDSON’S VACATION

by Jameson Currier

When Rock Hudson died at his home in Los Angeles in October 1985 at the age of fifty-nine, his death created a transformation in the public consciousness of AIDS. Though he was the first major public figure to openly acknowledge that he was suffering from the illness, his last days were not without sensation and scandal. Speculation about his health began earlier that year when he appeared thin and frail during a taping of a cable television program hosted by his former co-star Doris Day. News reports during the summer had him collapsing at a hotel in Paris where he had gone to seek medical treatment and, soon thereafter, stories began to appear of the actor’s secret gay life in Hollywood. Not long after that, and only a few weeks before his death, Hudson released a statement at an AIDS fundraiser in Los Angeles that read: “I am not happy that I am sick. I am not happy that I have AIDS, but if that is helping others, I can, at least, know that my own misfortune has had some positive worth.”

Rock Hudson’s closeted gay life was not so secret to many people; like the sexual activity of many other gay entertainers (Liberace, Tony Perkins, and Montgomery Clift), Hudson’s homosexuality was generally known and accepted in the entertainment industry and gay community and, in the days before media “outing,” protected by the goodwill of both. Five years before his death from AIDS, I met Rock Hudson at the opening night party of a Broadway musical that I was working on as an apprentice publicist. The black-tie affair was at an Upper West Side restaurant near Lincoln Center. Hudson and his partner at the time were friendly with two women I worked for and I was introduced to the actor while he was seated at a table with his friends. One of my bosses was also seated at the table and as I leaned down to whisper a question in her ear, she turned to the man next to her and said, “Rock, this is my assistant.” I tilted my head and my eyes met his briefly. He smiled and I blushed, but before anything else could be said, my boss was standing up from her chair, pushing me out into the room, and giving me instructions to assemble the cast for a photograph. I was twenty-five years old that year and still a wide-eyed newcomer to New York City and the Broadway theater, and I did not let the opportunity pass to find some kind of a detail of the man who was an American icon which I could pass along to my friends and family. In my recollection of that night, I realize exactly how young and boyish I was, amazed simply by the actor’s towering height when he stood up from the table to leave the party. He was heavy-shouldered and six-foot four, and it was clear to me why he had made it in Hollywood—he still carried the handsome ruggedness that had made him a legend.

I am not even a minor character in Rock Hudson’s story. My meeting is not revealed as any anecdote in any biographies of the actor or the reminisces of his friends. He was never an idol to me. I didn’t think much of the films he made with Doris Day—there was always something so implausible to them—though I came to admire his films more in the years after his death, my favorite being Giant because of its epic quality. Rock Hudson was more a part of my parents’ generation than my own. And, as I recall, the year that I met him I was more enamored with the likes of Richard Gere and Jack Wrangler.

* * *

I must backtrack, however, to explain how I found my first job in the New York theater. After college, I moved from Atlanta to Manhattan with the dual purpose of attending graduate school and exploring my attraction toward men away from the scrutiny of my family and a hometown girlfriend. At New York University, where I was studying in the Drama department, I met my first gay friend in the city, an editor for a show business trade paper who was involved with a man who worked as a theatrical publicist and whose office was looking for a gofer. At the time, I was working a few hours a week as a telephone answering service operator used primarily by actors and the money I had taken out in loans for graduate school and my move north was quickly drying up. I thought a full-time job would help get my finances in better shape and, if the truth be known, the lure of working in the professional theater was too heady to resist. I loved the theater and desperately wanted to be a part of it. As a young man in Atlanta I had performed in summer stock productions, built sets for productions that played the Civic Center, directed large scale university productions, and toured shopping malls, high schools, and retirement homes singing with a cabaret troupe. My interview with the woman who co-owned the entertainment publicity firm was brusque and brief. I was hired on the spot, not because I was young and eager and smart and came with theatrical experience and a recommendation, but because I could spell and type without too many mistakes. (This was the era of carbon paper and bottles of white-out, three copies of everything typed at once.)

My daily duties at the new job included canvassing the newspapers and magazines that arrived in the office to find tearsheets and clippings that mentioned clients and shows the agency represented. I was so naive to the business of show business that I was not even aware that the city sported three daily newspapers or that there were such things as theater critics for television networks. I was taught how to fold a printed press release and the correct way to insert it into an envelope (headline side up), as well as how to seal only half of the flap on the back so that it would be easier to open by the recipient. The two co-owners of the agency, their one associate, and I sat in the same room with our desks facing each other so that our interactions were both effortless and annoying. I was to answer the phone before it reached its second ring, even if I was talking on another line. In the mornings, I made coffee before anyone else arrived, and at lunch time, if there were no pressing engagements for the owners with a producer or a reporter, I brought back pastrami or tongue sandwiches from the deli across the street. At night, I delivered ticket requests to the box office and messages to back stage doormen of the theaters where the office had shows running or clients performing. I typed names on envelopes, licked rolls of stamps, and carted bags of mail to the post office. It was one of those jobs that makes you question why you went to college in the first place, and so it was no surprise that I surprised myself and dropped out of graduate school because I felt that, well, as silly as it sounds, I was learning a lot more from working in the theater than I was by studying it in a textbook.

The main partner of the agency, the taller and older of the two women, was a mannish lady with a penchant for long mink coats and cowboy accessories—pointed toe boots, large engraved belt buckles, and Stetson hats. She had worked in the publicity business for more than thirty years and was full of a wisdom she felt necessary to direct toward others, particularly me, since I was in such close earshot of her booming voice. She had originally hoped to be an actress, but during rehearsals for a show she tripped on an imaginary flight of stairs and broke her collarbone and, as luck had it, ended up working in a publicity office where she began by typing, answering phones, and reading the papers, just as I was doing. Years of smoking had left her with a hacking cough and a deep, phlegmy rasp, which she would transform into a girlish tone when on the phone, trying to place a story with an editor or columnist. Her partner was a short, younger Italian woman with manicured nails and a teased hairstyle that made her pale face seem surrounded by a pair of large, dark raven’s wings. She was the novice publicist of the two owners, but the sharper businesswoman when it came to keeping the office running and the books balanced, and she spent hours refusing to take phone calls while she punched the keys of a calculator with the eraser tip of a pencil, the chug-chug-chug of its motor spitting out a long ribbon of paper.

I did not know that these two women were lovers when I first began working in the office, but it was not difficult to realize it after a day or so of their temperamental activity toward each other. They were big New York City creations—butch and femme—two self-made successes with a few family pedigrees thrown in, who shared an apartment on Park Avenue, a summer home in Connecticut, and a Mercedes Benz which they housed in either east or west side garages, depending on what side of town they were on at the time. In addition to their celebrity clients and Broadway productions, they had a Rolodex of high-profile friends, gay and otherwise, culled not only from the theater community but also from the fashion industry and the media. On New Year’s Eve, they threw an annual party where black tie was de rigueur and the likes of Rex Reed, Ann Miller, Lana Cantrell, Liz Smith, and Ethel Merman might be spotted and which, once I had paid my dues in overtime hours, I was also expected to attend, even though I was decades younger than most of the other guests.

I soon found that there were other young gay men working in the support industries of the Broadway community training to become company managers or house managers or press agents. Many of them became close friends when we began to gossip of the bizarre behavior of our employers or clients. We would swap tickets to each other’s shows the same way straight boys would swap baseball cards, and invite each other to opening night parties where we were not expected to work because we were not there for a client but could, instead, find ourselves locked in the embrace of a waiter in the stall of a downstairs bathroom for a few brief minutes of unexpected pleasure. It was a heady time to be young and gay and working behind the scenes. My story, however, and my years of working in the theater, is not that of someone who might have bartended at Studio 54 and found sex and drugs and a kind of celebrity for himself. It is the story of young man trying to understand a quirky business and who is always overworked, but aware that there is something special around the next corner that he has never before seen or done or known about, so he puts up with a little more than he might have if he was older and wiser. One night, for instance, I could make it inside the velvet ropes of Studio 54 and watch Andy Warhol’s coterie arrive because a friend of a friend had passed along a VIP ticket for that night, or another night, I might have to work and show up late at the theater to escort a press photographer into a backstage dressing room when Robert Redford congratulated the cast. The list of people I worked with and met is extraordinary for its time: Truman Capote, Kathy Bates, John Travolta, Eve Arden, Geraldine Page, Celeste Holm. Harvey Fierstein sent me a Christmas card. Elizabeth Ashley pressed a bandage against my forehead one evening after I had been injured while preventing a mugging. I once had a conversation with fashion designer Donald Brooks about the shoes I was wearing, a pair of gray suede platform shoes I had brought with me from Atlanta.

I’ve often avoided talking about my work in the theater because I felt that it could easily overshadow other aspects of my life. I am also somewhat embarrassed by this past obsessiveness of mine to belong and be a part of the theater, as well as the large amount of faith that I invested in it, hoping it would lead me to find myself, and which is why, when the novelty of this job wore off, I found that I was fighting a cynicism that was bitter even by New York standards. And it’s hard for me to admit, too, that I invested a great deal of time and energy trying to prove myself in a career in public relations that I soon discovered I was ill-suited for, whether it was in the theater or in a corporate environment. But that is not to say that those years were without fond memories or deeper discoveries about the direction I wanted to take my life. This, too, requires a bit of backtracking to explain.

* * *

By the end of my eighth month working in the publicity office, I began a three-year apprenticeship to join the union which represented the theatrical press agents and managers. It would be a long struggle for me to complete this because I had added up the pluses and minuses and found my heart was only half in the job. The apprenticeship was low paying, my bosses were jealous and vengeful and, while I continued being the office gofer, I was now juggling added responsibilities—writing press releases, setting up interviews, helping with the details of opening night performances and parties. Occasionally, there would be some other person brought in to help out in the office, but generally the budget was small and limited and the new help that was found was not necessarily interested in starting at a rung that was well beneath the basement floor. The associate who had found me the job was gone before I began my apprenticeship, and another associate packed up his bags when a show he was working on folded; another came in and found no problem with having the young kid do his work for him until it was time for him to leave as well, which left the agency essentially a three-person operation—the two older women (the bosses) and myself (the hired help who kept things going).

You may notice that I have not identified my employers by name. It would be years before I could acknowledge the damage to my self-esteem they had caused. Sometimes I think that I watched my youth disappear during this time—I always seemed to be working, dragging myself into the office on weekends to update a list of press contacts, repair a release I had fudged, or cover an event that was happening at a theater. I was also rock bottom poor. The money I earned from my apprenticeship was not enough to pay my rent. I often walked thirty blocks to work to save money that a subway fare would cost. Many days I skipped lunch. I was lucky that I answered the phone at work so I could hang up on the credit card companies tracking me down about missing a monthly payment without my bosses knowing how bad my finances were. As I look back on those years, however, I do see that I had dates and affairs (though no one serious emerged), and I explored gay life with my friends with the same curiosity I was investing in the theater. I went to the bars, beaches, and the baths, hitched trips with friends to Fire Island and the Hamptons, took buses to Provincetown and Atlantic City, but it always seemed that I had this job to come back to that I didn’t like but everyone else thought was wonderful. At times I wished I were older because then I thought I might be able to take my life more seriously and that others might regard me as someone other than the kid who worked in the office. For a while I grew a beard in hopes that it would make me look older, but the truth of it was, I looked, instead, like a boyish man impersonating an older one.

It was during this time that the two women I worked for began talking about a vacation that they would be taking around the upcoming end-of-the-year holidays. As a rule, they did not take vacations and loved to remind me of the fact when I dreamed of taking one myself. (There are no holidays in the theater, my bosses liked to tell me, only added performances.) The women did, however, maintain a three-day work week during the summer months, which essentially gave them four consecutive days at their country house. My work schedule during those summer months remained the same, however, always available and always on call and always trying to cover the fact that they were not in the office and not available to take anyone’s call.) Their upcoming holiday vacation was a Caribbean cruise on a private yacht with several friends, among them, as I recall, Claire Trevor, Ross Hunter, and Rock Hudson and his partner. At the time I thought it was a luxury to have them out of the office. They were eager to get away from the relentless pull of the theater and work and I was eager to see them go. My bosses were big drinkers and I imagined their celebrity friends to be as well, and when the day of their departure arrived, I visualized them lounging in recliners and sipping exotic drinks, attended by smartly dressed sailors and cabin boys. Bon voyage, I said to them on the phone. (And please don’t bother me while you are away.)

By then, the day they left for their cruise, I had fully recognized the mistake I had made in continuing with this publicity job, but I was also becoming aware of who I wanted to become. I had decided I wanted to be a writer. I did not see my own life as something to write about, so for inspiration I had become enamored with the idea of writing down the anecdotes of a friend who was an itinerant actress and musician and her travels with a small group of musical performers around the country. I was writing my first novel. I had started reading more to learn the structure behind fiction, started constructing my friend’s anecdotes into tales and then stories and chapters of a novel. And I could not get this idea or this desire or these characters out of my head until I had put them on paper. They pursued me down the street, waited with me while I delivered messages or asked questions about interviews and held press tickets in my hand. I recall one day being tugged away from my responsibilities in the office and toward the typewriter by one of my characters chattering away in my mind, and I started typing away at my desk, only to be asked in a suspicious tone by one of my bosses what the hell it was that I was so furiously at work on. I made up a lie, telling her that I was writing down some column ideas I had heard. (After that, in the office, I only wrote notes on scraps of paper while answering the phones, everything typed up later at home.)

So when my bosses left for their vacation with Rock Hudson, my immediate reaction was Hooray! I would have more freedom to write in the office. Of course, I was grimly wrong. Anyone in a small office (or large one, for that matter) who has ever covered for someone who is on vacation knows that it is usually twice the work load to assume. And, in my case, since I was covering for two absent bosses and trying to keep a business running, it felt even harder. The phones showed me no mercy during this vacation—I was constantly trying to retrace my bosses’ steps and cover their tracks—they had left me a list of clients who they did not want to know they were out of town. For two days I said that my bosses were at meetings, or at a rehearsal, backstage in a dressing room or not back from lunch. I hated lying. I wasn’t a very good actor, though I had managed to fend off Jerome Robbins and Bobby Short, among others, set up an interview with an actor and the Daily News, and help an out-of-town critic get press tickets. One small-time producer, however, wasn’t buying my lie and demanded to speak with my boss. After his third or fourth phone call to the office, when he stopped short of calling me an ugly name, I called the number of the coast guard that I had been given to use only for emergencies, and was patched through to the phone aboard the ship. A man who I assumed was the captain answered the line and I asked to speak with my boss (the butch one). While I waited for her to come to the phone, another man came on the line and asked, “What’s the weather like in New York?” It was unmistakably Rock Hudson. “Cold and stormy,” I answered, wondering if he was aware that I was also talking in metaphors. “Well, let’s hope it clears up before these two try to catch a flight home.”

The next thing I knew my boss was on the line. She was not in a good mood. I had obviously disturbed her for unimportant business. When I told her about the continuous calls from the producer, she let out a string of expletives. She sounded a bit drunk, but then she wanted to know everyone who had called the office while she was away. I went down the list I had been collecting. When I reached Jerome Robbins, she interrupted me and said in her little girl voice, “Jerry called? When did Jerry call?”

After I had given her an answer and the phone number Jerome Robbins had left, she reverted to the booming voice of an ogre that I had come to expect and received a dressing down because I should have known to call her about Jerome Robbins and not the small time producer.

As I moved through the remainder of the week with a frantic skill, it occurred to me that I had to find a way out of this “career” and change the direction of my life if I wanted to become a writer. Here I was in my mid-twenties, already facing a mid-life crisis.

* * *

During the second year of my apprenticeship, a small story was published on the back page of the first section of The New York Times. It was a news report about a type of cancer which was being found in gay men. I remember that it triggered a lot of thoughts and questions within me, foremost the notion if my desire to have sex with a man instead of a woman was biologically determined. At this point my story takes a similar route of other gay men in the city during these days. We worried, we read the news, we talked with friends and compared potential symptoms and confusions over the concept of “safe sex.” The theater community was one of the first and hardest hit by the first wave of the AIDS epidemic. I worked or attended early fundraisers at cabarets, discos, art galleries, theaters, and even a performance of the circus. I can remember when the phone would ring in the office and the conversation would be over a sudden change in casting because an actor was in the hospital or gossip about whether a certain director or producer might be ill. And many of these remarks were about people I knew and worked with on a daily basis.

The analogies that have compared the early years of the AIDS epidemic to trying to survive in a war zone were apt. Some days I felt it impossible to control the direction of my life because each piece of news that arrived was like another bomb exploding. And, as the truth became more grim, I carried around a depression that was difficult to shake off.

As it happened, the years passed and I completed my three-year apprenticeship and, not long afterward, I held a union contract for the office for the national tour of a play. While this new position allowed me some opportunity to travel to other cities and be outside of the office for days at a time, it did not remove any stress I felt from the job nor did it change my dislike for the profession of being a publicist. My bosses had also reached a change in their own thinking about my role in the office; they now expected me to bring in new clients, something that they had clearly not championed during my prior years nor had even bothered to discuss with me. When the national tour suddenly closed due to a lack of sales, I found myself back in New York and without a job because the office was without enough clients to support paying all three of our salaries. Within days, however, I was fortunate to find a job in the corporate sector, helping publicize, among other things, spray paint, motor oil, and fast-food hamburgers. This was another odd fit for me and when, a few weeks later, another theatrical contract was offered me in a different (though still small) entertainment publicity firm, I returned because I had not found a sense of self-confidence in any other place beside the theater. This, too, was another unfortunate decision for me to make; I went to work for a man I had known socially through my theater friends only to find out that he maintained a nervous, hyper-officious alter ego in the office. He made the butch and femme look like school girls.

Throughout all this I did not lose my desire to be a writer. I had long since finished the itinerant actor-musician novel, sent it out directly to a list of editors and publishers I had culled from press clippings, and had a large folder of rejection letters that did not so much disappoint me as to challenge me to become a better writer. And so my life in the city became a daily routine of odd contrasts, walking uptown to Times Square from my office near Macy’s, for instance, to cover an interview in a Judith Ivey’s dressing room, only to leave a few minutes later so I could sit in a small neighborhood park in Hell’s Kitchen and read a book that I hoped held some new clue for me on how to be a better writer, before the next duty at the theater called me back to Broadway or the sun set and I was forced to return to my tiny, expensive apartment. I refused to allow these two personas to overlap though it was often hard to keep them separate. I told very few people about my writing because I was afraid of being mocked and losing my passion to continue. And I was continuing to write about working in the theater, but now my stories were closer to my own experiences. I had written a short story about an actor who was trying to hide his illness, loosely based on a client I had known while I worked in the publicity office. I knew it wasn’t ready to be published, so I enrolled in a writing workshop that was being held on the Upper West Side, hoping to find a way to make it better.

This was the point I was at when the news of Rock Hudson’s death came to me. It wasn’t difficult to glance back and remember when I met him at the opening night party or talked with him during his Caribbean vacation with my former bosses. It almost seemed like an idyllic time in my mind; since then, the ground beneath me had shifted and trembled with and without my own uncertain steps. In the wake of Hudson’s death, the media would begin to change their coverage of AIDS. Elizabeth Taylor, his longtime friend, shocked that no one even wanted to mention the word, went into action and helped form The American Foundation for AIDS Research, at a time when then-President Reagan steadfastly refused to even acknowledge the crisis.

And in truth, I believe that Rock Hudson’s death did not change anything in my life that was not already on that course before it happened. But it did make me realize that what had been a part of my former job in the theater was not necessarily going to be a part of my future years in the city as a would-be writer. I never really lost my love of the theater, but during these early years of the epidemic, it just grew into a smaller and less important part of myself. AIDS would further impact me in ways that I could never imagine. It would take me a few more personal crises to find my own voice on the page and the way to the stories I felt I should tell. But one other thing that became resolutely clear to me at this moment: There was no going back to what had once been—things had changed and I had to find a new way to survive.

_________________________

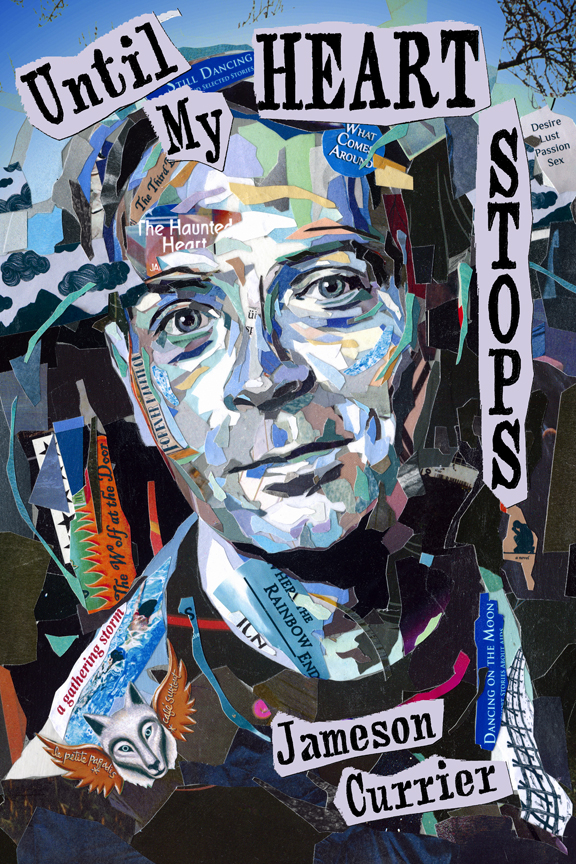

“Rock Hudson’s Vacation” was first published in 2014 in Assaracus 14, Joy Exhaustible, and reprinted in Until My Heart Stops, Intimate Writings by Jameson Currier (Chelsea Station Editions, 2015).