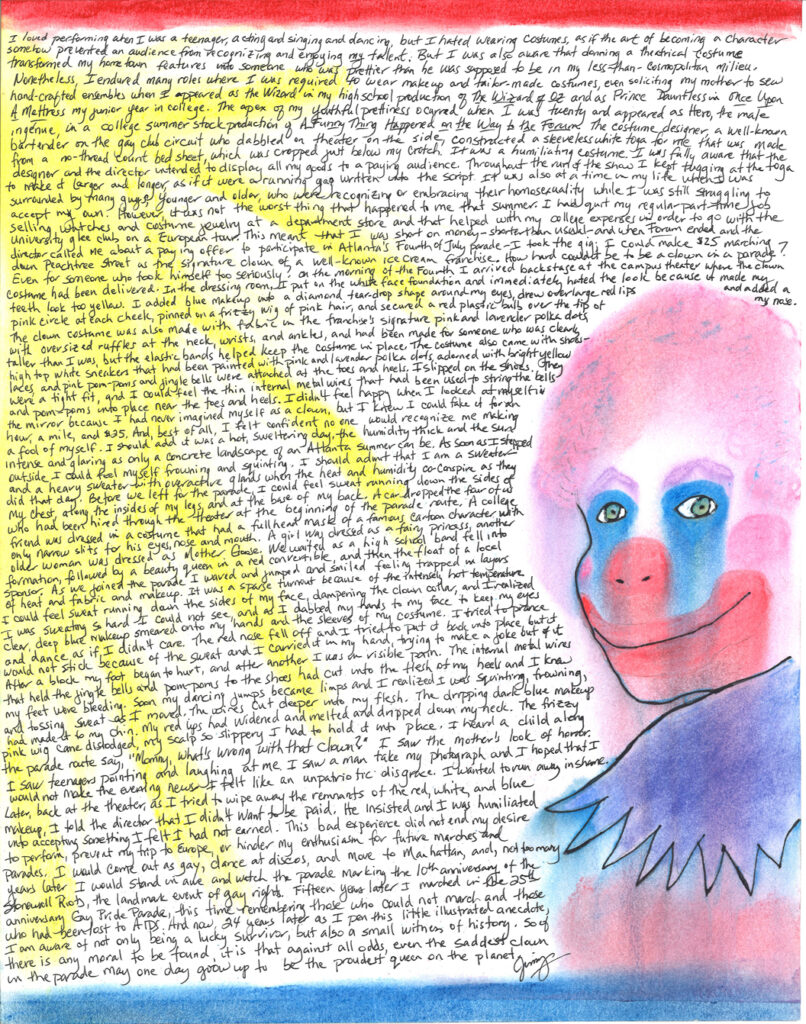

The Saddest Clown in the Parade

art by Jameson Currier

watercolor and ink on paper

20180925001

The Saddest Clown in the Parade

Jameson Currier

I loved performing when I was a teenager, acting and singing and dancing, but I hated wearing costumes, as if the art of becoming a character somehow prevented an audience from recognizing and enjoying my talent. But I was also aware that donning a theatrical costume transformed my hometown features into someone who was prettier than he was supposed to be in my less-than-cosmopolitan milieu. Nonetheless, I endured many roles where I was required to wear makeup and tailor-made costumes, even soliciting my mother to sew hand-crafted ensembles when I appeared as the Wizard in my high school production of The Wizard of Oz and as Prince Dauntless in Once Upon A Mattress my junior year in college. The apex of my youthful prettiness occurred when I was twenty and appeared as Hero, the male ingénue, in a college summer stock production of A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum. The costume designer, a well-known bartender on the gay club circuit who dabbled in the theater on the side, constructed a sleeveless white toga for me that was made from a no-thread count bed sheet, which was cropped just below my crotch. It was a humiliating costume. I was fully aware that the designer and the director intended to display all my goods to a paying audience. Throughout the run of the show I kept tugging at the toga to make it larger and longer, as if it were a running gag written into the script. It was also at a time in my life when I was surrounded by many guys, younger and older, who were recognizing or embracing their homosexuality while I was still struggling to accept my own. However, it was not the worst thing that happened to me that summer.

I had quit my regular part-time job selling watches and costume jewelry at a department store and that helped with my college expenses in order to go with the university glee club on a European tour. This meant that I was short on money—shorter than usual—and when Forum ended and the director called me about a paying offer to participate in Atlanta’s Fourth of July parade—I took the gig; I could make $25 marching down Peachtree Street as the signature clown of a well-known ice cream franchise. How hard could it be to be a clown in a parade? Even for someone who took himself too seriously?

On the morning of the Fourth I arrived backstage at the campus theater where the clown costume had been delivered. In the dressing room, I put on the white face foundation and immediately hated the look because it made my teeth look too yellow. I added blue makeup into a diamond tear-drop shape around my eyes, drew overlarge red lips and added a pink circle at each cheek, pinned on a frizzy wig of pink hair, and secured a red plastic bulb over the tip of my nose.

The clown costume was also made with fabric in the franchise’s signature pink and lavender polka dots, with oversized ruffles at the neck, wrists, and ankles, and had been made for someone who was clearly taller than I was, but the elastic bands helped keep the costume in place. The costume also came with shoes—high top white sneakers that had been painted with pink and lavender polka dots, adorned with bright yellow laces, and pink pom-poms and jingle bells were attached at the toes and heels. I slipped on the shoes. They were a tight fit, and I could feel the thin internal metal wires that had been used to string the bells and pom-poms into place near the toes and heels. I didn’t feel happy when I looked at myself in the mirror because I had never imagined myself as a clown, but I knew I could fake it for an hour, a mile, and $25. And, best of all, I felt confident no one would recognize me making a fool of myself.

I should add it was a hot, sweltering day, the humidity thick and the sun intense and glaring as only a concrete landscape of an Atlanta summer can be. As soon as I stepped outside I could feel myself frowning and squinting. I should also admit that I am a sweater—and a heavy sweater with overactive glands when the heat and humidity co-conspire as they did that day. Before we left for the parade, I could feel sweat running down the sides of my chest, along the insides of my legs, and at the base of my back.

A car dropped the four of us who had been hired through the theater at the beginning of the parade route. A college friend was dressed in a costume that had a full head mask of a famous cartoon character with only narrow slits for his eyes, nose, and mouth. A girl was dressed as a fairy princess, another older woman was dressed as Mother Goose.

We waited as a high school band fell into formation, followed by a beauty queen in a red convertible, and then the float of a local sponsor. As we joined the parade I waved and jumped and smiled feeling trapped in layersof heat and fabric and makeup. It was a sparse turnout because of the intensely hot temperature. I could feel sweat running down the sides of my face, dampening the clown collar, and I realized I was sweating so hard I could not see, and as I dabbed my hands to my face to keep my eyes clear, deep blue makeup smeared onto my hands and the sleeves of my costume. I tried to prance and dance as if I didn’t care. The red nose fell off and I tried to put it back into place, but it would not stick because of the sweat and I carried it in my hand, trying to make a joke out of it. After a block my foot began to hurt, and after another I was in visible pain. The internal metal wires that held the jingle bells and pom-poms to the shoes had cut into the flesh of my heels and I knew my feet were bleeding. Soon my dancing jumps became limps and I realized I was squinting, frowning and tossing sweat as I moved. The wires cut deeper into my flesh. The dripping dark blue makeup had made it to my chin. My red lips had widened and melted and dripped down my neck. The frizzy pink wig came dislodged, my scalp so slippery I had to hold it into place. I heard a child along the parade route say, “Mommy, what’s wrong with that clown?” I saw the mother’s look of horror. I saw teenagers pointing and laughing at me. I saw a man take my photograph and hoped that I would not make the evening news. I felt like an unpatriotic disgrace. I wanted to run away in shame.

Later, back at the theater, as I tried to wipe away the remnants of the red, white and blue makeup, I told the director that I didn’t want to be paid. He insisted, and I was humiliated into accepting something I felt I had not earned.

This bad experience did not end my desire to perform, prevent my trip to Europe, or hinder my enthusiasm for future marches and parades. I would come out as gay, dance at discos, and move to Manhattan, and, not too many years later, I would stand and watch in awe the parade marking the 10th anniversary of the Stonewall riots, the landmark of gay rights. Fifteen years later I marched in the 25th anniversary Gay Pride Parade, this time remembering those who could not march and those who had been lost to AIDS. And now 24 years later as I pen this little illustrated anecdote, I am aware of not only being a lucky survivor, but also small witness of history. So if there is any moral to be found, it is that against all odds, even the saddest clown in the parade may one day grow up to be the proudest queen on the planet.