by Jameson Currier

art by Jameson Currier

I’d started collecting the snow globes during a summer abroad in Europe before my senior year in college. I didn’t have room in my backpack for the usual souvenirs—beer steins, ashtrays, paperweights in the shape of the Eiffel Tower or the Coliseum, so I picked up a plastic snow globe in Frankfurt because it was cheap and small and light, and then got another one at the train station in Munich, then another in Vienna, and a few more in Venice, Florence, and Rome. By the time I was at the airport to return home, I had a dozen that I carried safely on board the plane in a plastic shopping bag. After then, whenever I traveled, I continued to pick up a snow globe as a souvenir—sometimes by special design at a hotel or museum gift shop, other times hurriedly at the last minute as I was running to the airport gate to make a flight. By the time Allan and I set up house together I had collected more than two hundred snow globes and when we adopted our son Justin I began to bring them back as gifts for him. At eight, his own collection exceeded more than a hundred and included snow globes from as far away as Tokyo, where I had gone one year for an economics conference.

I’d picked up this particular snow globe during a road trip upstate—my uncle had passed away and I had braved the bad winter weather alone on a four-hour drive to attend the funeral and check up on my parents. Allan had stayed home with the two children—his own job in the city and the kids’ school schedules made it too difficult to take the whole family for a midweek outing such as this. The services were somber and respectful, as they usually were in my family, and by the time I left my parents’ house for the drive back to my home, the icy rain had turned to snow. The drive was slow and exhausting—I’d had to concentrate harder because of the slippery and icy patches, so I stopped at a village midway through the trip that Allan liked to shop at when we made the trip with the kids in the warmer, summer months. It was a cluster of gingerbread Victorian houses and shops and restaurants, a mix of retail outlets, craft stores, and antique shops, nestled in a small valley among the mountains. The kids particularly liked the more unusual stores—the kite shop, the chocolaterie, and the toy store filled with nearly every kind of stuffed animal imaginable. I’d only stopped at the village to fill up the gas tank and stretch, but decided to eat something at the coffee shop and afterward stopped in the store next door, an antique shop full of eccentric and unusual curiosities, which is where I found the snow globe.

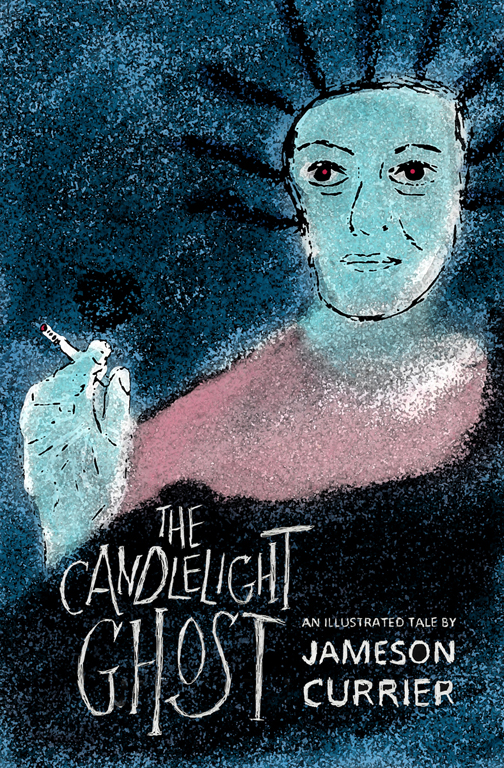

It was made of glass, not plastic, like a few of my special ones were—the one I had picked up in Aspen, the one my sister had brought back from Manhattan, and the one Allan and I got on our first vacation together in Mexico. This snow globe featured a ceramic Queen Anne Victorian house designed like many found in this village, a set of stairs leading up to a large front porch and a blue-painted front door with a stained glass window. The trim of the bay windows and gingerbread latticework were also painted in the same soft blue color, but the wood of the upper floors was of a deeper tone, and the dark gabled roof and black shingling gave the house a strong silhouette. But it wasn’t the house that I first noticed when I spotted the globe sitting on a table next to a stack of leather-bound books, but the flakes of snow stirring in the water; before I even reached out to pick it up and shake it, the snowflakes were swirling as if the globe contained its own storm.

I hesitated to purchase it. Allan disliked me bringing back glass-domed snow globes for the kids—the last one I had brought back from the Smithsonian had dropped and shattered in less than fifteen minutes back in the house and months later he was still finding little specs of glitter, which had been in the water, on the carpet. But I knew Justin would like it and so I bought it, and gave it to my son when I reached home, with a warning to be careful with it—he should find a permanent place for it and let it stay there and not keep picking it up. He took to it right away, calling it both “cool” and “spooky.” I’d arrived back home close to his bedtime, and he ignored the TV to study the snow and the three-story painted house. He placed the globe on a lower shelf of the bookshelf in the dining room, where he could sit on the rug and stare at it, much to the displeasure of Allan, who always liked to think that that room of the house was off limits except for special occasions. But the box of chocolates I had also stopped to purchase for Allan, along with the small stuffed toy turtle I found for Claire, our five year-old daughter, smoothed out my partner’s cranky disposition.

“Tom, did you see the lady in the top window?” my son asked while Allan told me to get him upstairs and ready for bed. Justin was on his knees, his eyes close to the glass and from where I stood in the doorway the snowflakes swirled steadily inside as if cast by an enchanted spell.

“What lady?” I asked, leaning down over him. I vaguely remembered seeing something different about one of the upstairs windows when I had picked up the globe in the antique shop—a faint glow, as if there were a table lamp or candle inside the room.

“On the second floor,” Justin said. “You can see her dress.”

I looked at the upper floors of the house through the swirling snow and Justin tapped the glass globe lightly with a finger where he had seen the shape of the woman. At the end of a row of darkened windows there was one that was distinctly white, and in the background of the room was the silhouette of a woman’s dress. “There’s someone beside her, too,” I said. Another small form was barely discernible, as if it were a child’s head.

“Where?” Justin asked. He looked deeper into the water and the snow and the house. He sighed when he spotted the smaller figure, then said, “No, there’s two kids. She’s got two kids beside her. Maybe she’s putting them to bed.”

That was my cue to become a father myself, urging Justin to go upstairs to bed, but instead I looked into the snow to find the three figures. “What makes the snow move so fast?” Justin asked me.

“You must have hit it,” I said.

Justin protested, saying he hadn’t touched it at all. The snow was falling on its own. This was when I told him it was past his bedtime, and I followed him upstairs to his room, kissed him good-night, and checked on Claire in her bedroom. She was already asleep in one of her awkward, contorted positions, half on and half off the bed. I was the last to go to bed that night—I watched the late news and Leno’s monologue, then made sure the front and back doors were locked, the security system was activated, and all the lights were off, and went upstairs. It had been Allan’s idea to adopt children and move to the suburbs to better raise them, and at first our presence in the neighborhood had unsettled a few of our stodgier neighbors. We’d suffered through a period of egged cars and flattened mailboxes. But we weathered that as we often weathered the bad weather, though I’d always found it queer that I was more suspicious of everything living here, in middle-class America, than I had ever been on my own in a two-room tenement in the downtown gay ghetto.

In the bedroom, Allan was sleeping on his side, and I settled in around him and fell easily asleep. It wasn’t much later—or seemed to be not much later—that I heard a noise downstairs. It sounded like the back door of the house opening and shutting—the particular sounding whumpf that door had. Our house was a typical kind of suburban ranch style—a long first floor leading to a staircase and a smaller second floor with bedrooms and baths. Next I heard the kitchen floor creak like it always does when there’s too much weight passing on top of the floorboards. I lay still, trying to imagine if it could be one of the kids. Lately, they had become sound sleepers, not waking up during the night, and whenever they did, whenever they were scared or hungry or not feeling well, they came to our bedroom first, never going downstairs to the kitchen. When the idea occurred to me that we might be being robbed, I began to think of what kind of defense I might have upstairs to use against intruders—an industrial flashlight that I kept in the closet, a blow-dryer in the shape of a gun, the ceramic base of the lamp on the table beside the bed. I got up and easily found the flashlight on the closet floor, then went to the hallway to listen more closely.

The sound had stopped and I waited a minute before heading downstairs. I made my steps on the staircase heavy and noisy; in case there were intruders, my goal was not to surprise them but to make them flee. I walked heavily into the family room, where only a few minutes earlier I had been watching TV, and flipped on the overhead light, but found no one, and nothing was disturbed. Then I went into the kitchen to check the back door.

I found no one in the house, nor anything suspicious that might convince me that there had been intruders—the back door was safely locked, the sliding glass door which led to the outside patio was locked and closed, the house’s security system was still on and armed. As I was turning out the downstairs lights to return upstairs, I stopped in to check on the status of the living room and dining room. No one was there, either, though when I entered the dining room I felt a sudden blast of cold air, as if a window was open. Outside there was a howling winter wind, and I rationalized a good strong gust must have hit the house and unsettled the back door, the kitchen floor, and the air in the dining room. I checked the windows but they were all securely closed and locked, and then I went back upstairs. As I was passing by Justin’s room, I thought I heard him crying. I stopped and looked in—he was sleeping on his side but trying to say something in his sleep, which sounded like whining. He awoke just as I came toward him.

“You’re okay,” I said, reaching out to my son. “It must have been a bad dream.”

“I saw a woman,” he said. “She was trying to say something to me but she couldn’t—she had holes in her face.”

“It was just a bad dream,” I said again.

I waited till Justin was calm and back asleep and then I checked on Claire and went into my bedroom. Allan was sleeping in the same position Justin had been in and now he was mumbling something in his sleep. He awoke as I slipped into the bed.

“What is it?” I asked him.

He looked at me as if I had been in his dream, too. “Just a dream,” he said. “I thought there was a woman in our room.”

“A woman?” I asked him. “What kind of woman?”

“She had a strange face,” Allan said. “Full of holes.”

I didn’t say anything about Justin having had the same dream. In fact, I was a little slow in connecting the two similar nightmares—by now I was relieved that there was no intruder in the house and tired and exhausted and thinking how I would feel the next day at work if I didn’t get to sleep soon. I didn’t even tell Allan that I had gotten up because I had suspected there was an intruder in the house. “It was just a dream,” I said to him. “I have to get some sleep or it will be hell tomorrow.”

In the morning I found Justin sitting on the floor of the dining room, looking at our newest snow globe again. “They’re gone,” he said when he saw me standing at the doorway watching him. “The lady and the two kids.”

“It must have been the snow,” I said. “Or maybe there was something stuck to the side of the house. Some of the old globes have dust in the water. Maybe it was just dust.”

In the kitchen I found Allan in a particularly agitated mood. “I didn’t sleep well last night,” he said. “I kept having that same dream over and over.”

I thought he was going to say something about the woman with the holes in her face, but he said, instead, “I kept trying to get to Justin and Claire and I couldn’t. I couldn’t seem to get to them, even though they were near me. They were frightened and I knew something was going to harm them.” He sighed, and then yelled to Justin in the other room. “If you don’t eat something right now, young man, I’m not going to put any cookies in your lunch bag.”

I left Allan to find Claire in the den watching TV. She was half-dressed in her pajamas and school outfit and talking to the rag doll she had in her lap. Our morning routine was that I would get Claire ready and Allan would tend to Justin, our more hyperactive child. I would drop off Claire at kindergarten, a longer drive, and Allan would take Justin to the elementary school on the corner. Two kids, two cars, two parents—each with their own destination.

“Who are you talking to?” I asked Claire when I turned off the TV.

“Sally said she had a doll just like this,” Claire said.

“Who’s Sally?” I asked.

“Ben’s sister,” Claire answered.

“Who’s Ben?”

Claire laughed as I lifted her off the floor and carried her in my arms out of the room. “He’s Sally’s brother!” she squealed.

On the drive to Claire’s school she continued to talk to her imaginary friends. She was in the backseat of the car, bundled up in a puffy pink coat and ski cap and buckled into a car seat so I could see her through my rearview mirror.

“Where did you meet Ben and Sally?” I asked Claire.

She giggled again and said, “They’re waiting for their mommie!”

“Their mommie?” I echoed from the front seat. “Where’s their mommie?”

“She went to look for the other mommie!”

“Oh,” I answered her, as if it all made sense.

At the school, Claire asked me if it was okay for Ben and Sally to wait in the car for their mommies. I tried not to show my annoyance—I thought this silliness had gone far enough, but I didn’t want to scold Claire and send her off to school agitated. “Sure, they can wait,” I said.

“They said it’s safe in the car,” Claire said while I was unbuckling her from the car seat and helping her to the ground. “They don’t think the bogeymen will find them in the car.”

“The bogeymen?”

“Yes,” Claire said. “That’s where their other mommie went—to find the bogeymen.”

“That’s enough, Claire,” I finally said, and we walked together into the school building. “Don’t worry about Ben and Sally,” I said when we had reached the door of her classroom. I had had a change of heart about the imaginary friends—or, rather, I had stumbled into the mental conundrum of what exactly a parent should say to a child who had an imaginary friend. I thought that perhaps the gentler approach was a better one. “Don’t try to eat the crayons,” I said next, as if I had to find something parental to say.

“We’re not coloring today,” she said.

I kissed her on the top of the head, watched her enter the classroom, and then walked back to my car. For a moment I expected to find Ben and Sally seated and waiting for me, but by the time I reached the highway I had forgotten about my daughter’s friends, thinking, instead, of the confrontations ahead in the office.

When I got home from work that evening, Justin was again in front of the new snow globe in the dining room.

“Somebody’s on the steps,” Justin said.

“What do you mean?” I asked him. My tone was short and annoyed. I had had a stressful day grappling with an analyst’s report that had been released that morning, and it had affected my work schedule and meetings throughout the day—one person after the next complaining about the report.

“There’s two guys on the steps that go up to the front door,” he said. “They look like they’re carrying guns or something.”

I loosened my necktie and squatted beside my son, looking over his shoulder and into the glass globe. Sure enough, barely visible through the snow, there were two tiny figures waiting on the steps of the house and carrying something in their arms. “Looks like rakes,” I said. “Or brooms. They were probably there yesterday and we just didn’t see them.”

“They weren’t there yesterday,” my son protested. “I know they weren’t there yesterday.”

I watched the swirling snow inside the globe. Neither of us had touched it and I felt the defensive pang of a parent confronted with something he knew he could not explain. “Go wash your hands,” I said to my son. “Allan’s ready for supper.”

At the dinner table there was no further discussion about the globe, the two strange men, Claire’s imaginary friends, the bogeymen, or the nightmare woman with holes in her head. Allan had turned on the TV that sat on the counter and the kids sat watching a program of funny home video clips. Tomorrow was Saturday and Allan was eager to find some activity to keep the kids occupied—we were in the lull between the end of the winter session of karate and ballet classes and the beginning of the spring ones.

“The weather’s supposed to be lousy,” I said. “We could take them to the movies.”

Allan mentioned that he would check the movie schedules and then added he might take Justin to get new shoes—he was close to growing out of the new ones he had gotten a few months ago.

After dinner, Justin found me in the den reading the newspaper. “They’re at the door,” he yelled at me. “The two guys are at the door now.”

“It must be a piece of dust that’s floating around,” I said.

“No, Tom, come check it out,” he said. “They’re there. At the door. And they both have guns.”

The tone of his voice both alarmed and irritated me. “Justin, if you keep this up, I’m going to have to put it away.”

He seemed to take note of my annoyance—finally, I acted and sounded like a parent, the kind of parent I never wanted to be. I remembered my father displaying the same behavior toward me when I was a kid and he didn’t want to be disturbed. I tried to find a better way out of it and be a better father to my children. “Why don’t you and Claire watch one of your videos?” I said to him.

My suggestion worked. Justin abandoned the snow globe and the kids watched Monsters, Inc. for the three-hundredth time, then Allan and I settled them into their beds upstairs. Again that night I stayed up later than Allan—watching the late news, the Leno monologue, and then the beginning of a behind-the-scenes documentary on the movie Poltergeist before I fell asleep on the couch in the den. I woke when I thought I heard the sound of shattering glass—it sounded as if the sliding glass door had fallen off its runners and shattered on the cement ground of the patio. I got up to check on it and heard again the distinctive squeak of the kitchen floor. My heart was rapidly beating in my chest as I approached the kitchen—we either had intruders or someone in the kitchen had hurt himself. I didn’t bother to reach for any kind of weapon—I was not thinking that fast this evening—only reacting quickly to find the source of the disturbance. When I walked into the kitchen no one was there—the back door was locked, the sliding glass door was in place and perfectly fine, undamaged. It, too, was locked. I looked out the glass door to the patio, thinking I might see someone out there on the fringe of the lawn, but there was nothing except the bare, cold winter night—clumps of snow that had never melted surrounding the posts of our backyard fence. I checked the doors again, activated the security alarm, then went and turned the TV off, ready to go upstairs, thinking I must have heard something in the TV show or a commercial that had made its way into a dream I was having.

Before I went upstairs I stopped to check the living and dining rooms and, again, I felt a bitter blast of cold air surround me. I flipped on a lamp and leaned down and looked at the new snow globe on the lower shelf. There were no figures in front of the house but I noticed now that the pale blue front door—which had always been closed before—was open. On the second floor, where the night before I had seen the light in the window with three figures, the window and the room behind it were dark. But the snow continued to swirl inside the globe. I felt the sides of the bookcase, wondering if I might feel an undetected vibration of the house, but I sensed nothing except my own bafflement. I stopped looking and stretched my back, thinking I was just tired, and tried to shake the heavy concentration from my mind. I felt I was just imagining it all, so I turned off the light and went upstairs to bed.

But again it was a restless night for the family. This time Claire woke up crying, saying she had seen a woman with an ugly face. Allan settled her down, only for her to wake up a few minutes later and crawl into our bed between us. This time I fell into my own version of the nightmare. I dreamed that I saw two men breaking into the house—not our house, but the house in the snow globe. They had entered through the pale blue front door, jimmying it open. They had found a woman first, in one of the ground floor rooms, gagged her, and bound her to a chair behind a desk. Then one of the fellows, a short, dark-haired man, brought two children into the room—kids who looked frighteningly like Justin and Claire. The men kept the woman and children bound for a long time, as if they were waiting for someone else to arrive. In the dream I walked into the room and was bound and gagged myself. I watched as the woman was shot first—blasted through the face with a shotgun. Then the children were shot. I had been made to witness it all. I woke, sweating through the T-shirt I had worn to bed, when the shotgun was pointed at me in the dream.

The next morning I didn’t tell Allan or the children about the dream, but on my way downstairs to eat breakfast I stopped to look at the new snow globe. The blue front door of the Victorian house was closed, the windows on the top floor were dark, and where I and my son had once seen figures on the front steps, now there was no one. But the snowing had not stopped inside the globe. In the kitchen, I was about to confess my bewilderment to Allan, but he complained first about being unable to sleep again the night before. While Claire and Justin were eating their cereal, he whispered to me his own version of the nightmare I had had. He had dreamed he was in an old house and had been reading a story to the children when he heard something downstairs—a crash, as if a window pane had been shattered. He had stepped outside the room to check on the sound but had found nothing, and had gone back to reading with the children when he heard footsteps creaking on the old stairs of the house. Again, he went to check on the sound and found nothing. “We were asleep when they came into the rooms,” he said. “They brought us all to one room and shot us. We had to watch them shoot the children.”

“It was just a dream,” I said, not daring to tell him of my own nightmare or any of my other suspicions.

Claire interrupted us by asking, “Allan, can Ben and Sally play in my room?”

“Who are Ben and Sally?” Allan asked.

“My friends!” Claire answered.

“We’ll have to ask their mommie first,” Allan said.

I would have explained to my partner that Ben and Sally were Claire’s imaginary friends and he would have to ask their imaginary mother, but the phone rang and I went to answer it. It was one of my bosses from the office, explaining that the senior managers had held a special Saturday morning teleconference to respond to the damaging analyst’s report, and I was expected to be in the office later that day to help formulate the company’s response. I had taken the cordless phone and walked to a corner of the kitchen, away from Allan and the kids, and when I realized that I was being asked to leave my family for the day I turned and looked at Allan, as if to let him know I was going to have a change of plans. That was when I felt the cold air surrounding me and I saw a ghostly shape of gray haze standing beside Allan. “I can’t be there,” I suddenly told my boss. “I can’t do it. I’m having a family emergency.”

I hung up the phone and faced the perplexed stare of my significant other. The gray shape beside him had disappeared and I said, “Get the children ready. We’re all getting out of the house for a while.”

“What’s going on?” Allan asked me.

“I’m not sure,” I answered. “But I don’t think we should be in the house.”

The kids were ready before Allan and I were, and on my way out to the car, I stopped in the dining room and placed the new snow globe in a paper sack. When I got in the car, I handed it to Allan with the instructions, “Don’t open it. Don’t look at it.” I’m not sure why I said that, except that perhaps I feared he would see something he had only imagined happening. As I backed the car out of the driveway, I noticed Claire, in the backseat, whispering to someone.

“What is it?” I asked my daughter. “Who are you talking to?”

“Nobody, Tom,” she said, her eyes wide and full of fear.

I knew she was lying. I stopped the car and said more sternly, “Tell them to get out of the car.”

“Why Daddy?” Claire whined.

“Tell them to get out.”

There was a confusing scene—Allan asking what was going on, Claire bursting into tears, Justin crouching against the other car door. I hopped out of the car and opened the door next to Claire. “Tell them to stay with their mommie,” I said.

“No, Tom-eeee,” Claire said. “They don’t want to.”

“Tell them.”

Claire mumbled something through her tears, and once I was satisfied that she had left her imaginary friends behind I started the car and we were headed away from the house. The kids had never seen me act this harshly before, and I had a palpable fear that these moments would be the ones they would remember about their childhood and their overbearing, strict parent. Allan was confused and irritated with me and tried to play good cop to my bad cop, but the trip to the village was longer and more frustrating than I had anticipated. There was an accident on the highway, one of the lanes was closed for construction, and the exit was clogged with weekend tourists hoping to shop at the discount outlet stores that ringed the area. I parked our car in the parking lot of the coffee shop where I had eaten only a few days before. I told Allan that it was best if all of us stayed together in the antique store. The kids didn’t understand this protective urge of mine—Claire had no interest in the store, and she let out a high-pitched whine as we passed by the toy store. Allan was now pressed into the role of being the stern parent. He pleaded with Claire to behave better, while Justin looked on, his face dismayed and unhappy.

In the antique store I found the old man who had sold me the snow globe. Allan had managed to keep the kids nearby and distracted, looking through a rack of vintage comic books, while he remained close enough to overhear my question. When I lifted the snow globe out of the bag, I asked the man, “Can you tell me something about this? I bought it here a few days before.”

“That’s the old Hartman-Monroe house,” he said. “It was the first of its kind in the village. They tore it down more than thirty years ago.”

“Tore it down?” I asked him. “Why?”

“Spooks,” he answered, smiling. “Said it was haunted.”

“Haunted?” I said. “By whom? What happened?”

The old man walked away from the counter, stepped into the aisle near Allan and the kids, and came back with a small paperback book—a tourist guide to the area. “It’s all right here in this section,” he said. “The Monroes—the family that built the house—were murdered one night in 1932. By drifters. It was the Depression, and the legend goes that the drifters had helped build the house and came back to ransack it for money out of a safe. Mr. Monroe had died the year before. Freak accident in the snow; his sister had moved into the house to help his widow take care of the two kids. The two fellers shot the entire family. There was a nationwide search for the killers. When they were finally caught, they were tried and both of ’em got the chair.”

I took the book from the old man and asked, “Are there any more details in here?”

“Sure, lots more,” he said. “Clippings from the newspaper. A few photographs. Lots about the Hartmans.”

“The Hartmans?” I asked.

“The family who owned the house in the 1950s,” he said. “Same kind of thing happened to them. Mrs. Hartman divorced her husband and a lady friend moved into the house to help her raise the kids. Lots of gossip about them two women. Then, two drifters came and killed the whole family one night.”

I looked over at Allan and saw that he had gone pale. I told the old man that I wanted to buy a copy of the book, and as he was ringing up the sale, I asked him, “Who made the snow globe?”

“The snow globe?” he answered. “Not sure about that. It’s been here for years—it was part of the inventory when I bought the shop about six years ago. No one never wanted it until you came along.”

Allan and I agreed that it was best to keep the kids occupied and entertained while we discussed what to do next. Somehow it was late afternoon when we had finished shopping through the stores and I had read in the guidebook what had happened to Melissa Hartman and her friend, Dianne Sanderson, and the two children. Two men, drifters, one just out of jail and the other waiting for him, had driven past the house one day and decided to rob it. During the robbery, the man just out of jail lost his temper, and killed the family in the downstairs parlor. The coroner had established that Mrs. Hartman and Miss Sanderson had watched the drifters kill the children first, then Mrs. Hartman had watched her companion shot. All of the family had died from gunshots through the head. The children were ages six and eight—a girl named Sally and an older brother named Ben.

We stopped to have dinner in the coffee shop before the long drive home—the kids were restless and hungry. While we were ordering it started to snow outside, not a light snow, but a sky full of thick, fat snowflakes that quickly coated and covered everything in sight. I knew this would mean a long and difficult drive home, and since I was the one of the four of us facing the large picture window, I sat and watched the snow come down harder and harder on the parking lot of cars and the old Victorian shops, feeling anxious and uneasy. “I don’t think we should drive in this,” Allan said first. “How can we see?”

“We’ll give it a bit,” I said. “Or there’s a motel near the highway if we need to stop.”

“That’s too far to drive,” he said. “We should try to find something here. There was a place across the street in one of the old houses.”

When the waitress came and took our order, Allan asked the name of the guesthouse across the street, then he used his cellphone to see if a room was available. The clerk told him one room was left and Allan asked if it was big enough to accommodate a family of four. The man put Allan on hold while he checked on portable bed arrangements, and when Allan hung up he seemed relieved to have it all worked out so quickly, telling me that we could stay at the inn across the street until it was safe to drive back to our house.

The kids were delighted with this plan, and their spirits improved. Claire thought this meant that she would be able to sleep in the toy store, and Allan explained to her that we were going to be across the street, and that the store would be closed. Claire was disappointed, almost to the point of tears, but after dinner we stopped in the store and bought the kids books and a board game to keep them amused. This seemed to redeem us once again in the eyes of our children.

The inn was not a duplicate of the house in the snow globe, but it was eerily similar—a large front porch, bay windows, and a front door with a tiny stained glass window. Electric candles were glowing in all the windows, and the gabled roof and gingerbread trelliswork had been covered with tiny icicle lights, so that through the falling snow it looked as if we were approaching an enchanted cottage. Inside, the rooms of the inn were painted in frosty gumdrop colors, but they failed to hide the slightly musty odor of the aging wood and antique furniture, and I greeted every suspicious creak and crack as if it were a bad omen.

It took me a long time to settle in the room. I kept looking out the window at the snow, hoping it would stop, or just lessen, and we would be able to leave the inn and make the two-hour drive back to our home. I didn’t feel safe in the inn. I’d had this crazy notion running around my mind that we were actually staying inside that house—inside the Victorian house in the snow globe—and that somehow we had changed homes with the ghosts and now we were going to be assaulted. I didn’t tell Allan this, of course, but he knew I was jittery and uneasy. Once the kids had calmed down and were watching TV, he picked up the guidebook and began to read about the village, asking me questions or reading passages out loud. I had kept the snow globe in a bag in the closet, and once Justin had fallen asleep and Claire was just about to drop off, I went to the closet to get it to study again.

“Do you really think that Claire saw the kids?” Allan asked me, looking up from his reading.

“I think so,” I said. “Because she did leave them behind. But it’s strange. Look at the picture of the Monroes, the family before them. Is that the woman you saw in your dream?”

Allan flipped through the pages of the guide and found the picture of the Monroe family, looking at it silently without commenting. Finally, he breathed in a nervous gasp of air and said, “It was a dream. It wasn’t real.”

“But it was her,” I said. “I’d swear in a court of law that I had seen her before.”

“Is that what spooked you? In the kitchen this morning?”

“I sensed something that told me we had to get out of the house,” I told my partner honestly. “I can’t say that I believe in ghosts.”

He closed the book and said, “It’s all really silly and coincidental. I used to read ghost stories all the time when I was a boy. They never frightened me, because I always felt there was a reason for the ghost; like it was in the house because the spirit wasn’t settled into death—murdered, or hidden inside a wall, or buried beneath the floor of the basement. Sometimes they were after revenge, or trying to warn another generation about trouble.” When he stopped talking his expression froze, as if he were imagining confronting a ghost, then he sighed and said, “It will all work out.” This admission seemed to calm him, and I knew he was ready to sleep.

There was nothing unusual now about the house in the snow globe. The second floor windows were dark and shut, the front door was closed, the figures I had seen on the steps and the front porch were no longer there. But the snow continued to swirl inside the globe, and its movement kept me wondering about what could happen to us next. I set the globe down on the night stand and turned out the lamp beside the bed. The light from the TV set flickered eerily through the room, until I found the remote control and turned it off when I felt sleepy. I didn’t fall asleep quickly, however. The creaking and cracking sounds of the inn shifting under the weight of the falling snow kept me awake and nervous.

The ringing sound of a phone awakened me sometime later, when I had managed to drift into a light dream. It had a faint, muffled sound to it, as if it were in another room or hidden away somewhere. Allan, too, awoke when he heard it, and he stumbled out of the bed to the chair on the other side of the room, where he had left his coat with the cellphone in the pocket.

After a few seconds he turned to me and whispered, “It’s the alarm company. Someone’s broken into the house.”

I took the phone from him and we went into the bathroom together and turned on the light, where I could wake up and talk calmly, without disturbing the children. The man from our home security company said that a windowpane on our back door had been broken and the house entered. The police had arrived quickly and nothing seemed missing except the downstairs TV. We talked quite a bit with the security representative, as he asked questions about where the TVs were located in the house, if we had a computer or stereo equipment, and what kind of valuables we might have owned. Allan had nothing of real value except a Rolex watch he never wore, and it sounded like the robbers were in search of quick cash. The man assured us that the house was again secure and locked—a board had already been placed over the broken glass pane of the door. Before I hung up, I asked the rep how heavy the snow fall was in the area. He seemed stumped for a moment, and there was the sound of empty air on the phone line; then he said, “It’s not snowing here. But it’s cold. Your house is really cold. You should keep the thermostat a little higher.”

The next morning the snowing had stopped in the village and I was anxious to return home, but Allan said he didn’t want to rush the children, didn’t want them to arrive at the house frightened and worried. We ate again at the coffee shop across the street, and let the kids play a few minutes in the snow-covered field above the parking lot, before brushing them off and settling them in the car. Throughout the morning I had checked the snow globe—looking at the top floor windows, the front door, the steps—but saw no sign of any intruders or inhabitants, actual or imagined. It was if, having discovered the secret of the snow globe, the power of its suggestion had stopped.

It was a long drive home, but the kids were in a cheerful mood, Allan keeping them talking and happy as the roads cleared and the mounds of snow disappeared into icy patches and then the wet flat stretch of the highway. Before we set out from the village, Allan and I agreed that he would drop me off at the house first to check things out, and he would take the kids with him to the grocery store. At the house, the back door windowpane was boarded up with a small square of wood, just as the security rep had said. There was still a small amount of glass on the kitchen floor, and I swept that up, then made my way through the other rooms checking to see if anything else might have been stolen. Everything seemed to be in order except for the missing TV, though the house felt slightly askew, as if things had been moved and put back at a slightly different angle than before. When Allan and the kids arrived home, I was on the phone with the rep again, thanking him for his help the night before.

Late that afternoon, two detectives visited the house. They asked a few questions about the break-in—where we were at the time, what was taken. Then they asked if they could dust for fingerprints from the back door and the stand where the missing TV had been placed. Justin and Claire were upstairs in their bedrooms and Allan was on the computer in another room. Only while one of the men was dusting the glass did I find out the real purpose of their visit: the detectives were hoping that fingerprints in our house might match a crime scene a half mile away. Another house had been broken into the night before and the family had been murdered—a man, his divorced brother, and his two sons. According to the detective, they already had two suspects in custody—two men just released from prison, but no confessions yet from either suspect.

The news stunned me and I asked him to please not repeat the story to my partner or the kids—it would only spook them. “We’re always a bit nervous because we’re not your typical suburban family, either,” I said.

I stayed with the detectives while they went about their dusting, but didn’t mention that I had abandoned the house with my family the previous day. I still couldn’t admit that I believed in ghosts—good or bad—and I knew it would be difficult to explain that a supernatural force had frightened us into leaving and in doing so, might have saved us from the fate that had befallen the other murdered families. After the detectives had left, I realized that I had left the snow globe inside the car, and I went outside to find the bag still beside the driver’s seat. I took the globe out of the car, out of the bag and lifted it into the sunlight. The snow still swirled magically around; and there in the top window was the silhouette of a woman, now bent as if she were looking out the window at the snow falling on the roof and steps and lawn. Somehow I knew when I saw her there that things were safe with us, that no harm would find us in our house, and that this was how the snow globe was supposed to be.

I put the snow globe on the shelf in the dining room where Justin had originally placed it when I first brought it home. It stayed there safely through the years, undisturbed, the woman in the window watching over our family.

___________

“The Woman in the Window” first appeared in All Hallows, the journal of the Ghost Story Society, edited by Barbara Roden (Issue 42, Spring 2007), pp. 117-128. It was also published in the anthology of GLBT speculative fiction, Wilde Stories 2008, edited by Steve Berman (Lethe, 2008), pp. 17-35, and was included in the author’s collection The Haunted Heart and Other Tales, published in paperback by Lethe Press in 2009 and reprinted by Chelsea Station Editions in 2012.