illustration by Jameson Currier

WIND

by Jameson Currier

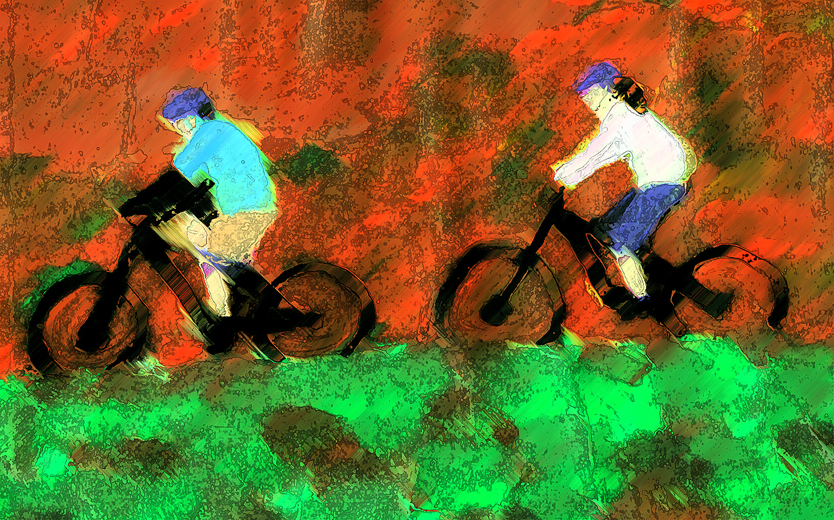

She had tried to convince him to take the day off. The training was starting to get to her — she wasn’t as obsessive about it as he was — and the drop in temperature had aggravated the muscles of her knees. Now, with all this constant exercise, she is worried that she is developing tendonitis. Jerold had agreed that they could skip the Deer Mountain run today. She is relieved not to have to try to navigate the highway, watch out for trucks. But at three he said he still wanted to go out somewhere: Why don’t they do a smaller loop from campus out to Upper White Chapel and the Fancy Gap Trail?

It is more than ninety minutes later before they set out. (He had taken a call from one of his students who asked if he knew if there was an English translation of one of the German texts listed on the course syllabus. Then she made him wait while she stretched her leg muscles and wrapped her knee.) She has on her tights today, the first time she has put them on since May. He wears khaki shorts over knee-length spandex briefs and a short-sleeve coolmax shirt. She has a long sleeve shirt and a wind shell on (which comes off almost as soon as they head out of campus).

She isn’t as fond of mountain biking as he is. She would have much rather gone cycling on a paved surface and at a slower pace. But most of the trails on the west side of town are not paved — more for horse riding than cycling. Helmets and padding are as essential as a water bottle. She never enters the competitions — she leaves that to him to do alone — which is what these daily excursions are all about. Or so he says: “I have to get ready for the 10K” or “I have to be able to do the two-part mountain run.”

The knee stills bothers her as they take Clifton Road down to the Old Union Highway so that they can cross the river at Bridge Street. She hates holding Jerold back on these rides. She always feels like she’s holding him back, even when her leg is functioning perfectly. But he’s always trying to show off by racing ahead of her, letting her know who has the strength. The truth is, he’ll peter out soon enough, slow down because he’s a fifty year-old man pretending he’s still a teenager. But she does not try to rob him of the pleasure these runs give him. And he seldom rides without her, says he prefers her company more than Professor Bosewell, the chemistry professor who sometimes fills in when she’s decided she’s really had enough of it.

They walk the bikes across the old one-lane bridge, the river gray, shivery waves catching the sunlight. They bike beneath the highway underpass, turning onto the old dirt trail that leads to the Upper White Chapel. To the west, suburbs roll over hills resembling seashore dunes. She looks at the new homes being built at the edge of the big meadows here: huge five and six-bedroom houses. She thinks they are too large, out of place for this small town. Houses which have video rooms and saunas which few in this town can afford. An easy ticket to bankruptcy. Unless they’re bought by the bureaucrats fleeing Capitol Hill, thinking they belong here.

The Fancy Gap Trail starts not far after that — a small climb up a hill that flattens for a space as it begins to circle Skyline Mountain. It follows an old deer fence along a stretch of farm land. As the elevation rises toward the chapel three kinds of weather can be seen at once — dark bellied clouds against the eastern mountain range, visible at the end of the horizon, clear sky above her head and to the north, and the white clusters of cumulus that travel inland, hanging over the valley on the east, sun breaking through in beams to shine against the University dorms. The wind is now harder up here — the chill works its way into her hands.

She has only done this loop maybe twice before. (He prefers the longer, tougher terrains.) But this trail is rougher than Deer Mountain — and the going is slower than she remembers. She has to constantly look at the road ahead of her, judging the rocks and holes and sticks in her path. She has to fight to keep the handlebars steady.

The deeper they ride the trail the nastier she finds the weather — the wind is brisk now, the sky lost. He rides well ahead of her. She keeps her pace steady as the elevation climbs. When she takes the decline of a small hill, she thinks she feels a drop of rain. She tries to look up, but can’t. She has broken a sweat, her concentration focused so intently on not falling off the bike.

He finds an easy path, bolts far ahead of her as the trail circles the cemetery that stretches behind the chapel. She imagines he will slow down soon. She will catch up with him when they reach the downhill terrain on the other side of the church. (He has a blister on the instep of his left foot that has been bothering him for three days. She knows he has difficulty taking the uphill paths.)

She is about a thousand feet behind him now. She sees him pump up a small dune, start down the other side when the bike slides away beneath him. A crow, which must have been sitting on the fence, flies up, swoops to a telephone pole on the other side of the trail. She thinks the pebbles must have scattered beneath the weight of Jerold’s wheels sending him off balance. She looks up quickly, trying to tell if he is hurt. All she sees is him standing, brushing the dust off his legs.

His eyes follow the bird first. He notices the scarecrow, thinks it’s doing a poor job of scaring the crow away. His own fall did much better. He stands, brushes his legs, looks off at the big meadow filled with tombstones behind the chapel. His next thought is that it is an odd place to hang a scarecrow — what is he guarding? — lost souls? It must be something children in one of the new houses put together. Halloween’s at the end of the month. He’s just about to yell over his shoulder to Jill to look at the scarecrow that some kids put together, when something — a flap of a shirt — catches his eyes. He thinks they did a good job with the hair. It actually looks real — the color of straw. Long and loose — like it had once been on a doll.

Then he notices the dark, rusty patches on the shirt, the russet-colored face. And then the features — the broken nose, the blistered mouth. They swim up to him, behind the color. He turns and waves Jill to stop.

“Turn around and go call the police,” he says, when she comes to stop beside him.

She is about to ask why when she sees a figure behind his shoulder, a scarecrow tied to the old deer fence.

He steps in front of her line of sight, to purposely block her view. “Try the chapel. Tell the preacher there’s a body out here. Tell them we’ve found a body.”

She turns the bike around without trying to look around him, but the image of the scarecrow has been burned into her mind. She tries to deconstruct it as she pedals faster. It all comes vividly back to her — a little boy — the hair, the shirt, the bruises, the blood.

She feels an urgency with every pedal. Pain from her knee shoots up into her thigh. She takes a path that cuts behind the fence. Seconds seem like hours. She feels like she is moving into warp speed while everything around her slows down. Time passes in images: the rut in the trail, the pothole before the paved street, the dark color of the cement, the clear windows of the chapel, the red front door. She leaves her bike in the driveway, runs to the door, trying to calm herself. She tries the door but it is locked. She looks around, runs to the side of the chapel and to another door. This door is locked too. But she sees a doorbell. She pushes a buzzer and waits.

A man answers that she recognizes — the preacher who oversees weddings at the chapel. Her words tumble out. She tries to keep them coherent — a body, a boy, beaten, tied to the old deer fence along the trail just at the end of the cemetery. Can she call the police and report it?

He nods his head, of course, waves her into the back rooms, his hand coming momentarily against the small of her back. He leads her this way through a room of steel office furniture into another where there ceiling expands into dark A-framed beams. He pulls a portable phone off its cradle, dials 9-1-1, hands her the phone. When a voice comes through she finds it hard to make her voice and thoughts connect. She hands the preacher back the phone. She is breathless. He says, “Hello?” into the receiver for her. After a pause he says, “I’d like to report an accident. We’ve found someone out on one of the trails. A body. A boy.”

She waits while he listens. Moments drag. She finds herself focusing on the pores of his skin, the size of his earlobe, a small black hair protruding from his nose.

When he pulls the receiver away from his ear, asks, “Was he still breathing? Do you know if he was alive?” the images of the boy again topple through her mind. For a moment she thinks she has fainted — everything has blacked out in front of her except the slow motion of the wind lifting the edges of the blue shirt. “Yes,” she answers, not knowing if her answer is the truth. “Yes,” she repeats. “I think I saw him breathing.”

* * *

They stayed until there was no reason to stay. He kept her distracted while they waited for the police to arrive, telling her there was nothing they should do, her knee throbbing with pain and trying to ignore it because it was so much less than what was happening before her. He had spoken to the boy while she was away calling for help, saying a few optimistic words to him like, “We’re getting help for you.” and “We’ll get a doctor here and everything will be fine. Just stay with me, okay?”

He had thought about cutting the boy down from the fence post, but he didn’t have a knife, could think of nothing to use but his hands to untie the rope. He held himself back because he knew this was a crime, that he mustn’t confuse any of the evidence he had already walked into, and it was best to wait for someone who knew what they were doing — what if the boy was still alive and the way he had moved him had made him die? He didn’t want to be responsible. It was only an accident that they had discovered him at all. He pressed his fingertips against the neck of the boy, hoping to find a pulse, but he could feel nothing because the cold had numbed his fingers. He wiped the blood, still freshly dripping out of boy’s ear, onto his shorts. The body was small, or looked to be small in the way it had been tied to the fence. The wrists were swollen. Blood had dried on the boy’s face, streaks erasing the rusty color where there appeared to have been tears. The hair was matted with more dried blood. One eye was a blackish-blue bruise, the other eyelid closed, lifeless. The nose was broken, the edges of the lips bloody and bruised. There was no movement to the body except the wind blowing through the clothes. He thought certain the boy was dead or if he wasn’t, he would certainly not survive even with help on the way. Who could have done such a thing? He said more words to the boy. “They’re coming. Just hold on. We have someone coming to help you out.”

The officer found them standing beside their bikes — her complexion red, her eyes wide, the parka knotted around her waist. Jerold still had his helmet on. His hands were on his hips, as if he was impatient, his shorts soiled with rusty brown smears. The minister was at the fence now, kneeling on his knees in the dusty trail, reciting words to the boy, or perhaps just what remained of his body. It was 6:04 when the squad car arrived. She remembers this because she looked down at her watch. The light was still with them then, but the sky had grown overcast, the ridge of mountains a faint blue haze. The wind continued, unabated, at about ten miles per hour, blowing down the slope from the chapel and across the cemetery. She felt the chill work its way deeper into her skin and she untied the parka from her waist and put it on.

She drew her face against Jerold’s chest. Jerold watched the officer approach the minister and the body of the boy. The minister stood, took a few steps back, and the face of the boy swam up into view again: the swollen eye, the streaks of tears through the blood, the misshapened mouth. He watched the officer use a boot knife to cut the body free from the fence, using his shoulder to hold the boy in place and unfold his legs and place him on the ground.

“Can I help?” she heard the minister ask, and she looked up, at the fence and where the boy was lying in the dust. She wondered what his mother would think, how she will react when she hears of her son found in this condition. She let her mind drift away from the boy to the time when she was four months pregnant and miscarried, then something the officer said drew her back to the scene.

“I got him,” the officer said. “It’s okay folks. I’ll get him comfortable. I need you to stay back from the area.”

An ambulance arrived, the body was examined, the stretcher wheeled out from the back of the van. The officer searched the ground near the fence, the dusty path; soon a flashlight was pulled off of his hip and he leaned in close to look at the pebbles and debris. By the time another officer reached them it was twilight, the van was leaving, red lights flashing, the siren held back until the ambulance reached the paved road. She let Jerold answer the questions because he was always better at this — he knew how to find order within chaos. His assurance was authoritative, removed them from any possible suspicion. He answered why they were biking, why this path, this day, this hour. She leaned her neck and ear against his chest, feeling the vibrations of his vocal chords and the movements of air in and out of his lungs. He asked the officers about the identity of the boy, what evidence they found, what they thought was going on in this neighborhood, who could have done this kind of crime. The officer told him exactly what he knew: nothing at this moment. When Jerold leaned his chin down and spoke directly to her, said that they are leaving the bikes behind and that the police would bring them by the house the following day, she moved away from him, as if awakening from a deep sleep. In the squad car that drove them home she closed her eyes and saw the wind blowing through the boy’s shirt. “Was he still alive?” she asked Jerold.

“Yes,” he answered. “But barely.”

* * *

She is working at the kitchen table when the first call arrives. It is not even eight o’clock. Neither of them have slept well through the night. Jerold was up working on line, uploading a syllabus to a Web page and e-mailing a colleague at the University hospital where the boy had been taken for updates on his condition. She had let her mind wander from one gruesome detail to the next — the swollen eye, the wrists tied behind the back, the blood wiped on Jerold’s shorts, until she decided she had needed to find a way to work through her anxiety and unrolled the yoga mat that had been stored in the closet since last summer and followed a videotape through relaxation movements. She practiced her breathing for an hour trying to calm down, then wandered outside onto the porch where she could feel the wind. This morning she decided she would stay home from work — it didn’t seem right to show up and talk about it with other people.

Jerold answers the phone in the small room he uses as his office while he is at home. She hears him clear his throat, answer the caller with, “Yes, this is he.” Ordinarily she would have had no desire to eavesdrop, to listen in on his conversation — they are usually too boring and too academic and at times she finds his tone a bit too arrogant for her liking — but this morning she knows instinctively the call is about the boy and she stops working at the kitchen table to listen to him.

“Yes, it is a shame,” he says to the caller. “He was in pretty bad shape.”

He fills the caller in with the details he has — they were out biking, spotted the boy tied to the fence. “It’s hard to imagine that type of violence around here,” he says. “I hope they find whomever did this and bring them to justice swiftly.”

She hears him give more details which he has not told her, details which he must have gotten through colleagues sometime during the night. “Yes, one side of his head was beaten in. Eighteen blows to the skull, the ribs cracked, and a chipped tooth found in his windpipe. It was disgusting the way he was roped to the fence. Like it was a sign or a warning for someone. His shoes were missing. Why would someone beat a young man like that and take his shoes? How could they even expect him to walk after that kind of beating?”

The fact about the shoes surprises her. She had not noticed he was without shoes. She had not been looking at the boy’s feet, or for his shoes — the way he had been pinned to the fence his legs had been bundled up beneath his body and when he had been untied and lain on the ground, she had not noticed his legs. She had been looking at his face whenever she could force herself to look — as if she could detect who he was and why he was here, tied to a fence on a windy slope of a mountain of all places.

Next, Jerold unravels motives as if he is an expert. This surprises her even more, that he has given what has happened such deep thought, or different, deeper thoughts than she has been able to swim through. “I hardly think self defense explains the crime,” Jerold says. “The young man was so small we thought he was a young boy. I suppose it was a robbery that went bad. Or perhaps a drug sale — though I understand that the police did not find any money or drugs at the crime scene. It’s shocking that they believe he had been out there for such a long time. Eighteen hours before we found him. It’s a miracle that he is still alive.”

Eighteen hours. She had not known that fact either. Eighteen hours tied to a fence, unconscious, bleeding, the body absorbing and accommodating pain. What is going on here? Why would anyone do this? She feels her body tensing, again summoning up the image of the boy on the dusty trail. There it is, she sees — there he is, lying in the dirt, without socks or shoes: his feet are bare.

“I understand the police have identified the boy, but they are not releasing his name until his parents can be contacted,” Jerold says. “But they are releasing some information. He’s a student at the University. First year. A transfer student from Denver.”

A college student? She thinks he was too young to be in college. He looked no older than thirteen to her. Now she finds the boy’s face again — the bloated, swelling bruises, the long bangs of hair. He was that old? A college boy? No, it isn’t possible. He hardly looked old enough to wander away from home. She wonders again how his mother will react to the news and she rises slowly from her chair, as if standing she can hear Jerold’s voice better.

“No, he was not in any of my classes,” he answers. “He was not one of my students.”

She hears him thank the caller and hang up the phone. She waits for him to walk down the hall and tell her the details he knows. She looks down at the notes of the report she has been working on at the table. When Jerold makes no movement to find her, she leaves the kitchen and walks to his room.

“You heard?” he asks her. He has not moved from when he hung up the phone. “It was a reporter from the campus radio station. He says that the police have a suspect in custody and are searching for another guy.” Jerold tells her that an abandoned truck has been found. A gun has been recovered: a 357 Magnum, blood covering the casing, the barrel, and the butt. Apparently it was used to beat the boy. “Who would do some kind of sick thing like that?” he asks her.

“It’s none of our concern,” she answers. “This should not be in our hands.”

* * *

He continues to take calls. At home. At his office on campus. He uses his class time to announce the crime to his students: a young man has been found beaten, if anyone has any information they should contact the police. He talks with a few students after class and suggests his theory: a drug sale or robbery gone bad. This is what can happen when things go too far, he tells them. Let this be a warning that accidents like this could happen to you, too.

By the afternoon, he has canceled his office hours and agreed to meet a television reporter on the trail near the fence where the young man was found. By now the young man’s parents have been located, the identity of the student released to the local press. He is Daniel Saylor, twenty-one years old, a transfer student from Denver; his mother and father in Virginia are on their way to the University and the hospital. The suspect in question is a local boy — a nineteen year-old drop-out named T.J. McConnell. When Jerold meets the reporter and a cameraman on the trail he talks about mountain biking and where the best trails in the area can be found. He describes the time he invests in the sport, the amount of training required every week, and the fact that he skipped his usual practice today because, well, somehow it just didn’t seem right to do it after what has happened. The reporter is a tall, slender young fellow, his black wavy hair unmoving in the wind; he shifts the conversation while looking down at his notepad — “You think this has something to do with drugs?” he asks Jerold.

Jerold explains his growing theory, the animosity between the locals and the academics, the fact that it must have reached a boiling point in this instance. “It’s a bit of a confrontation sometimes,” he says off-camera. Before filming begins, he makes sure the reporter has the correct spelling of his last name, his position and department at the University.

They place him so that the fence is behind him. The slope and the chapel blur in the corner of the frame, not overwhelmingly present but still noticeable and distinct. If the cameraman were to change focus, sharpen the background instead of on the foreground, the cemetery would come into view, the tops of tombstones could be seen before the grassy hill plunges down to the trail.

On the trail, Jerold has to shift his balance to keep his weight from resting on the blister of his foot. “I find it hard to think that there could be such hatred in this town,” he says when filming begins. “This town has a history of tolerance. It offends me to think that someone from our town could do something like this.”

When Jill sees the broadcast on television she is appalled to find him talking about this. Our town? Why has he turned himself into a spokesman for the town? Why is he not talking about how they found the boy? About biking that day to Fancy Gap? Why has he stopped talking about what he knows and loves — biking on the mountain trails — and the fact that it was merely accidental that they found the boy at all? Jerold is a transplant from Boston academia — he’s only here because it was the best of the three schools which offered him a teaching position after he ran into some trouble over unaccredited sources in a paper he published. He has lived here less than five years, and every year he talks about applying to a better position or joining a bigger department at a higher-rated school that is “not so out in the boondocks in a hicktown place like this.” He hates this place. He says it is culturally-deprived, narrow-minded, and behind the times. He complains that his department does not even have a working color printer, or a photocopy machine that can staple collated copies.

“This is a beautiful, secluded town and the majority of the people here are hardworking, good people,” Jerold says. “But there is a sense that University community is one of outsiders, not locals.” He carefully explains the differences between the local youths who drop out of high school, get into drugs and work in service jobs — as pump jockeys at gas stations, as waitresses at the town restaurants, as clerks and bag boys at grocery story — and their growing resentment toward the bright, upscale students from suburban families who arrive to attend the University with money in their pockets to burn. “But this kind of violence?” he says. “I find it hard to believe that it could happen here.”

Here? Here? What does he understand of here? She resents his implication that the University is for outsiders. She worked as a waitress to pay her way through the University. She was born in the old wing of the hospital where the young man now lies struggling to stay alive. Her mother had cleaned motel rooms; her father had kept up several jobs, including an early morning delivery route for a dairy and sorting garbage at the recycling center, where he still works. Her family had been here as long as the town had been here — her great-grandfather had worked on farmland in the northern part of the county.

As more news unfolds, however, her anger shifts and is displaced by disbelief. Jerold is no longer talking and the reporter says that the young man was last spotted at a local tavern, the Starlite Bar and Grill, where a bartender has identified him as a customer the night he is believed to have been assaulted. A photo of the young man is shown. She stares at it and only recognizes the long bangs of blond hair — the blue eyes, the slender nose, the half-knowing smile is one which belongs to a stranger, not the child — yes, the child — they discovered tied to a fence.

Unconscious, fracture of the skull, struggling to survive, waiting for parents to arrive: the rest of the report goes by in a blur. When Jerold calls her after the broadcast, he tells her not to expect him home early. There is another reporter and another interview and more news that is breaking about the case. “They’ve started interviewing some of his friends,” Jerold says. “And some students have started talking to the police. I just heard that the boy was gay. This changes everything. This could blow apart my theory.”

* * *

Driving across town to her parents’ house, she is surprised to find Jerold again on the radio. He is talking to a student reporter on the University radio station, saying, “Well, yes, it must be difficult to be a gay man or a lesbian in this town. There are no gay bars here, no support groups — the campus gay and lesbian organization disbanded about four years ago because the members were frightened of harassment and discrimination.”

His composure surprises her. Usually the topic of homosexuality agitates him, makes his voice go high and his words come out in a whispery rush. In private he complains about the married, closeted-gay professor in his department who is two decades younger than he is and certain to be tenured because the department chairman is also married and closeted himself. She thinks he is doing this to look good to them, to prove that he is liberal and tolerant and a wise choice to become tenured himself.

A phone caller is next, a woman with a twangy sort of accent who begins to speak about the rednecks who hang out at the Starlite Bar and Grill, where the boy is presumed to have met his assailants. “I’m surprised that he went looking there of all places,” she says. “The guys who hang out there are nothing but jerks.”

Jerold begins talking about homosexuality again and the few choices that are available to single gay men in this town looking for partners, sexual or otherwise. He explains that sodomy is illegal in this state, and that by admitting you are gay you are in effect admitting to serious criminal behavior. He explains that gay activity has always been underground in this town and at the University, but was forced further underground during the late 1980s when the AIDS hysteria was at its worst across the nation and the adult bookstore on the edges of town was closed. This was also when the state set up a sting operation in which six men were arrested in Jackson Park, the triangle of grass and shrubs that’s opposite the old Opera House on South Main. “They weren’t arrested for having sex with an undercover cop,” Jerold says. “The six men were charged with soliciting a felony, which in this state is itself a felony. One of the students was expelled and the danger of being thrown out of town has created an oral history within the University gay community. One of my gay students said he heard all about this his first week of classes from another, older gay student. I don’t know what the police have uncovered as the motive for this kind of violent beating, but it seems certain to me that the young man’s sexuality played some kind of factor in it.”

At her parents’ house she finds her mother in the kitchen. They have finished eating supper and her mother is rinsing dishes and slipping them into the dishwasher. Her mother says, “What a shame for this to happen to anyone’s child. Have you heard anything about the boy’s mother?”

She shakes her head, “no,” and her mother mentions that she thinks the young man could be the grandson of the Saylors that used to live two towns over. “The ones who sold us the washing machine that year when ours kept breaking down and we couldn’t get a repairman out here,” her mother says. “They were having rough times, too, as I recall. They had a son who married and moved away. It could be him. His boy could have decided to go to school where his daddy’s roots were deep — where his family is from. Makes sense to me. Otherwise, why would such a smart city boy like that want to come here of all places?”

She doesn’t answer her mother and looks in the refrigerator. She avoids eating any of her mother’s leftovers. She opens a cabinet and picks at a bag of opened potato chips before she finally settles down at the kitchen table with a bowl of ice cream. She tells her mother how her knee is bothering her, probably because she over-exercises by going out on the bike rides with Jerold. Her mother tells her to soak her knee in Epsom salts, but doesn’t ask about Jerold’s whereabouts or how he is coping through these events. Jerold is not one of her mother’s favorites of the men she has dated or lived with; she thinks he is too old for Jill and conceited, more eager to display his intelligence than his wisdom or common sense, and she is just waiting for the day that they will call it quits and finally break up. She never approved of the way they met: he was Jill’s professor his first year at the University.

She tells her mother a few things about finding the boy, things she has not told her over the phone. Before she leaves, she finds her father in the garage working on the door hinge on the side of his truck. She says a few words about the boy and that she doesn’t believe he will survive much longer. He asks if she went to the hospital or talked to his parents.

“No,” she says. “I think we should stay out of it, don’t you?”

“I suppose it wouldn’t hurt to say a few prayers for him,” he says. “No one deserves to die that way. It’s a shame these kids have to try so many drugs today.”

“They aren’t saying it was drugs anymore,” she answers. “Jerold was just on the radio talking about how this guy was beat up because he was a homosexual.”

“What does Jerold know about this?” her father asks.

“Nothing, really, except that he’s caught up in the middle of it all,” she says. “He started talking about the town and then he started talking about gay people because some of his students are gay.”

“I suppose some people just like to talk,” he says.

She knows her father will not come out and outwardly express his dislike of Jerold; that is not his way, not what he has taught her to do either, which is why she understands that she cannot and will not confront Jerold on his recent outspoken behavior.

On her way home, more details about the crime have been revealed and she switches between radio stations to listen to the reports. The second suspect has been arrested. Daniel Saylors’ parents have arrived at the hospital. The hospital has released a statement on the boy’s condition: Daniel is unconscious and on breathing support and his temperature has fluctuated between ninety-eight and one hundred and six degrees. “Daniel’s parents would like to thank everyone for their kind thoughts about Danny and their fond wishes for his speedy recovery,” the announcer reads. “The family appreciates all the prayers and the good will that have been sent to them because of Danny and strongly request that their privacy be respected during this difficult time.”

On the last mile toward the house, the route she took the night they came back from the Fancy Gap Trail in the police car, the boy’s beaten face swims up in her memory — the busted lip, the swollen eye, the streaks of tears through the dried blood. She wishes she could escape the image, just drive around it, but it is there, haunting her until she parks the car and goes inside the house.

When Jerold shows up later he asks her if she saw the late news broadcast. She nods but she won’t meet his eyes, won’t show him what he wants, that she is proud of him for what he is doing because she is not.

“No one else would go on camera and talk about it,” he says, as if he is reading her mind.

She tries to tell him that he should question his own motives, but it seems the wrong moment and she closes in on herself, fells her interior castle caving in, the walls tumbling down as if a hurricane is rushing around inside her.

“I heard the two local guys beat him up because the boy made advances toward them,” Jerold says. “That’s the story the lawyers are putting out now. They call it a ‘gay panic’ response.”

“And you believe that?” she asks. “After what you just said on TV? How hard it is for a gay man to be out and open in this town?”

He frowns at her, meets her stare as if he can see the wind rushing around inside of her eyes, waiting to come out with a stronger attack. “I’m not the villain here,” he says. “Remember that. I’m not the one who beat him up.”

* * *

The next morning she is working at the kitchen table when the police car arrives. This officer is short and wide and looks like he could bench press more than two hundred pounds. He wears a white shirt, leather jacket, and a dark tie. He walks across the leafy landscape in serious strides, his bald scalp catching the light.

“Professor,” the officer says when Jerold comes the door. “You don’t mind if I ask you and your wife a few more questions.”

“You want some coffee?” she asks.

“I already had three cups today,” the officer answers. “Too much for me, ya know?”

“I hear you,” she answers and smiles, the first time in days, she thinks, that she has moved her lips into that position.

She sits on the sofa. Jerold continues to stand. The house seems barren, as if something is missing; she notices a daddy-long legs crawling in the corner of the carpeted floor. “It’s about the boy, isn’t it?” she asks.

“It is,” the officer answers.

The light from outside bends into the room. The wind blows through a tree, causing the yellow undersides of leaves to change the pattern on the floor. “You think he’s gonna live?” Jerold asks.

“They don’t expect it,” the officer answers.

“We were very thorough with the responding officer,” Jerold says. He is tense, as if he is expecting a problem.

“It’s about the boy,” the officer answers. He hesitates. His skin changes color, thickens, reddens. There is a light sweat at his lip as he loses his confidence. “The hospital ran some tests. They found the young man was HIV-positive. He has the virus that causes AIDS.”

Jerold does not respond. At first he is blinded. This news is not expected. Not at all. Blood rushes swiftly inside him, creating blackness, then panic. He sees things being taken away from him: his job, his house, his income, his health.

“Did either of you touch his body?” the officer asks. “Did you happen to try to help him?”

“Yes,” Jerold answers. “Of course.” He turns to Jill, looks at her and sees that she has lost her color. “While she was calling for help at the church, I tried to help him. I used my hand — my fingers — to touch his neck, to see if I could find a pulse. There was blood dripping from his ear.”

The scene replays in his mind. His hands reaching out to touch the boy’s hair, pulling up his chin to look at his eyes — he had forgotten that, forgotten those moments because of the blood when he felt for the pulse.

“Were you wearing gloves?” the officer asks.

Jerold feels naked, exposed. His eyes tear; he folds his arms across his chest. He has put himself on the line without knowing it, by only trying to help someone. Why has this happened? Why is this happening to me?

“Professor?”

“No,” he answers. “Of course not.”

His tone makes her look at him. She can tell he is not only frightened, but angered as well. She knows he is bitterly thinking that he is paying the price for everyone else’s problems in this matter: the town, the University, the locals versus the academics, the underground world of closeted gay men.

“The hospital is suggesting that anyone who might have been exposed to the blood be set up on a cycle of medication,” the officer says. “It’s best if it is started during the first thirty-six hours after exposure.”

“Who else knows this?” he asks.

“No one,” the officer answers. “It won’t be part of the report.”

Their positions change as if this has been rehearsed before. He slowly sits and she stands, writes the name of the doctor on a slip of paper, and sees the officer outside the door. By the time she has returned to him, he has buried his head into his hands. She waits while he works his way through the frustration, while the crying jag comes and goes, then she brings water and says she will drive him to the hospital.

* * *

After they return from the hospital he naps on the sofa. He sleeps through the rest of the morning, misses lunch. She answers the phone calls, says he is not available to talk to any reporters. In the kitchen she listens to the radio while she works at the table, breaking her concentration as new reports give continuing updates and comments on the unfolding case of the beaten gay boy. She hears Jerold get up from the couch, walk through the back room on the creaking floor boards, hears the water begin to flow through the pipes as he turns the shower faucets on, the hot water pipe trembling in the shell of the wall as the water heater in the basement begins to heat up. She becomes lost in her project again, then lost in a report, and when the phone rings again she waits to see if he will answer it and when she realizes he won’t, she crosses the kitchen floor to the phone on the wall.

The news surprises her. Even with all the continuing developments — the arraignment, the television cameramen and reporters descending on the town, the students creating an impromptu candlelight vigil the night before, she is unprepared for the news. She did not expect it to arrive now. Jerold’s colleague at the hospital is phoning to tell him that the boy has died. About twenty minutes ago. It won’t be released to the press for some time in order for the parents to prepare a statement. She thanks him for calling and says she will pass on the news.

She sits down at the table. The storm that has brewed in her chest for days has now reached her head. She fights back tears, fights a little harder and walks into the living room where he Jerold is back on the sofa.

He is not sleeping any more. His hair is wet and he has changed clothes. When she enters the room, he lifts his eyes and they meet hers. He knows without speaking why she is there and she stands for a long while wanting to be comforted but he does not have the strength to do it for her.

“I thought I would bike out to Fancy Gap,” she finally says. “Pay my respects.”

She leaves the room and begins to find the things she will need for the ride: her helmet, the wind shell, a rubberband to hold her hair behind her neck. She wraps her knee with a bandage and fills her water bottle up at the sink. While she is out in the garage, peeling off a label from the bike frame where the police wrote her name and address, he finds her and says, “I’ll come with you. I need to get out of here for a while.”

She takes the lead when they set out from the house. He feels drained, hoping the exercise will make him feel stronger, make him want to stay alive. They bike down Clifton Road, continue around the media vans now parked on Bridge Street, and walk their bikes across the river bridge. The wind is blowing harder today, but at the moment it is surprisingly warm air. Where the Fancy Gap Trail starts the air grows colder and by the time the deer fence has come into view her fingers are numb; his ears are burning — he feels his blood rushing through his body.

She rides well ahead of him today, turning around to make sure he is all right, that nothing has happened, that he hasn’t decided to give up and turn around. She keeps her pace slow and easy as the elevation climbs, thinking at moments it might be easier to walk than to ride over the pebbly path. As they approach the site she notices the cars parked on the side of the path: two small cars, a red sports car and a silver Ford, are side by side; an old Chevy juts out along the trail; behind it sits a white media van with a satellite antenna on the roof. There is a small crowd standing where the section of the fence has been removed by the police for evidence. When she parks her bike and knocks the kickstand down, she sees a crow fly over head. She waits at her bike until Jerold is beside her and they approach the fence together.

Visitors have created a makeshift memorial. Bundles of flowers have been tossed on the ground where the boy’s legs were folded beneath his body. Someone has nailed a cross to the fence; someone else has placed a picture of the boy as it appeared in the newspaper in a small frame and leaned it beside the flowers.

The wind is harder today. The flowers on the ground tremble. She kneels in the dirt to shield herself, to find a little more warmth, clasping the ends of her parka together with her hands shoved into the pockets. Jerold stands behind her, still thinking of his fingers reaching out to find the boy’s pulse.

On the path, a reporter is interviewing a small group of students — they must be students, she thinks as she looks back at them, because they are young and dressed in jeans and tight jackets covered with ribbons and buttons with printed slogans. One of the girls recognizes Jerold, says something to the reporter, and within moments the student has approached Jerold and asked if he has heard the news. Of course the girl has not heard of the other news, the news that is not being reported and which has now blown Jerold further apart from Jill. The reporter — a young blond woman in an uncomfortable-looking blue business suit, not much older than the students, approaches Jerold and asks him if he will comment on the boy’s death for her news report — it would be broadcast from the fence. A live broadcast. Jerold stares at the reporter a bit too hard, does not answer her, and when Jill sees he has become trapped again in the horror of his own current events, she stands and says that she would be glad to talk about how they found the boy that afternoon. She was there, too — she was the one who went to call for help.

The cameraman makes them change positions several times because of the wind. Soon they are away from the fence and she is standing alone in the spot where she stayed while she waited for the police to arrive. She doesn’t mention this to the reporter or the cameraman. For a moment she becomes lost in her own images — the russet-colored face, the broken nose, the blistered mouth. She waits for the signal from the reporter to begin speaking, but all she can hear is the wind in her ears. She looks at Jerold, standing at the fence, looking back at her. They seem so far apart even though they see the same thing. She sees the wind, too, lifting the edges of the blood-stained shirt. “I saw him breathing,” she begins. “I saw him while he was still alive.”

________

“Wind” is an extract from an early draft of A Gathering Storm, a novel by Jameson Currier.

A Gathering Storm by Jameson Currier was published in 2014 and was a Lambda Literary finalist in Gay Mystery.